My high school chorale was rehearsing the terrific William Dawson arrangement of the spiritual, “Soon Ah Will Be Done,” when the director, trying to get us to sink into the harmonies at the end of each phrase, many of which were on the word, “God,” said “God is a groove.”

I immediately wrote the following on the front of my choir folder: “‘God is a groove.’ ~ John Sternisha.” In the interest of fairness, my friend and folder-mate (now a professor at the University of California – Berkely; make of that what you will), wrote the following right underneath: “‘God is dead.’ ~ Friedrich Nietzsche.”

I’m still in camp “God is a groove,” but we won’t settle that debate today. However, I will use the God debate as a jumping-off point to consider the nature and relevance of evidence for determining what is true and how we ought to live our lives.

If you’re new here, check out these TBL “greatest hits” below.

If you like The Better Letter, please subscribe, share it, and forward it widely.

NOTE: Some email services may truncate TBL. If so, or if you’d prefer, you can read it all here. If it is clipped, you can also click on “View entire message” and you’ll be able to view the entire post in your email app.

Thanks for visiting.

The Necessary Leap

Well before the turn of the century, when the internet was still a novelty, I spent an untoward amount of time on atheist websites and discussion boards. They were surprisingly redundant and repetitive,1 as there are only so many ways one can invoke Ockham’s Razor, proclaim the need for rationality, accuse others with logical fallacies, and advocate for what Richard Dawkins now calls the “Evidence-based Life.” Those of us who believe in God were deemed, necessarily and predictably, to be stupid, evil, or mentally ill. Perhaps all three.

It seemed that every internet atheist would quote W.K. Clifford’s The Ethics of Belief at every opportunity: “it is wrong always, everywhere, and for anyone, to believe anything upon insufficient evidence.”2

Let’s be clear from the get-go. Evidence-based thinking is a terrific thing – a crucial thing even. But it is also inherently limited.

Each of us (and every ideology – good, bad, indifferent, benign, effective, evil, etc.) necessarily rests his or her core beliefs (or humanity, if you will) on certain ideas that we must take as given since they cannot in principle be evidence-based. Examples include such statements as all men are created equal, I should marry her, representative government is good, Bach’s music is beautiful, political equality is a fundamental right, ice cream tastes great (I especially like Moose Tracks), we should help the weak, stealing is wrong, love is the most important thing, and it is wrong always, everywhere, and for anyone, to believe anything upon insufficient evidence.3

Not coincidentally, these ideas relate to the most significant and interesting areas of our existence – meaning, value, virtue, beauty, desire, and worth (cf. John Stuart Mill’s “moral sciences”). Indeed, these foundational principles relate to what we, in our better moments, think of as human attributes, as opposed to those of mere meat machines. Put another way, there are a significant number of things we existentially need to know about which empirical evidence has precious little to say.

As William James argued in The Varieties of Religious Experience: “We and God have business with each other; and in opening ourselves to his influence our deepest destiny is fulfilled.” Would-be rationalists are left to rely upon Pontius Pilate (“What is truth?”) or, more nearly, Alfred E. Newman (“What – me worry?”). Despite Clifford’s claim, we all, of necessity, build our lives and our most important beliefs on unevidenced assumptions.

But wait, there’s more.

When America’s Founders revolted against British rule in 1776, they were risking execution for treason by challenging the greatest power the then-world had ever known. Nobody following the evidence and the probabilities alone would undertake such a thing.

About 90 percent of start-up businesses go belly-up.4 Nobody following the evidence and the probabilities alone would start one.

Most relationships fail. Even highly successful relationships fail as more than half of marriages end in divorce. Nobody following the evidence and the probabilities alone would start a relationship.

However.

Morgan Housel makes a world-altering point (emphasis in original).

“Long tails [highly unlikely, perhaps unexpected events] drive everything. They dominate business, investing, sports, politics, products, careers, everything. Rule of thumb: Anything that is huge, profitable, famous, or influential is the result of a tail event.”

Following the evidence and the probabilities alone wouldn’t allow us to dream, to run for president, to go for the gold, to take the last shot, to go out on her own, to create the next big thing, to go all-in, to storm the beachhead, and to demand (or expect) true love.

As I have written before, our world is increasingly characterized by an “index mindset.” The idea comes from the success of index investing, whereby investors eschew active management of their portfolios (searching for big winners) to own an entire index of stocks, providing a mechanism for decent returns while (mostly) not losing big.

The index mindset tries to follow the evidence and act probabilistically. Very broadly speaking, it favors average results over extreme ones, a bird-in-hand over two in the bush, relative over particular truth, function over form, quantity over quality, mandate over merit, efficiency over exploration, passivity over action, predictability over tails, determinism over freedom of choice, mistake avoidance over smart decisions, evolution over revolution, adaptation over reformation, safety over risk, diversification over concentration, preservation over creation, velocity over due diligence, optionality over decisiveness, the general over the specific, and growth over profit.

This approach is often an appropriate default – as with investment in public markets, where it works very well. In other contexts, it is usually pedestrian and often dangerous.

The index mindset is about risk mitigation rather than ambition. It is about management and administration rather than opportunity. It is about the efficient frontier rather than the bleeding edge. It is about scale and cost efficiency rather than uniqueness and quality. Following the evidence is all evolution and incrementalism but no disruption and no revolution.

To be sure, the risks of stepping out of the index mindset are both real and substantial. The world, as ever, is increasingly complex and often wildly random. Our abilities are limited. Our analysis is flawed. Our judgments are highly imperfect. Our priorities are at cross-purposes. Or wrong. We are human, for good and for ill.

As I say in my day job, returns needn’t turn up when you want or need them. They may not turn up at all. And we lust after certainty in a highly uncertain world.

So how should we decide?

In his Pensées, seventeenth-century French mathematician, philosopher, physicist, and theologian Blaise Pascal offered what has come to be known as Pascal’s Wager. He posited that God either exists or does not and that we may choose to believe in Him or not. If one believes in the Christian God and this God exists, he gains infinite happiness; if one does not believe in the Christian God and God exists, he receives infinite suffering. On the other hand, if one believes in the Christian God and He does not exist, he suffers some finite disadvantages from a life of Christian living; and if one does not believe in this God and He does not exist, he receives some finite pleasure from a life lived unhindered by Christianity.

“Let us weigh the gain and the loss in wagering that God is. Let us estimate these two chances. If you gain, you gain all; if you lose, you lose nothing. Wager, then, without hesitation that He is.”

Because there are other possibilities, the Wager isn’t nearly as good an argument for God as many Christians assume. However, it rightly includes analyzing the stakes along with evidence and probability when making decisions. One might reasonably make a lower probability choice if the pay-off is good enough.

Big risk. Big reward.

For the really great, life-changing, world-altering stuff, optionality isn’t always a good thing.

My wife frequently counsels students thinking about teaching. Because the negatives are so high – limited pay, low recognition, difficult parents, etc. – she advises them to do it only if they can’t happily do anything else. It’s the Jeff Bezos regret minimization framework.

“I knew that when I was 80, I was not going to regret having tried this. I was not going to regret trying to participate in this thing called the internet that I thought was going to be a really big deal. I knew that if I failed, I wouldn’t regret that. But I knew the one thing I might regret is not ever having tried. I knew that that would haunt me every day.”

On one level, regret minimization doesn’t feel like going for it. However, in my experience, regret is more often a product of not doing something than of doing something that doesn’t turn out optimally. Or at all.

Internet atheists laugh at believers taking leaps of faith and insist we aren’t following the evidence. But almost nothing great happens without acting irrespective of the evidence.

It’s a necessary leap.

As Wayne Gretzky famously said, “You miss 100 percent of the shots you don’t take.”

So fire away.

Totally Worth It

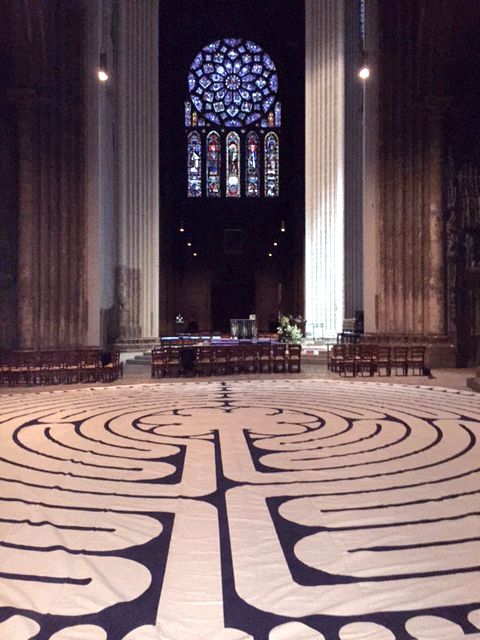

In his Universe of Stone: Chartres Cathedral and the Triumph of the Medieval Mind, Philip Ball argues that the Chartres Cathedral represents a shift in the way western Christianity thought about God, the universe and our role in it. What had once been dark and inward-looking became a celebration of the light of reason and the movement from an age when God could only be feared to one where his works could be understood. Indeed, if you sit in the cathedral late in the day, one can believe that the place embodies the idea that a reconciliation of faith and reason is not only possible, but inevitable. The famous labyrinth on the floor of the Cathedral’s nave has never been adequately explained. But it is not truly a labyrinth. There are no possible wrong turns – all roads lead inexorably to the center.

Feel free to contact me via rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or on Twitter (@rpseawright) and let me know what you like, what you don’t like, what you’d like to see changed, and what you’d add. Praise, condemnation, and feedback are always welcome.

Of course, the easiest way to share TBL is simply to forward it to a few dozen of your closest friends.

It’s commencement season and that means commencement speeches. I love them, even Scott Alexander’s terrific fake graduation speech. The most meaningful to me are, in no particular order, those from Kurt Vonnegut (my college graduation), Peter Kreeft, Anne Lamott (recorded as a TED Talk years later), Atul Gawande, Richard Feynman, Denzel Washington, William McRaven, Randy Pausch, Steve Jobs, Frederick Buechner, Fred Rogers, and David Foster Wallace. Be sure to catch the outstanding adaptation of Wallace’s speech below. It gets me every time.

The TBL playlist now includes more than 275 songs and about 20 hours of great music. I urge you to listen in, sing along, and turn up the volume.

Benediction

We live on “a hurtling planet,” the poet Rod Jellema informed us, “swung from a thread of light and saved by nothing but grace.” To those of us prone to wander, to those who are broken, to those who flee and fight in fear – which is every last lost one of us – there is a faith that offers grace and hope. And may love have the last word. Now and forever. Amen.

As always, thanks for reading.

Issue 174 (May 17, 2024)

Yes, it was intentional.

At the end of The God Delusion, Richard Dawkins explains how he would view a miraculous event – say, “[a] statue of a madonna...wav[ing] its hand at us.” In his view and in that instance, his philosophical assumptions would force him to conclude that no miracle had happened. Instead, “the jiggling atoms in the hand could all just happen to move in the same direction at the same time. And again. And again.... In this case the hand would move, and we’d see it waving at us” (id., emphasis in original). Accordingly, even though Dawkins pays lip service to the idea that evidence could and would change his mind, he has philosophically precluded the idea that such evidence in the form of the miraculous could possibly exist. His alleged commitment to the primacy of evidence is entirely domain dependent.

Some of our base-line assumptions may be falsified, but they cannot be evidenced.

And nearly 60 percent of U.S. stocks since 1926 reduced rather than increased shareholder wealth.

The moral of your story Bob is that the life of every single one of us is defined by our relationship with risk. I’d venture that most people don’t view it that way. They should read Nassim Taleb. And Sartre - so they’d know that their failure to appreciate and act upon their innate freedom by taking some risks is behaving in bad faith. And they' should you. BTW - it brought a yuge smile to my face that you could quote Morgan Housel AND Alfred E. Newman - meaningfully - within the flow of your argument. Not easy to do!

This was a wonderful piece.