Strong-Link Problems

The first of two parts on seeking a fat-tailed life.

I grew up in heartland America. It wasn’t the middle of nowhere, but you could see it from there. My parents were there first, of course.

My mother was born into a dysfunctional and abusive family during World War I.1 She graduated from high school early to escape but only to an abusive marriage at 17. While still a teenager, she had the courage to flee that abuse to protect her young son and get a divorce … in small-town America … during the Great Depression.

I can’t begin to imagine the courage that must have taken.

Meanwhile, my father grew up a few miles away on a rural farm and into another dysfunctional family. In the summer of 1925, my nine-year-old dad was out racing bikes with his little sister. He made it across the train tracks. Arlene didn’t.

She was run over at the ungated crossing and killed — right in front of him. The coroner’s report stated it brusquely: “struck by Nickel Plate Passenger train, neck broken left leg 2 places between knee and ankle.” Dad kept revisiting the site, looking for his sister’s blood on the tracks.

I don’t know how he lived with the guilt. Had I been a girl, I would have shared Arlene’s name.

When he was 17, on a brutally cold day in February of 1934, my dad found his father, of the same name, a long-time drunk, perhaps self-medicating, strung up in the barn, a suicide. Dad picked up a ladder, still sprawled on the floor where his father had kicked it while dying, set it up, climbed it, and cut down the corpse. He immediately quit school and began supporting his mother and her subsequent string of husbands, heavily self-medicating all the while. I don’t know how he lived with the pain.

However.

My parents found Jesus and each other. They met at a square dance. She was 23 and he was 24 when they married. Dad adopted my brother and gave up booze, cold turkey, for good. He worked in a steel mill for three decades, rising from floor sweeper to management until Japanese competition destroyed the company and much of the American steel industry.

In a tough economy, a guy in his 50s without a high school diploma has it especially tough. He became a school janitor for the remainder of his working life. I never heard him complain about it.

Dad’s mother came to live with us after the last of her marriages ended. Grandma’s dementia (we called it “hardening of the arteries”) eventually got so bad that she couldn’t stay with us anymore. She would start fires, leave the gas on, tell crazy stories, and run away from home. She couldn’t remember who she was or find her way back. Mom became a bank teller to pay for her medical care.

The best jobs I had as a teenager were offered to me by people who knew, respected, and loved my parents. I didn’t get those jobs on account of any merit on my part; I got them entirely on the basis of theirs.

Mom and Dad had nearly 60 happy years together, most in the house pictured below, where I grew up, for which they saved and then purchased for $2,700. Cash. It had two bedrooms, one bath, a detached garage, and a granny flat in the back.

I never heard an angry word between my parents (my mom would have used “cross” instead of “angry”). They broke the cycle of abuse.

Mom and Dad waited 16 years for me. By the time I was born, they were 39 and 40, and had pretty much given up hope of having a child together. They had given away my brother’s baby furniture. The history of sadness and abuse was locked away and never mentioned. Had I known their stories then, I hope I would have shown them more grace as a teenager, chafing at the various structures and strictures they built and imposed upon me (and themselves).

Today, I am astonished at their story and grateful beyond explanation for the many blessings I have been given. Once more for emphasis: They broke the cycle of abuse – horrible dysfunction and abuse from which I was largely (and lovingly) shielded.

It seems impossible now but I didn’t know.

I only learned many of the details after Mom and Dad were gone. For all I knew, I grew up in a loving and stable working-class family in heartland America. I was ignorant of what Paul Harvey called, every day on the local radio station (1410 AM), “the rest of the story.” My (now deceased) brother and I became the first members of our extended family to go to college. We got graduate degrees, too. Our lives were (and, in my case, is) full, productive, and happy.

Everything about my parents’ lives and experience screamed that love, family, and children was an absurd, losing proposition. To that point, everything was negative skewness. All the way down.

They took a chance on love anyway, and I’m here because they did. They ended up winning big, as my dad told me early and often. They got enormous positive delta — right-tailed skewness all the way down. They lived what I now like to call a “fat-tailed life.”2

When, why, and how we might take similar risks in life, love, and career is the subject of this edition of TBL and the next. We’ll start with an extended look at why the current culture is far more resistant to such risk-taking than ever before and why we should counter the favored narrative. Part two will seek to address how to do that.

I hope you’ll hunker down with these two (lengthy) missives and let me know what you think. If you are a regular TBL reader, there are themes you will recognize, but I have fleshed things out a lot and expanded the argument.

If you like The Better Letter, please subscribe, share it, and forward it widely. It’s free, there are no ads, and I never sell or give away email addresses.

NOTE: Some email services may truncate TBL. If so, or if you’d prefer, you can read it all here. If it is clipped, you can also click on “View entire message” and you’ll be able to view the entire post in your email app.

Thanks for reading.

Strong-Link Problems

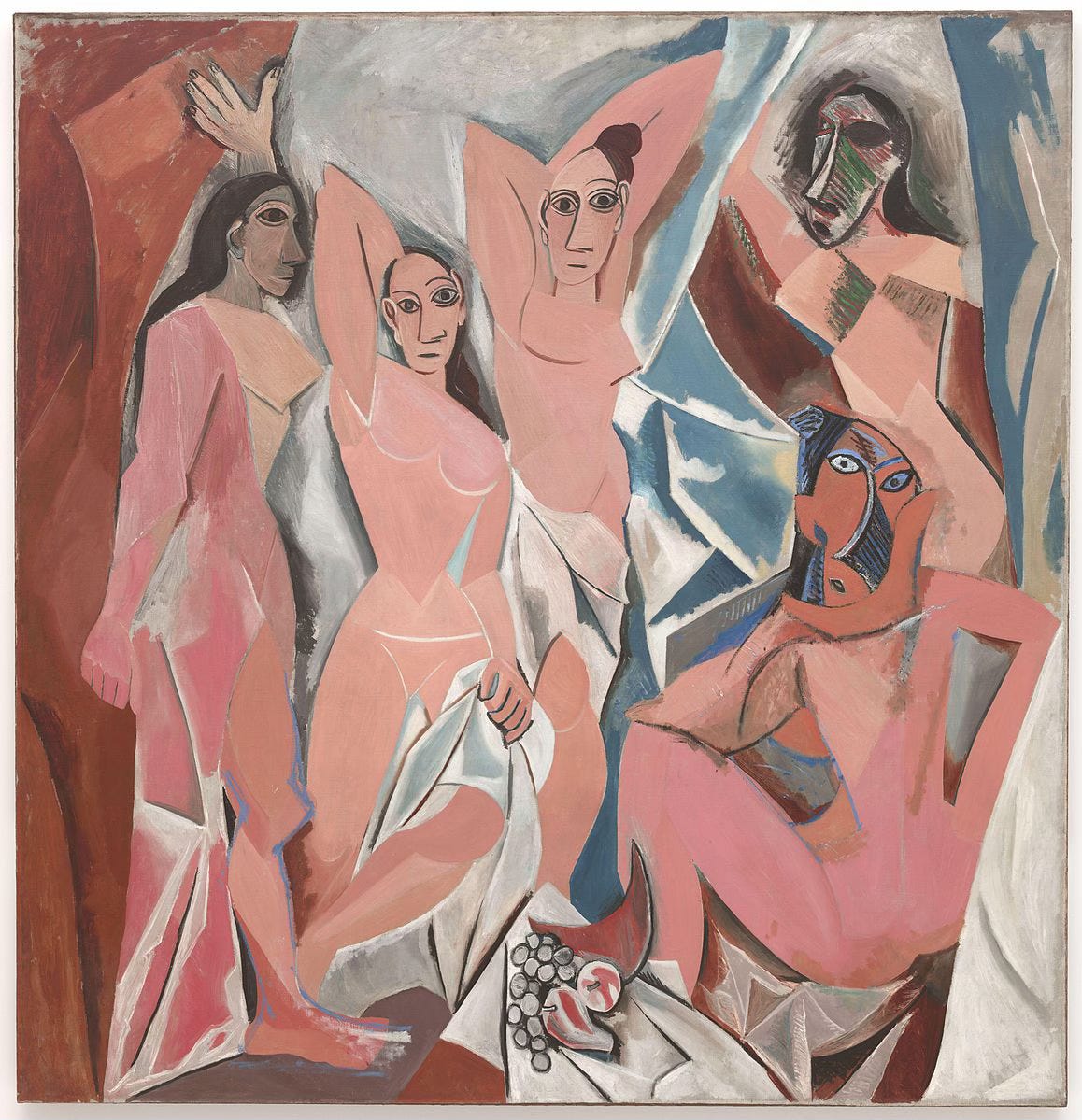

Eighteen years ago last month, Newsweek named a 1907 painting by Pablo Picasso that came to be known as Les Demoiselles d’Avignon the most important painting in the previous 100 years. In 1906, when Picasso began roughing out Les Demoiselles with hundreds of sketches and studies, Monet’s impressionism and Matisse’s brand of fauvism were art’s cutting edge.

Picasso had other ideas.

“Others have seen what is and asked why. I have seen what could be and asked why not,” he said.

Picasso abandoned all then-existing forms, perspectives, and representations of traditional art and idealized beauty with this painting. In much the same way James Joyce’s Ulysses (begun in 1906; serialized 1918-1920; published in 1922) begat modern literature, T.S. Elliot’s The Waste Land (1922) ushered in modern poetry, Schoenberg’s Erwartung (1909) led to modern opera, and Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring (1910) paved the way for modern music, the artistic past was transformed into an artistic future through this painting.

But when the then modestly successful Picasso first showed the piece to a small group of artists, dealers, and friends, he did not get the response he was hoping for. Here’s how Newsweek described it.

“When Matisse saw Picasso’s just-completed, eight-foot-square painting ‘Les Demoiselles d’Avignon’ in the Spaniard’s studio in a ramshackle Paris building nicknamed ‘The Laundry Boat,’ he was shocked at how raw, cacophonic and nasty it looked. Another modernist, André Derain, figured that Picasso had gone so far off the deep end that he’d soon commit suicide. Even Picasso’s loyal patron Gertrude Stein deemed the picture a ‘veritable cataclysm.’ And you know what? It’s still pretty ugly.”

“Pretty ugly” and, simultaneously, “a quantum leap in modern art’s [theretofore] straight-line ‘progress’ from impressionism to pure abstraction.”

Les Demoiselles wasn’t normal art. It wasn’t a linear progression from what had come before. It was wildly different and transformative.

The painting created wide anger and disagreement even amongst Picasso’s closest associates and friends. In one sense, at least, that should not be surprising in that the work was everything that art at the time was not supposed to be (like ugly, disconcerting, and unusual). The painting was not exhibited until 1916 and not widely recognized as a revolutionary achievement until the early 1920s. Still, the work became seminal in the early development of both Cubism and of modern art generally. It is now indisputably a masterpiece.

True creativity is powerful, indeed3 (even if you don’t like it).

No stranger to artistic achievement himself, David Foster Wallace spoke to the process.

“What the really great artists do is they’re entirely themselves. They’re entirely themselves, they’ve got their own vision, they have their own way of fracturing reality, and if it’s authentic and true, you will feel it in your nerve endings.”

Picasso fractured reality, fractured what had come before, and produced something extraordinary.

Science moves similarly (and even more so4), as Thomas Kuhn famously demonstrated, both philosophically and practically,5 with his seminal work, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. He provided both the conceptual framework for scientific advancement via paradigm shifts over against the prevailing paradigm of incremental advance as well as what became a ready example of one.6

In other words, Kuhn singlehandedly altered the way we think about humankind’s most organized and effective attempts to understand the natural world. Ultimately, Kuhn (like all great scientists) refused to take “Yes!” for an answer.

Before Kuhn, science was seen as the addition of incremental new truths built onto the backs of old truths, the increasing approximation of theories to reality and, in the odd case, the correction of past errors. Thus, traditional science saw what amounted to a long and linear march towards “truth,” or at least towards an increasingly greater understanding of the world. This sort of advance is not wildly different from what came before; it is intentionally derivative. And it generally works. Many (most?) things do not work out as planned. So it makes sense to proceed in small reversible steps that encourage learning, adaptation, and revision.

Where the then-standard account sees slow, steady, cumulative progress, Kuhn saw inconsistencies and discontinuities — a set of alternating “normal” and “revolutionary” phases in which fields of study are plunged into periods of turmoil, uncertainty, and angst before a new paradigm emerges. Truly, per Kuhn (paraphrasing Max Planck and well supported by the evidence), science advances one funeral at a time.7

As philosopher Ian Hacking described it in his preface to the 50th anniversary edition of Structure: “Normal science does not aim at novelty but at clearing up the status quo. It tends to discover what it expects to discover.” It is less about answers, especially revolutionary answers, than it is about uncertainty reduction. In Kuhn’s words, it’s “puzzle solving.” You find the formula and then you just repeat it (in a way, that’s the whole story of private equity).

Scientists, no less than the rest of us, see disconfirming evidence and ask if it must be true. For confirming evidence, the only question is whether it can be true. Our belief systems give us the ongoing sense that we have the correct view of the basic structure of reality.8 Accordingly, novelty — true innovation — comes from the revolutionaries.

Revolutionary scientists don’t stand on the shoulders of giants so much as stomp them to death before burying their remains.

Some of science’s best ideas started out as absurdities, dismissed with a laugh and a condescending wave. Historical revolutionary examples include the Copernican revolution, the Big Bang, Darwinism, Mendel’s genetics, quantum mechanics, Roentgen’s accidental discovery of X-rays, germ theory (including the horrible story of Ignaz Semmelweis), and plate tectonics.

Similar examples include the movement in economics from seeing humanity as utterly rational beings maximizing their marginal utility to seeing them as fully human persons capable of great accomplishment, utter evil, immense stupidity (see the previous edition of TBL), and everything in between. Joseph Schumpter’s “creative destruction” provides another example. Clayton Christensen’s disruptive innovation in business provides yet another.

Also: Picasso, Joyce, Elliot, Schoenberg, Stravinsky and more. Bill James and Caitlin Clark, too.

Nature also seems to work that way. For example, literally and figuratively, the distinction is illustrated by contrasting punctuated equilibrium (“evolution by jerks”) with phyletic gradualism (“evolution by creeps”).

The inverse also illustrates the point. If you ask reasonable people if they think there are major ideas widely accepted by the culture at large that will be shown to be false in the future, they may hesitate for a bit, but they will eventually concede: “Of course. It has happened to every generation since the dawn of human history.” Yet offer those same people a laundry list of contemporary ideas that might fit that description, and they’ll be tempted to reject them all.9 It is impossible to examine questions we don’t ask.

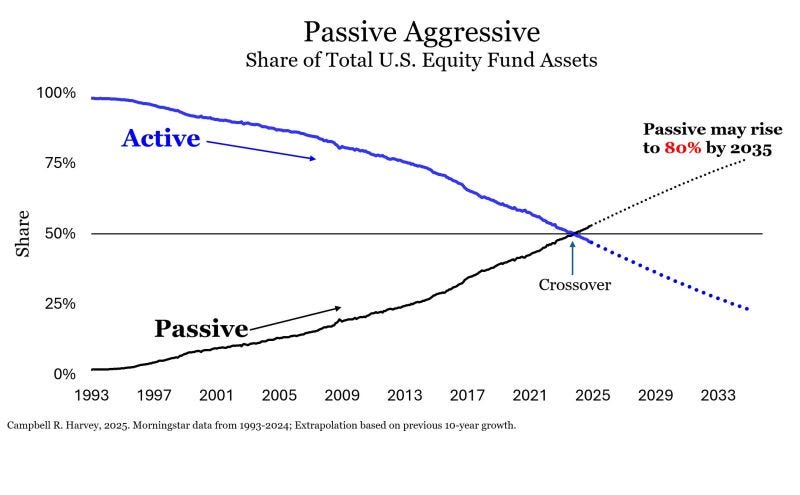

In my day job, the biggest paradigm shift of my lifetime, by far, has been the move from active to passive investing.

Just over 54 years ago, on July 1, 1971, John McQuown and his team of academics created the first-ever index fund. Such passive investing tracks the performance of an underlying index of securities, like the S&P 500. It employs broad diversification without stock picking, active trading, or high fees.

The prophets of indexing, such as John Bogle, founder of Vanguard, ignored investment marketing materials and focused on actual fund performance instead. They found that, despite some short-term (and widely broadcast) successes, almost nobody was achieving better than market performance over the longer-term. They decided that rather than trying to beat the market, they would join it, instead.

Indexing was instantly derided by competitors as being “un-American.” Such complaints continue apace.10 Fidelity Chairman Edward Johnson spoke for most of the investment world when he said he couldn’t “believe that the great mass of investors are going to be satisfied with receiving just average returns.”

Mr. Johnson was dead wrong. And stuck in an old paradigm of the past.

Some $16 trillion is now invested in index funds. More money is invested in passive vehicles than in active funds overall. It isn’t hard to figure out why. Through year-end 2024, nearly 95 percent (94.11 percent, to be exact) of active funds underperformed their appropriate passive benchmarks over the previous 20 years, the longest period for which data is available. And, because of survivorship bias and style drift, that figure significantly understates the extent of passive outperformance.11 Moreover, there is no way to ascertain which active funds will outperform ahead of time.

Activists claim there is some investment secret sauce (or sauces) that allows them to beat the market. There may be.12 However, proponents of passive investment made a simple, scientific demand of the activists: “Show me.” For more than half a century, the activists have failed to do so (again, through year-end 2024, nearly 95 percent of active funds underperformed their appropriate passive benchmarks over the previous 20 years, the longest period for which data is available; or, if you’d prefer, recall Warren Buffett’s famous bet).

On the other hand, as my friend Morgan Housel said, “‘Excellent for a few years’ is not nearly as powerful as ‘pretty good for a long time.’ And few things can beat ‘average for a very long time.’ Average returns for an above-average period of time lead to extreme returns.” Accordingly, the great investment debate of my lifetime has been decided. Passive investing has won. In a runaway.

Shift happens.

Intentionally Derivative

When I was a kid, my hometown had an egg hunt on the Saturday before Easter. Hundreds of multi-colored plastic eggs were hidden throughout the high school football stadium. When discovered, each could be turned in for a candy bar except for one golden plastic egg, which could be redeemed for a chocolate Easter bunny. No doubt hollow. The rules prohibited holding on to an egg while searching for the grand prize. I was a rule follower who was determined to “go for the gold.” When I didn’t succeed, I was left candy-less.

I should have “indexed” and taken the average return.

Assume there were 500 eggs that offered candy bars with a given value (x) and the golden egg was (generously) worth 10(x). That means the expected value of the pool of eggs was 1.02(x) per egg. Had I “settled” for an ordinary egg — I passed up dozens — I would have gotten nearly all the value I could have expected: 1(x) out of 1.02(x). Instead, I got no candy at all.

In this instance, the right choice reflects an “index mindset,” in John Luttig’s evocative phrase, referencing index investing. Very broadly speaking, it favors average results over extreme ones, machines over men, a bird-in-hand over two in the bush, relative over particular truth, function over form, popularity over reality, quantity over quality, liquidity over friction,13 credentials over knowledge, mandate over merit, efficiency over exploration, passivity over action, predictability over tails, determinism over freedom of choice, mistake avoidance over insight, evolution over revolution, adaptation over reformation, safety over risk, diversification over concentration, preservation over creation, velocity over due diligence, optionality over commitment, the general over the specific, growth over profit, bureaucrats over entrepreneurs, and normal over revolutionary.

The index mindset is about risk mitigation rather than ambition. It is about management and administration rather than opportunity. It is about regulation rather than innovation. It is about the efficient frontier rather than the bleeding edge. It is about scale and cost efficiency rather than uniqueness and quality. It is about extraction rather than creation. It is about playing the probabilities rather than changing the game.

None of us wants to end up on the wrong side of maybe (or, as math geeks would have it, the wrong side of variance).

The index mindset makes your business more efficient. It allows you make more widgets faster and cheaper. It allows you to optimize your process. It says nothing about coming up with the original widget. It extracts every ounce of value out of existing structures rather than creating something new.

The index mindset is the wide and smooth road rather than the untraveled one. It allows you to appear good without truly having the goods.

The index mindset doesn’t go for the gold, doesn’t dare to dream, doesn’t run for president, doesn’t take leaps of faith, doesn’t take the last shot, doesn’t go out on its own, doesn’t create the next big thing, doesn’t go all-in, doesn’t storm the beachhead, and doesn’t demand (or expect) true love.

The index mindset is all evolution and incrementalism but no revolution.

Since it’s popularization by Moneyball, both the book by Michael Lewis and the movie, the index mindset has spread throughout culture like a virus (for good and for ill — more on the ill later).

The index mindset figures out what’s really happening, instead of what is assumed to be happening, and seeks to exploit that knowledge and then optimize it.

The results have been astonishing. The change has been extraordinary.

It didn’t happen immediately, but as with investment indexing and moneyball (the process, not just the book or film), the index mindset has carried the day in today’s culture. Statistical understanding, risk avoidance, and optionality now generally dominate our current thinking.

In philosophy, we’ve seen a shift from a capital-T Truth to a multitude of small-t truths — “your truth” and “my truth” — within a moral relativism. In physics, we’ve seen a shift from a certain Newtonian physics to probabilistic quantum mechanics.

In politics, globalism replaced nationalism after World War II. Fewer and fewer of us accept the idea of American exceptionalism anymore.

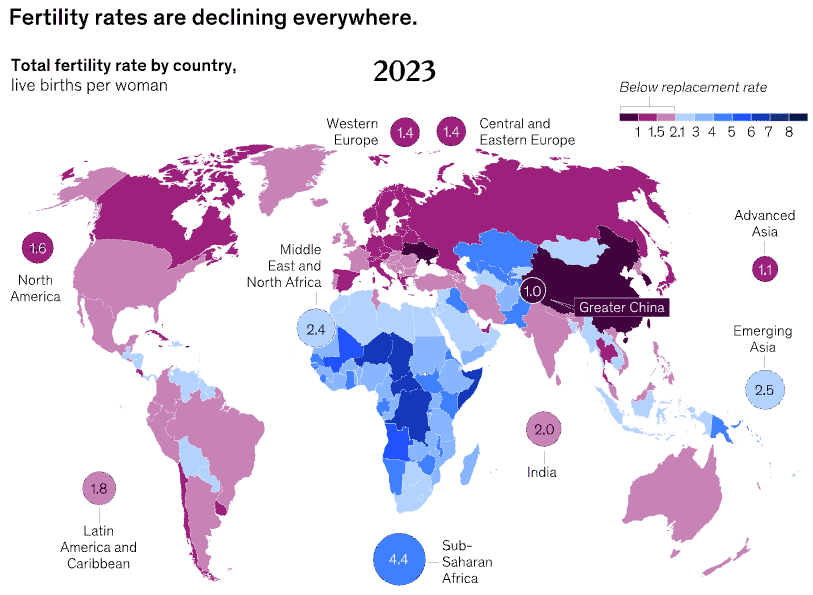

We index our love lives by diversifying relationship capital across apps and platforms and fail to commit to marriage and family. Just a few decades ago, marriage was the rule and marriage at a young age was common, with partners committed until death parted them. Not anymore. Today, marriage comes six years later and schooling lasts five years longer. Divorce is routine. And, today, with birthrates below replacement levels in the U.S. and worldwide, children are more a burden to be avoided than a blessing to be nurtured.

Similarly, one great friend trumps 100 acquaintances.

As a kid in the 1960s, I roamed all over creation, all day (in the summer, at least). I rode my bicycle freely, played baseball across town, and explored the woods “down at the creek” (pronounced “crick”), all without informing my parents of my whereabouts. The protagonists in Beverly Cleary’s children’s books did, too. How I spent my time in the summer was mostly up to me. My parents rarely knew (exactly) where I was.

That’s no longer the way things are done.

As NPR reported about the Thomas family in the north of England, in 2007, the great-grandfather of the clan, age eight, could walk six miles alone to go fishing. But each successive generation had less freedom until the youngest Thomas, at age eight, didn’t leave his yard. If there is an eight-year-old Thomas today, I bet he doesn’t go outside unsupervised at all. Even though crime rates are much lower today, parents are much more fearful and much more restrictive.

One major study found that 34 percent of children do not play outdoors at all on school days. Even on the weekends, 20 percent stays inside. Their lives are fully programmed, supervised, controlled, refereed, and micromanaged.

Meanwhile, parents of “free range” kids risk arrest for letting them walk home from school alone. Young people have followed their parents’ lead, taking fewer risks than any generation in history: They aren’t moving out, aren’t having sex, aren’t drinking, aren’t driving, and aren’t even riding bikes. Kids want to play outside, but risk-averse parents won’t let them unless they are supervised, so they’re stuck inside scrolling on their phones.

It’s the index mindset.

Artists should be well positioned to reject the index mindset both in the sense that they generally think we can recognize good over bad, great over good, and that Truth and “true love” are worth seeking and even dying for. Yet art is an indexed endeavor, too. We are oh-so-eager to proclaim that those who don’t learn from the past are doomed to repeat it — right before buying and watching a movie with a numeral in the title. For the seventh time.

Seventy percent of the popular music in the American market is old music.14 Summer concert tours are dominated by “classic rock” performers and other senior citizens. Studios are rehashing stories continuously — Harry Potter is getting a reboot, Tom Cruise just did the eighth installment of the Mission Impossible series nearly 30 years after the first one (which itself was a reboot of a of a TV series three decades before that), and nine out of ten of the highest grossing movies in 2024 were sequels. The one exception, Wicked, was an adaptation of a 22-year-old Broadway musical that was an adaptation of a 30-year-old novel that was a prequel of a 86-year-old movie that was, itself, an adaptation of a 125-year-old novel, The Wizard of Oz.15

Oh, and robots are now “creating” statues. Whole buildings are next. Even AI “art” is getting better.

College and career choices (like sports) have become indexed and hedged. Applicants (and their parents) spend enormous amounts of money trying to moneyball the system. SAT test prep, anyone?

The same impulses that drive us to safety also cause us to settle.

Algorithms control our social media feeds, the advertising we see, the entertainment (“content”) put in front of us, and how American business interacts with consumers.16 The more our decisions are algorithmically derived, the more humanity will be required to stand out. The more we are algorithmically poisoned, the more humanity will be needed to sort things out. The index mindset is comfortable — avoiding decisions requires the least amount of effort. But if you index across every domain, you lose any differentiating features, becoming little more than an average of everyone else. Usually less.

It’s all intentionally derivative.

Artificial Intelligence will increasingly accelerate this trend. If you can’t write it, you don’t understand it, but many let AI do their writing for them. “Slop” and “brain rot” are ubiquitous. And, it should be noted, monocultures are fragile and prone to collapse because of common weaknesses. We now have a “quantified self,” which has given rise to products like Fitbit, Strava, and Apple Watch, and the stated goal for many of “transhumanism.” Perhaps our greatest existential question going forward will be whether we will live as men (and women) or machines.17

The crisis of our time is the radical reduction of humanity to a flow of information. Indeed, some tech pioneers aspire to “eternal life” achieved by uploading our minds to a digital cloud. The logical extension of the index mindset would throw off the messiness of human relationships to fall in “love” with a bots instead (is it any wonder Americans are lonelier than ever?).18 However, humanity and rationality are not identical; humanity cannot be reduced to ones and zeroes.

Because it emerges in liquid markets and often works, and because technology supercharges liquidity generally, the index mindset won’t be going away. Such ever-increasing liquidity is an enemy of community. The question is if or when you should follow the trend and participate.

As Charley Ellis first noted, investing (like financial planning generally) is a “loser’s game” much of the time, with outcomes dominated by luck rather than skill and high transaction costs. Charley used tennis to illustrate the point. For most of us, most of the time, tennis is a loser’s game. We don’t possess the skills to play well consistently. Trying harder to make great shots only makes matters worse. Most of us are better off simply trying to keep the ball in play. It’s better to try to outlast rather than outclass an opponent. If we keep the ball in play we give the opponent the opportunity to make errors. That’s a loser’s game. The results are dominated by what the loser does.

On the other hand, professional tennis is a winner’s game, with outcomes based predominately upon the winner’s better shots. Watch amateurs play and you will see most points lost (rather than won) due to unforced errors. However, at the professional level, only about one-third of points are decided that way. In other words, if I avoid mistakes I will win a lot of matches at my local park. But you won’t win Wimbledon that way.

Loser’s game techniques, powered primarily by risk aversion, incubated the index mindset. These center on being data-driven, low cost, probability fueled, diversified, and process-focused to eliminate errors and retain optionality. It’s “moneyball,” literally and figuratively, for baseball and beyond: Don’t Make Outs.19

These loser’s game techniques work really well during normal periods, for science and everything else. The index mindset is made for normal periods. AI, being intentionally derivative, works exceedingly well for normal things in normal periods. Derivative sameness has never been cheaper or more accessible. It’s everywhere.

Most “loser’s game” situations are best thought of as “weak-link” problems.20 A weak-link problem is one for which the best response is to improve the weak-links. They are problems where overall quality depends on how good the worst stuff is. You fix weak-link problems by making the weakest links stronger, or by eliminating them entirely. Technology, the internet, and AI have made business, like investing, increasingly a weak-link problem. Faster. Cheaper. Optimize.

As the recent pandemic showed conclusively, supply chains are a weak-link problem. If one link in the chain fails, the chain breaks. Safety is primarily a weak-link problem. Making the safest car a little safer is good, but getting the Ford Pinto off the road was a game-changer. The space shuttle Challenger crashed because of the failure of a single rubber O-ring gasket that cost pennies. Nuclear weapons proliferation is a weak-link problem. Nuclear weapons can always be handled more responsibly, but the outlier rogue nations are the true threat.

It’s easy to find people whose answer to everything is to moneyball it. But not every problem is a weak-link problem.

Meaning is Expensive

For most of human history, life was cruel, brutish, and short (echoing Thomas Hobbes21). Our big goal was to avoid dying: how to eat and avoid being eaten. Any concept of agency in the modern sense was preposterous. Few escaped their (often dreadful) circumstances. Boys mostly did what their fathers did or, before that, their tribes did. Girls had dimmer hopes than that.

Using the tools at their disposal, literal and figurative, found and forged, humans fought to stay alive. The earliest mental tools were instruments as blunt as their physical tools: sensory perception, gestures, mimicry, intuition, language, trial and error, rudimentary arithmetic (often little more than counting), and stories. They aren’t necessarily accurate, but they are instinctive, intuitive, memorable, and powerful.22

These primal tools worked well enough in the ancient world. Over time, practices and customs developed, many of which were surprisingly effective. But they work less well in the modern world.

Math works better than intuition because the universe has symmetry and patterns which allow us to explore, describe, understand, and exploit it. As Galileo said, “mathematics is the language with which God has written the universe.” Science works because we are inherently biased and error-prone. In essence, the scientific method is the systematic limitation and reduction of human error.

As life became more complex, humans developed more complex, systematic, and probabilistic mental tools to help themselves stay alive and, eventually, to enhance their lives: careful definitions, analysis, quantification, more sophisticated maths, increasing precision, systemization, optimization, and the scientific method. Thus, the index mindset.

These different sets of tools reflect crucial differences in how people today live in and understand the world. Our primal tools are narrative and qualitative. Our newer tools are more abstract, logical, and quantitative. They are (imperfectly) reflected in how we think of “heart” and “head,” sacred and secular, art and science, men and machines.

Our newer tools are so effective our older tools are often denigrated or ignored.

These distinctions aren’t new, for course. They can be seen in Alasdair MacIntyre’s critique of modernity, for example, the left brain/right brain distinction at the heart of Iain McGilchrist’s brilliant The Master and His Emissary, Daniel Kahneman’s metaphor of the brain’s “System 1” and “System 2,” Jonathan Haidt’s parable of the elephant and the rider, Isaiah Berlin’s foxes and hedgehogs, and in other places throughout relatively recent history.

They all recognize, at least implicitly and practically, that not every problem is a weak-link problem. Now that we have largely solved day-to-day survival (in most of the world, at least), meaning and mattering are life’s great quests. Not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted. “Precision often destroys the dream,” as Gauguin would have it. Indexing is simple and cheap. Meaning is expensive.

Meaning and mattering are strong-link problems. Intelligence works for an orderly world, for weak-link problems. Only wisdom works for a chaotic world, for strong-link problems.

AI surely has the potential to disrupt and reorder economic, cultural, and political life. Yet, it is still (and merely) a brute force solver of puzzles through observation, analysis, calculation, recalculation, modification, adaptation, repetition, trial, and error. Strong-link problems require something more like alchemy,23 but an alchemy that works.

The index mindset offers index returns. A fat-tailed life (full of right-tailed skewness) — one that is meaningful and that matters — is for those people for whom and those times for which “fine” isn’t sufficiently aspirational.

The novelist, Walker Percy, argued that moderns tend to love catastrophes (secretly) because it makes a person feel alive. For modern men and women, death comes less from danger as commonly conceived but from a lack of meaning or purpose. The sense that, all of a sudden, everything is falling apart, can jolt us out of that kind of torpor. The protagonist, Will Barrett, in Percy’s novel, The Last Gentleman, reflects on how happy his father was when he remembered Pearl Harbor. It was not that his father loved violence and death. But when he thought about Pearl Harbor, he had a purpose in life. “War is better than Monday morning,” Will concludes.

The fat-tailed life is also (and only) for those willing to pay the price of different. For most people and companies, in most situations, it’s easier to copy what seems to be working with as little effort and adjustment as possible. They aren’t willing to risk being different and wrong. Being the same and wrong is no big deal. It’s often well regarded and profitable. Slop sells.

Being different and wrong is career and business suicide. But being extraordinarily different and right, especially where it’s non-quantifiable, is where today’s great opportunities lie.

The index mindset seeks a regulated, carefully engineered world with adaptation and adjustment. A fat-tailed world is one of constant creation, discovery, dynamism, disruption, and difference. Nobody will ever get to Mars by climbing successively taller mountains.

The problems that need solving to get a fat-tailed life are overwhelmingly strong-link problems. And once I started seeing them, I couldn’t stop.

Societally, we tend to treat the education of children as exclusively a weak-link problem, focusing immense amounts of attention on the students who have the most difficulty. We assume the highest achieving students will be “fine.” That’s okay as far as it goes but it’s no way to foster the extraordinary. Nobody won a Nobel Prize for “fine” work.

Beauty and the arts are strong-link problems. Milli Vanilli, Thomas Kincaid, and Danielle Steele are bad but irrelevant. Seek out the extraordinary.

The NFL Draft is overwhelmingly a weak-link problem. Avoiding errors matters demonstrably more than making shrewd choices. However, getting the right quarterback is a strong-link problem. And in the salary cap era, the most important element of championship teams is having a top-tier QB.

Routine medicine is a weak-link problem. Avoid the bad doctors and you’ll be fine. Any reasonably competent doctor can set a broken leg or prescribe an antibiotic. Cutting-edge medicine is different. It’s a strong-link problem because only the best will do. If you have a esoteric, difficult-to-diagnose condition, you want to see the best doctor, not merely a competent one.

Scientific progress has slowed, thanks to our treating it as a weak-link problem. We fund more research than ever and get way less bang for our buck. We spend 15,000 years of collective effort every year on a peer review system that doesn’t do the job. Fraud, aided by “research paper mills,” has become a full-blown industry. Fraudsters can publish dozens of papers before they get caught, if they get caught at all. Reviewers are less likely to green-light papers and grants if they’re novel, risky, or interdisciplinary. The U.S. government spends ~10x more on science today than it did in 1956, adjusted for inflation. We’ve got loads more scientists, and they publish way more papers. And yet science is less disruptive than ever, scientific productivity has been falling for decades, and scientists rate the discoveries of decades ago as worthier than the discoveries of today.

That’s the index mindset at work. It’s intentionally derivative. We need the extraordinary, instead.

The scientific establishment treats science as a weak-link problem, focusing on credentials, catching quacks and fakes, promoting incremental advance, and crushing dissent. And normal science is a weak-link problem. However, extraordinary, cutting edge, world-changing science is a strong-link problem. So is venture capital. All that matters is how good the best stuff is and how big a difference it makes.

What and who you surrender your life to are strong-link problems. Moral urgency is a strong-link problem. Evil is a strong-link problem. The index mindset is impotent against evil because good and evil are utterly different things, not merely incrementally different on a sliding scale.

Our world desperately needs to seek out and properly attack our strong-link problems, of which there are plenty.

The Big Finish

The richest people in the world are overwhelmingly founders of businesses. The most famous people in the world are athletes, artists, and political leaders. Disproportionately, the happiest people in the world are married with children. What binds these people together is a willingness to buck the odds and “go for it” in their personal or professional lives. Each of these traits demand a “risk-on” approach to life. Greatness doesn’t come by committee.

C.S. Lewis got it right.

“There is no safe investment. To love at all is to be vulnerable. Love anything, and your heart will certainly be wrung and possibly be broken. If you want to make sure of keeping it intact, you must give your heart to no one, not even to an animal. Wrap it carefully round with hobbies and little luxuries; avoid all entanglements; lock it up safe in the casket or coffin of your selfishness. But in that casket — safe, dark, motionless, airless — it will change. It will not be broken; it will become unbreakable, impenetrable, irredeemable. The alternative to tragedy, or at least to the risk of tragedy, is damnation. The only place outside Heaven where you can be perfectly safe from all the dangers and perturbations of love is Hell.”

So did Jeff Bezos.

“Outsized returns often come from betting against conventional wisdom, and conventional wisdom is usually right. Given a 10 percent chance of a 100 times payoff, you should take that bet every time. But you're still going to be wrong nine times out of ten … We all know that if you swing for the fences, you're going to strike out a lot, but you're also going to hit some home runs. The difference between baseball and business, however, is that baseball has a truncated outcome distribution. When you swing, no matter how well you connect with the ball, the most runs you can get is four. In business, every once in a while, when you step up to the plate, you can score 1,000 runs. This long-tailed distribution of returns is why it's important to be bold. Big winners pay for so many experiments.”

Cormac McCarthy, too: “You would give up your dreams in order to escape your nightmares and I would not. I think it’s a bad bargain.”

“Courage looks like stupidity to an audience of maximizers,” as Kris Abdelmessih says. But we should strive for courage, boldness, and love anyway. Despite the odds.

The Big But

To this point, the argument is powerful, but limited. There’s a big “but.” All we have so far is a fleshed-out commencement speech.

Follow your dreams. Be bold. Take chances.

The next TBL will look at when and how to do that. It’s a strong-link problem.

Totally Worth It

I appeared on Matt Zeigler’s “Just Press Record” recently and had what I think is an excellent conversation about sports and shared experiences. I was working on this TBL when we recorded it and talked about it briefly at the end.

Sixty years ago last week, Bob Dylan recorded one of the great songs of all-time, “Like a Rolling Stone,” which reached #2 on the Billboard charts and has only grown more iconic in the decades since. As Columbia Records’ Shaun Considine later recounted to The New York Times, Dylan’s song was almost not released as a single. Record executives wanted to cut the six-minute song in half, but Dylan refused. It was only after Considine shared the song with two influential New York radio tastemakers — who, upon listening to it, swiftly called up Columbia Records — that the record label agreed to release the song as a single. It hit the airwaves almost a month after recording and received a “mixed” reaction at the Newport Folk Festival five days after that.

Feel free to contact me via rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or on Twitter (@rpseawright) and let me know what you like, what you don’t like, what you’d like to see changed, and what you’d add. Praise, condemnation, and feedback are always welcome.

Of course, the easiest way to share TBL is simply to forward it to a few dozen of your closest friends.

Still Life, by Louise Penny, is the first book in her series featuring Quebecois detective Armand Gamache. Unlike the stereotypical fictional sleuth, Gamache is not broken, haunted, or deeply flawed, but a genuinely decent sort who seeks out opportunities to help others. Tellingly, he suggests to a new and struggling trainee on his team that four sentences can point toward wisdom: “I’m sorry. I don’t know. I need help. I was wrong.”

You may hit some paywalls below; some can be overcome here.

This is the best thing I’ve read recently. The loveliest. The sweetest. The most amazing. The most important. The most harrowing. The most absurd. The best thread. Great coaching. After five MLB games, an all-star. Well done, Coach Prime. Puzzling. Who really invented basketball? Buc-ee’s. Good Vibrations.

Please send me your nominations for this space to rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or via Twitter (@rpseawright).

Saoirse Ronan stars in a video marking the fiftieth anniversary of “Psycho Killer” from Talking Heads. Lots of quickly intercut scenes show her incessantly repetitive 9-5 life. Her behavior becomes more and more erratic, but nobody in her life seems to notice.

Bob Dylan: “Sam Cooke said this when told he had a beautiful voice: He said, ‘Well that’s very kind of you, but voices ought not to be measured by how pretty they are. Instead, they matter only if they convince you that they are telling the truth.’” Nobody thinks Bob has a beautiful voice, but a truth-teller he was and is.

Benediction

On November 20, 1983, along with more than 100 million other Americans, I tuned in to ABC’s television movie, The Day After. It boasted a big-time cast and postulated a full-scale nuclear confrontation between NATO and the Warsaw Pact nations. It was a kind of God’s Not Dead for the no-nukes crowd, and equally heavy-handed. When the film ended — sadly and bleakly — I was astonished to hear the 1787 hymn, How Firm a Foundation, adapted for Virgil Thomson’s Symphony on a Hymn Tune, play over the devastation and the credits. The irony wasn’t lost on me. This week’s benediction is a much newer, bluegrass version of that old hymn from Chelsea Moon with the Franz Brothers.

“The soul that on Jesus hath leaned for repose | I will not, I will not desert to his foes | That soul, though all hell should endeavor to shake | I’ll never, no, never, no, never forsake!”

We live on “a hurtling planet,” the poet Rod Jellema informed us, “swung from a thread of light and saved by nothing but grace.” To those of us prone to wander, to those who are broken, to those who flee and fight in fear – which is every last lost one of us – there is a faith that offers hope and love. May we offer grace first and live the Truth before speaking it. And may grace have the last word, too. Now and forever. Amen.

As always, thanks for reading.

Issue 190 (July 20, 2025)

I’ve told this story before, in a different context.

It’s human nature, the chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, Jerome Powell, said on January 29, to assume that risk outcomes are normally distributed around the mean. But in the economy, and elsewhere, “it’s not a normal distribution. The tails are very fat, meaning things can happen way out of your expectations. It’s never not that way.”

Scientists at the University of Amsterdam studied brain scans of people looking at paintings. In every instance, original paintings had the most powerful response; reproductions just don’t elicit the same intensity of feeling.

As Kuhn noted: “Picasso’s success has not relegated Rembrandt’s paintings to the storage vaults of art museums.”

The first review of Structure published by Scientific American didn’t see much of interest. The last sentence reads: “It is much ado about very little.” The book sold only 919 copies the first year. Today, on the other hand, it is one of the most cited academic books of all-time. Smallpox provides another example. It is the only human disease that has ever been eradicated. It used to kill an estimated 5 million people every year. Today, nobody dies from it. That’s mostly because of the smallpox vaccine developed by Edward Jenner. However, Philosophical Transactions, one of the more prestigious scientific outlets of its day, rejected Jenner’s paper describing his test results. Similarly, only 75 people bought Bill James’ first Baseball Abstract. Today, analytics drive Major League Baseball. That’s how paradigm shifts work. Because they are so different, or controversial, they don’t catch-on right away.

Karl Popper argued that science advances due to the logical application of the scientific method and positive advancement. His philosophy of “logical positivism” gained much traffic in the scientific fields people started paying more attention to what actually happened instead of what they hoped had happened. Issac Newton was an alchemist who believed in magic and Darwin was heavily influenced by the work of economist Thomas Malthus (whose theories of economic growth were completely wrong). Science is hardly linear, even discounting paradigm shifts.

The image of a butterfly’s wings causing a hurricane thousands of miles away is a potent metaphor for chaos theory. Scientists have now identified what must be the first butterfly that benefits from hurricanes devastating their environment. A 36-year dataset confirmed that the Schaus’ swallowtail butterfly, which lives on the island of Elliott Key, Florida, and is seriously endangered, does remarkably well after storms ravage its habitat. Their population hit an all-time low of 56 in 2007 but, as of 2021, there were about 4,400 of them. This population gain spiked shortly after 1992, 2005, and 2017, which is when Hurricanes Andrew, Wilma, and Irma battered the region. Scientists attribute the phenomenon to gaps in the tree canopy that let light hit the forest floor and allow understory plants to bloom, feeding the caterpillars and butterflies. The death of a great scientist can clear the field for the sprouting of new scientists and new ideas.

We don’t self-evaluate very well. Sherlock Holmes remains perhaps the world’s most vibrant literary creation, still the protagonist in new stories, books, movies, and television, decades after his creation. Yet, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle considered his Sherlock stories “a lower stratum of literary achievement” and thought his novels were far better. But few can name any. He also professed a rigid empiricism … and believed in fairies.

It’s the “end of history illusion.”

Because almost nobody outperforms an appropriate benchmark, it’s easy to miss the sorts of returns that would be possible if anybody were truly good at picking stocks. In 2024, the S&P 500 did great (+25.02 percent, including dividends), but Palantir Technologies did a lot better, returning 340 percent. Had you rotated into the best S&P 500 stock each month in 2024 – SMCI in January (+89 percent); SMCI again in February (+60 percent); VST in March (+28 percent); and so on through AVGO in December (+43 percent) – your portfolio value would have grown roughly +7,073 percent for the year. Had you rotated into the best S&P stock each week, your portfolio would have returned over 10,000 percent. Had you owned just the best performing S&P 500 stock each day (Moderna on January 2, +12.6 percent; Southwest Airlines on January 5 +4.7 percent…), your return for the year would have been astronomical; your portfolio value would have grown to more than the current value of the whole market.

Indeed, as one long-term study found, before fees and costs, active managers (on average and in the aggregate) outperform by 5 basis points. After coast and fees, not so much.

“The hard makes it great.”

Popular songs stay popular about twice as long, too. In 1960, the average song in the Hot 100 stayed on the chart for 6 weeks, the average song that made the top 40 stayed there for 8 weeks, and the average song to make the top 10 stayed there for 9 weeks. In 2025, the average song has stayed in the Hot 100 for 9 weeks, the top 40 for 15 weeks, and the top 10 for 18 weeks.

The Rolling Stones’ 2024 “Hackney Diamonds” tour was sponsored by AARP, which offered its members early access to tickets, photo opportunities, and interactive experiences.

The algorithm, which doesn’t care about truth, coherence, or consequences, is designed for engagement. Because it is so effective and efficient at it, much of our lives are now dominated by it. Accordingly, we now have an extraction economy (Kyla Scanlon’s telling phrase), where things are created solely for consumption rather than purpose and where “content” is king. To the ongoing debate over whether truth is discovered or revealed, today’s digitally-dominated world adds a third possibility: truth is performed.

As Wendell Berry wrote: “It is easy for me to imagine that the next great division of the world will be between people who wish to live as creatures and people who wish to live as machines.” According to the most expansive vision of AI “progress,” we will move from dependence to obsolescence linearly, then exponentially (slowly, then suddenly), before we are eliminated.

We like to think our risks are calculated. But if they are, we’re very bad at math.

The weak-link problem versus strong-link problem formulation comes from The Numbers Game, a terrific book about soccer analytics (soccer is a weak-link problem commonly attacked like a strong-link problem) by Chris Anderson and David Sally.

Leviathan, i. xiii. 9.

Bryan Karetnyk’s Times Literary Supplement review of a new edition of the 1937 Short History of the USSR: “Picture a rather bizarre scene. It is the summer of 1937, and Stalin’s Great Terror is at its zenith. Yet in between signing list after list of names marked for execution, the Father of Nations removes to his dacha at Kuntsevo, west of Moscow, where, undisturbed, he sits down to edit a set of galleys for a new history textbook intended for schoolchildren across the Soviet Union. Under the circumstances, this excursion from mass murder may seem unexpected, extraordinary even. But in a land where power has forever rested on narrative, history has always been a vital instrument of governance and control.”

As the historian of science Lauren Kassell explained: “Alchemy was an arcane art. Its traditions were learned through divine inspiration, instruction by a master under an oath of secrecy, and the study of esoteric texts.” Isaac Newton wrote 650,000 words about alchemy. John Maynard Keynes, who bought many of Newton’s manuscripts, argued that “Newton was not the first of the age of reason. He was the last of the magicians.”

Bob, this is some of the best and most inspiring writing I've read on Substack. Original, thoughtful and wonderful storytelling. Well done!

One of your best Bob! I’m going to read this many times over in the next week.