Always Invert

In honor of the new book by Barry Ritholz.

The indispensable Barry Ritholz has a terrific new book out, How Not to Invest. You should buy and read it. Its focus is on avoiding investment mistakes. In honor of Barry and his book, this TBL will have a look at mistake avoidance from a slightly different perspective.

If you like The Better Letter, please subscribe, share it, and forward it widely.

If you’re new here, check out these TBL “greatest hits” below.

NOTE: Some email services may truncate TBL. If so, or if you’d prefer, you can read it all here. If it is clipped, you can also click on “View entire message” and you’ll be able to view the entire post in your email app.

Thanks for reading.

Always Invert

My aunt and uncle lived their adult lives in Cocoa, Florida, just a stone’s throw from the Kennedy Space Center. My uncle worked as a carpenter for the space program for many years. As a kid, I was visiting on the day an early Gemini mission launched. I watched the countdown to lift-off on television, commentary by Walter Cronkite. When the rocket cleared the tower on screen in black-and-white, I ran out to the front yard and watched it ascend toward space in living color.

By the frigid morning of January 28, 1986, at 11:38 a.m., my late parents had retired and moved next door to my aunt and uncle. Their space flight routine was just like mine had been so many years before, although theirs was now a color television. But as they stood in their front lawn and watched the advent of America’s 25th space shuttle mission, disaster struck 66 seconds into the flight. A few seconds later, the crew and the world realized it.

On the way to space, 73 seconds in, pilot Mike Smith muttered, “Uh oh....” That was the last comment captured by the crew cabin intercom recorder, although the crew likely survived until impact. While traveling almost twice the speed of sound, the Challenger broke apart nine miles up in the sky, the details obscured by billowing vapor.

Fire and smoke engulfed the supersonic shuttle. Crew members struggled to engage their reserve oxygen packs. Pieces of Challenger rained to earth. Two minutes and forty-five seconds after the explosion, the crew chamber crashed into the Atlantic Ocean at over 200 mph, killing all seven people aboard, including the first teacher in space, Christa McAuliffe.

As President Ronald Reagan said that evening, in his address to the nation, quoting the poet, John Gillespie Magee, Jr., “We will never forget them, nor the last time we saw them, this morning, as they prepared for their journey and waved goodbye and ‘slipped the surly bonds of earth’ to ‘touch the face of God.’”

By the next morning, the decision had already been made to appoint an external review commission to investigate what had happened and what had gone wrong. This was a notable departure from the Apollo 1 fire investigation of 1967 (which killed three astronauts on the ground during training). That earlier investigation was controlled by NASA, providing insulation from political or organizational criticism. On February 3, President Reagan announced that a 13-member commission chaired by former Secretary of State William P. Rogers would lead the investigation and recommend corrective action. Rogers felt pressure to find the technical cause of the accident, to fix it, and to absolve NASA of any responsibility quickly, so that the space program could get back up to speed, and return to business as usual.

That didn’t happen.

The commission found that the disaster was caused by a failure of an O-ring, a circular gasket that sealed the right rocket booster, causing pressurized hot gases and eventually flame to “blow-by” the O-ring and contact the adjacent external tank, causing structural failure. This failure was attributed to a design flaw, as its performance could be compromised by factors including low temperatures on the day of launch.

More broadly, the Commission concluded that it was “an accident rooted in history” because, as early as 1977, NASA managers had not only known about the O-ring’s flaws, but that its flaws held the potential for “a catastrophe of the highest order.” Indeed, an engineer involved in the manufacture of the O-rings predicted as much six months before launch (and ended up being exiled by the company for his trouble). Moreover, on the night before the flight, engineers from Morton Thiokol (manufacturer of the solid fuel boosters) stated their concerns about the O-rings and urged a delay, but these concerns were deemed excessive by NASA management eager for launch.

Commission member and Nobel laureate Richard Feynman – the “smartest man in the world” – carefully distanced himself from the official investigation, choosing instead personally to interview as many engineers involved in the project as he could, away from bureaucrats and other officials. Feynman is a problematic hero, to be sure, but in this instance still a hero.

Commission member Sally Ride, the first female U.S. astronaut, anonymously leaked a NASA document to former Air Force General Donald Kutyna that indicated NASA was aware that cold temperatures could damage the rubber O-rings used to seal gases, a critical component of the solid rocket booster. General Kutyna cunningly conveyed that information to Feynman, the one member of the Commission most equipped to evaluate the evidence scientifically and the most insulated from political pressures.

When Rogers wanted to leave out of the final report a portion of Feynman’s findings that reflected poorly on NASA, Feynman threatened to withhold his signature. Rogers gave in, and Feynman’s work became an appendix to the official report. In sum, Feynman concluded that “the management of NASA exaggerates the reliability of its product, to the point of fantasy.”

Feynman found, among other things, that the risks of flying were far higher than NASA claimed because NASA management badly misunderstood the mathematics of safety protocols and rated mission safety thousands of times higher than their engineers did, encouraging unrealistic launch timelines and a tendency to underestimate flight risks.

Crucially, Feynman showed how NASA determined that previous success “is taken as evidence of safety” (as if not killing anyone after having driven drunk ten times were evidence that one could safely drive drunk), despite a clear showing and “warnings that something is wrong.” As Feynman explained, “[w]hen playing Russian roulette the fact that the first shot got off safely is little comfort for the next.” Indeed, “[f]or a successful technology,” Feynman concluded, “reality must take precedence over public relations, for nature cannot be fooled.”

This lesson is one that must be learned and re-learned. Note that a similar situation existed prior to the Apollo 1 accident. After NASA renewed its focus on safety, 19 years passed until the Challenger accident, after which 17 years passed until the Columbia accident.

This tragedy was not the result of a chaotic, seemingly random, low-frequency event. It was the result of an obvious and preventable error. In their book Blind Spots, Harvard’s Max Bazerman and Notre Dame’s Ann Tenbrunsel argue that the Challenger fiasco exploited inconsistencies in the decision-making mechanisms of the brain. NASA leadership failed because they did not view the launch decision in ethical terms focusing on the lives of the crew. Instead, they allowed political and managerial considerations to drive their decision-making.

Another major cause of the Challenger disaster was groupthink or, more specifically, the illusion of unanimity. Although the engineers recognized the risk of malfunction of the O-ring under freezing conditions, the manufacturer agreed with the launch of the Challenger owing to an illusion of unanimity. Skeptics did not feel empowered to speak up (raise your hand if you’ve been in a meeting where the leader “asks” for questions and qualifications but doesn’t really want to hear them).

I think another problem was involved, too.

As Diane Vaughn relates in her account of the tragedy, The Challenger Launch Decision, data were compiled the evening before the disastrous launch and presented at an emergency NASA teleconference, scribbled by hand in a simple table format. The table showed the conditions during each of the O-ring failures.

Some engineers used the chart as part of their argument to delay the mission, asserting that the shuttle’s O-rings had malfunctioned in the cold before, and might again. But most of the experts were unconvinced.

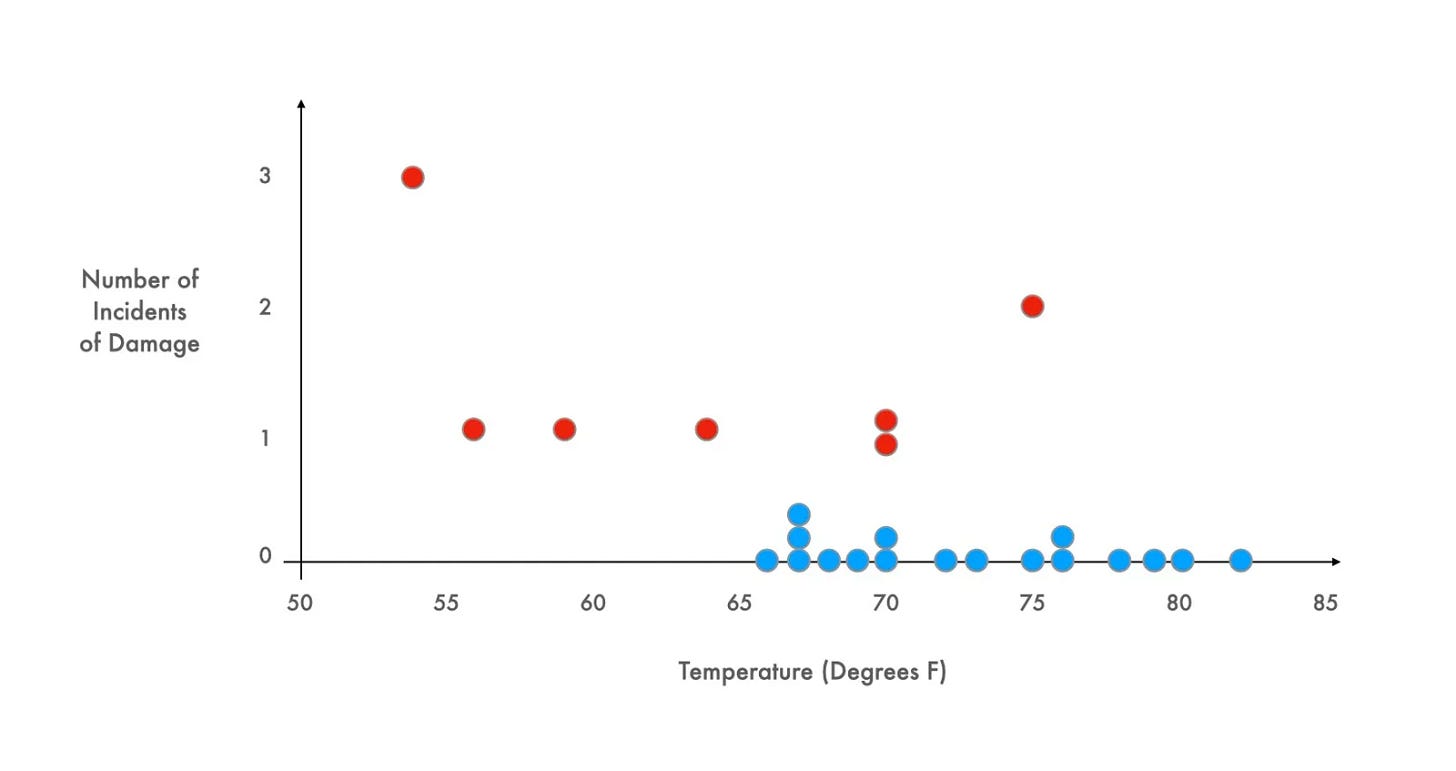

This information is used as part of a case study, too, in the guise of a racing team deciding whether to race in the cold, and has been used with students around the world for more than three decades. Most groups presented with this study look at the scattered dots on a graph like the one above and decide that the relationship between temperature and engine failure is inconclusive. Almost everyone chooses to race.

Almost no one looks at that chart, considers the situation, and asks to see the missing data – the data from those races which did not end in engine failure. Fatefully, nobody at NASA made that connection, either.

When the full range of data is presented, it becomes obvious that every success was above 65 degrees, and every use below 65 degrees ended in failure. Edward Tufte, the great maven of data visualization, used the Challenger decision as a powerful example of how not to display quantitative evidence. A better graph, he argued, would have shown the truth at a glance.

In essence, none of the relevant actors thought to invert their thinking.

The great 19th Century German mathematician Carl Jacobi, created this helpful approach for improving your decision-making process, popularized in the investment world by the late Charlie Munger: Invert, always invert (“man muss immer umkehren”).

Jacobi believed that the solution for many difficult problems could be found if the problems were expressed in the inverse – by working or thinking backward. As Munger explained, “Invert. Always invert. Turn a situation or problem upside down. Look at it backward. What happens if all our plans go wrong? Where don’t we want to go, and how do you get there? Instead of looking for success, make a list of how to fail instead – through sloth, envy, resentment, self-pity, entitlement, all the mental habits of self-defeat. Avoid these qualities and you will succeed. Tell me where I’m going to die, that is, so I don’t go there.”

As in most matters, we would do well to emulate Charlie. But what does that mean?

It begins with working backward, to the extent you can, quite literally. If you have done algebra, you know that reversing an equation is the best way to check your work. Similarly, the best way to proofread is back-to-front, one painstaking sentence at a time. But it also means much more than that.

The inversion principle also means thinking in reverse. As Munger explained it: “In other words, if you want to help India, the question you should ask is not, ‘How can I help India?’ It’s, ‘What is doing the worst damage in India?’”

If you want to know why companies succeed, consider why they fail. If you want to know how and why O-rings failed, you need to know when and how they worked as they should.

The smartest people always question their assumptions to make sure that they are justified. The data set that was provided the night before the Challenger launch was not a good sample. By inverting their thinking, flight officials might more readily hypothesize and conclude that the sample was lacking.

The inversion principle also means taking a step back (so to speak) to consider your goals in reverse. Our first goal, therefore, should not be to achieve success, even though that is highly intuitive. Instead, our first goal should be to avoid failure – to limit mistakes.

The best life hack is to avoid dying.

Instead of trying so hard to be smart, we should invert that and spend more energy on not being stupid, in large measure because not being stupid is far more achievable and manageable than being brilliant. In general, we would be better off pulling the bad stuff out of our ideas and processes than trying to put more good stuff in.

George Costanza has his own unique iteration of the inversion principle: “If every instinct you have is wrong, then the opposite would have to be right.”

Notice what Charlie wrote in a letter to Wesco Shareholders while he was chair of the company.

“Wesco continues to try more to profit from always remembering the obvious than from grasping the esoteric. … It is remarkable how much long-term advantage people like us have gotten by trying to be consistently not stupid, instead of trying to be very intelligent. There must be some wisdom in the folk saying, ‘It’s the strong swimmers who drown.’”

It is often said that science is not a matter of opinion but, rather, a question of data. That’s true, but largely aspirationally true because data must be interpreted to become useful or actionable, and fallible humans do the analysis.

We’d do the relevant analysis much more successfully if we’d invert. Always invert.

Totally Worth It

“Patience isn’t passive. It’s active.”

Feel free to contact me via rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or on Twitter (@rpseawright) and let me know what you like, what you don’t like, what you’d like to see changed, and what you’d add. Praise, condemnation, and feedback are always welcome.

Of course, the easiest way to share TBL is simply to forward it to a few dozen of your closest friends.

A Boston clarinetist, who died recently at age 85, used a middle-class income to build a fortune in the stock market, and gave away $125 million.

You may hit some paywalls below; some can be overcome here.

This is the best thing I’ve read recently. Infinite fringe. Five ways to spot a forgery. The Texas Lottery got played. Avoiding extinction. RIP, Pope Francis.

The late Val Kilmer: “God wants us to walk, but the devil sends a limo.”

Please send me your nominations for this space to rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or via Twitter (@rpseawright).

Benediction

Phil Keaggy provides this week’s benediction with some fantastic picking and singing.

We live on “a hurtling planet,” the poet Rod Jellema informed us, “swung from a thread of light and saved by nothing but grace.” To those of us prone to wander, to those who are broken, to those who flee and fight in fear – which is every last lost one of us – there is a faith that offers hope and love. And may grace have the last word. Now and forever. Amen.

As always, thanks for reading.

Issue 188 (April 22, 2025)

Superb.

I realized years ago, that for most industries, the winner wasn’t the most brilliant or perfectly executed, but the one who made the least mistakes. Sports too.

What a great and oh-so useful read. Thank you!!