Keeping Perspective

Putting 2022 market performance into context.

Legend has it that an ambitious young man once found himself in the presence of the legendary magnate, J. Pierpont Morgan. He ventured to inquire of Morgan’s opinion as to the future course of the stock market. The alleged reply has become a classic.

“Young man, I believe the market is going to fluctuate.”

Of course, nobody complains when markets fluctuate upward. It is only the downward fluctuations that bring distress.

The markets “fluctuated” in 2022. Keeping that outcome in perspective is the subject of this week’s TBL.

If you like The Better Letter, please subscribe, share it, and forward it widely. It’s free, and I never sell or give away email addresses.

NOTE: Some email services will likely truncate TBL. If so, or if you’d prefer, you can read it all here. If it is clipped, you can also click on “View entire message” and you’ll be able to view the entire post in your email app.

Thanks for visiting.

Keeping Perspective

Every January I publish an investment outlook as part of my day job. Doing so provides me with a great opportunity to look at the “big picture” – what happened in the just-ended year and the major themes I’ll be following in the markets and the world going forward.

By almost any measure, 2022 was lousy, at least from a market perspective. Here’s a picture.

January 3 was the first day of market trading for 2022. The S&P 500 hit another all-time high, after 70 record highs in 2021. At the time, it seemed like just another normal day in a rally that began shortly after Barack Obama was elected president and had continued, largely unabated, for over a decade.

As it turned out, that Monday, 2022’s opening day, was a tipping point. The S&P 500 had risen more than 600 percent since March 2009. During that time, investors were handsomely rewarded for buying stocks.

Not anymore.

The first day of trading in 2022 was the best day of trading in 2022. Stocks didn’t get that high again. It was the S&P’s high for the year. It was the NASDAQ’s high of the year.

Two days later, on January 5, the Federal Reserve released the minutes from its Open Markets Committee’s previous meeting, which disclosed that policymakers at the central bank were so worried about inflation that they thought they might need to accelerate how fast they raised interest rates.

The markets took the news badly, igniting a sell-off that was a precursor to the rest of the year. It was all downhill from there, and not in a good way. The reaction hit everything everywhere all at once. And it was hardly the only bad news.

The first major European war since the 1990s, unprecedented sanctions, energy-price mayhem, snarled supply chains, another year of Covid, bailouts, global interest rates rising at their fastest pace in four decades, the worst bond market ever, a faltering Chinese economy, an overheating American one, housing markets looking frothy across the rich world, and a crypto blow-up for the ages all contributed to a lousy year in the stock market.

More importantly, perhaps, the past 12 months have marked a generational shift for financial markets as the Fed repeatedly raised interest rates to try to contain the worst inflation in four decades. The Fed’s efforts have seemed to be working, if not as fast or as certainly as desired. However, the Fed’s aggressive actions to slow the U.S. economy, the world’s largest, have not been without consequences, far and wide.

The standard 60:40 portfolio (60% S&P 500: 40% 10T), long the primary benchmark for individual investors, declined 17.5 percent in 2022, as both components were big losers.

After a three-year winning streak, the S&P 500 lost 18.11 percent in 2022 – despite a 7.56 percent gain in the 4th quarter – and hasn’t made a record high since that opening day of the year. Per Morningstar, the average U.S. stock fund finished 2022 down roughly 17 percent, with the average large-value fund down about 6 percent, and large-growth funds down an average of nearly 30 percent.

Foreign equities were not immune to macro headwinds driven by the difficulties in the American markets.

Central banks use higher interest rates as their primary tool for combating inflation. When rates rise, borrowing costs increase, which tends to slow economic demand and temper inflation. The yield on the benchmark 10-year U.S. Treasury note, which underpins borrowing costs across the globe, after approaching 4.25 percent in late October, settled back to 3.88 percent at year-end, still a 2.36 percentage point annual increase, its biggest annual jump ever. In turn, borrowing rates on mortgages, loans, and bonds ratcheted higher.

The yield curve inverted – a common signal of pending recession – with rates for 5-year U.S. Treasury notes first exceeding those for 30-year bonds in March, while the gap between two and 10-year yields also flipped.

By most measures, domestic bonds suffered their worst year ever in 2022. The S&P U.S. Treasury Bond index lost 11 percent, long-term U.S. Treasuries lost 29 percent (by one measure), and the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond index declined 13 percent, its worst year since the index’s inception in 1977. Per Morningstar, U.S. core bond funds – strategies generally used as the basic building blocks of consumer portfolios – lost an average of roughly 12 percent in 2022, high-yield funds were down an average of about 9 percent, and inflation-protected bond funds lost some 8 percent.

The housing market is in decline, as well. The National Association of Realtors reported recently the median existing-home sales price in the U.S. was $370,700 in November — down from a record $416,000 in June, but up 3.5 percent from November 2021 – while sales of previously owned homes declined for the tenth straight month, down 35 percent year-over-year. Americans are spending down their pandemic savings while banks are tightening their lending standards.

The year-end 30-year FHLMC composite mortgage rate of 6.42 percent is the highest year-end level since 2001; the 3.3 percent increase in mortgage rates during 2022 was the largest annual rise on record.

Higher borrowing costs also mean lower profits for companies. S&P 500 company earnings are expected to have grown 5.1 percent in 2022, well below the average annual increase of 8.5 percent that Wall Street posted over the past 10 years, according to FactSet. Excluding energy, S&P 500 earnings would have fallen 1.8 percent this year.

Middling-to-miserable profits sent stocks sharply lower throughout the year. Global equity markets lost $33 trillion in value from their peaks. That problem proved especially true for tech companies, whose immense growth had largely been fueled by low interest rates.

More specifically, the “big tech” stocks had a lousy year in 2022. For example, Tesla dropped 65 percent, its worst annual performance since the company went public in 2010 and only the second year the stock has declined in value. TSLA founder Elon Musk lost over $200 billion in net worth. Perhaps worse, he bought Twitter.

As investors lost money in the stock market, and households faced ballooning costs from inflation, the air came out of other, more speculative markets as well. Some flagrant absurdities had screamed that something was wrong. A virtual yacht sold in the metaverse of an online game for $650,000, virtual real estate transactions in the metaverse totaled more than $500 million, and a digital Gucci handbag sold for $4,000, more than a real one, in the metaverse.

It couldn’t last … and it didn’t.

The price of Bitcoin, the best-known cryptocurrency, tumbled 65 percent, and so-called meme stocks like GameStop (-50%) and AMC Entertainment (-85%), fell throughout the year.

All told, the U.S. economy remained resilient, especially compared with the rest of the world. Europe faced an energy crisis. China faltered (-23%) amidst Covid-related shutdowns. The relative strength of the United States made it a safer place for global investors to put their money, and the influx of cash helped push the value of the dollar higher. In 2022, for the first time in 20 years, the dollar was worth more than the euro.

An unexpectedly dire report showing a collapse in consumer sentiment just days before the central bank was set to meet on June 15 spooked policymakers and helped send the S&P 500 into a bear market, defined as a fall of at least 20 percent from its recent peak – In this case, January 3, 2022.

The Fed had already raised interest rates twice, by a total of 0.75 percentage points – as much as the central bank had forecast as recently as December 2021 would be necessary for the entire year – and was gearing up for another rate increase, expected to be 0.5 percentage points. Instead, the Fed tightened by 0.75 percentage points for the first time in almost three decades, indicating the risks attributed to rising inflation.

Even so, these turbulent events led some traders to think that surely the worst was over. In July, as second quarter corporate earnings reports started coming in looking better than had been expected, the stock market rallied. From mid-June to mid-August the S&P 500 rose 17.4 percent.

That rally wasn’t sustainable.

Rising stock prices created a problem for the Fed by enriching traders and working against its efforts to lower inflation. Fed chair Jerome Powell sternly warned investors in August that the inflation fight was far from over and that interest rates would need to rise considerably before the central bank would end its tightening campaign. Stock markets heard him, began to fall again, and the S&P 500 hit another new low in October.

Still, as inflation began to moderate, stocks traded off their lows. The S&P has advanced 7.56 percent since October.

In December, the Fed increased interest rates to a target range between 4.25 and 4.5 percent – far above expectations at the start of the year. Policymakers also raised their forecasts for how high interest rates would need to rise in 2023, but traders have barely blinked. There are continued signs of cooling inflation, and some see a greater likelihood that the central bank will pause further rate increases sooner than it has indicated to allow the effects of the current rate levels to seep into the economy.

How this standoff between the bond market and the Fed plays out will go a long way toward telling us what 2023 will be like in the markets.

That said, many analysts expect corporate profit expectations to be revised sharply lower in early 2023, as prolonged inflation and elevated interest rates bite into earnings. That could mean that stocks have further to fall.

In sum, the Fed raised rates seven times in 2022, pushing its benchmark from a range of 0-to-0.25 percent to the current 4.25-to-4.50 percent, a 15-year high. Fed officials signaled in December that they expect to keep raising rates to between 5-and-5.5 percent in 2023.

The Conference Board’s collection of leading economic indicators has fallen for nine months in a row, reaching levels that have historically preceded recessions. Gauges that track overall business activity as well as the services and manufacturing sectors have fallen to some of the lowest levels since the brief, Covid-induced 2020 recession.

Wall Street analysts project economic growth for 2023 will slow to about 0.5 percent, on average, with Goldman Sachs the most optimistic, expecting one percent annual GDP growth. The economy grew at an average pace of 2.1 percent from 2012 to 2021.

Most of the economists recently surveyed by The Wall Street Journal expect these higher interest rates will push the unemployment rate from December’s 3.5 percent (the most recent data available) to above 5 percent – still low by historical standards, but that increase would still mean that millions of Americans lose their jobs.

Most also expect the U.S. economy to contract in 2023. That said, it is important to note that almost everyone on Wall Street and in Washington got 2022 wrong – from the Fed’s insistence that inflation would be transitory to top Wall Street analysts who projected a banal year of growth for stock and bond prices.

Last year brought the end to a 40-year period of ever-lower interest rates that made borrowing cheap and encouraged risk-taking – on stocks, in debt markets, on real estate, and even in cryptocurrencies – in a hunt for lucrative returns. TINA (“There Is No Alternative”) is dead.

In 2022, the S&P 500 suffered its worst annual performance since 2008. Technology stocks were hit especially hard. Debt is no longer cheap. Bonds got smoked. Real estate prices have dropped. Cryptocurrency giants like FTX have collapsed.

The bottom line: 2022 was a lousy year for the markets (look at the picture above, again). At least energy did well.

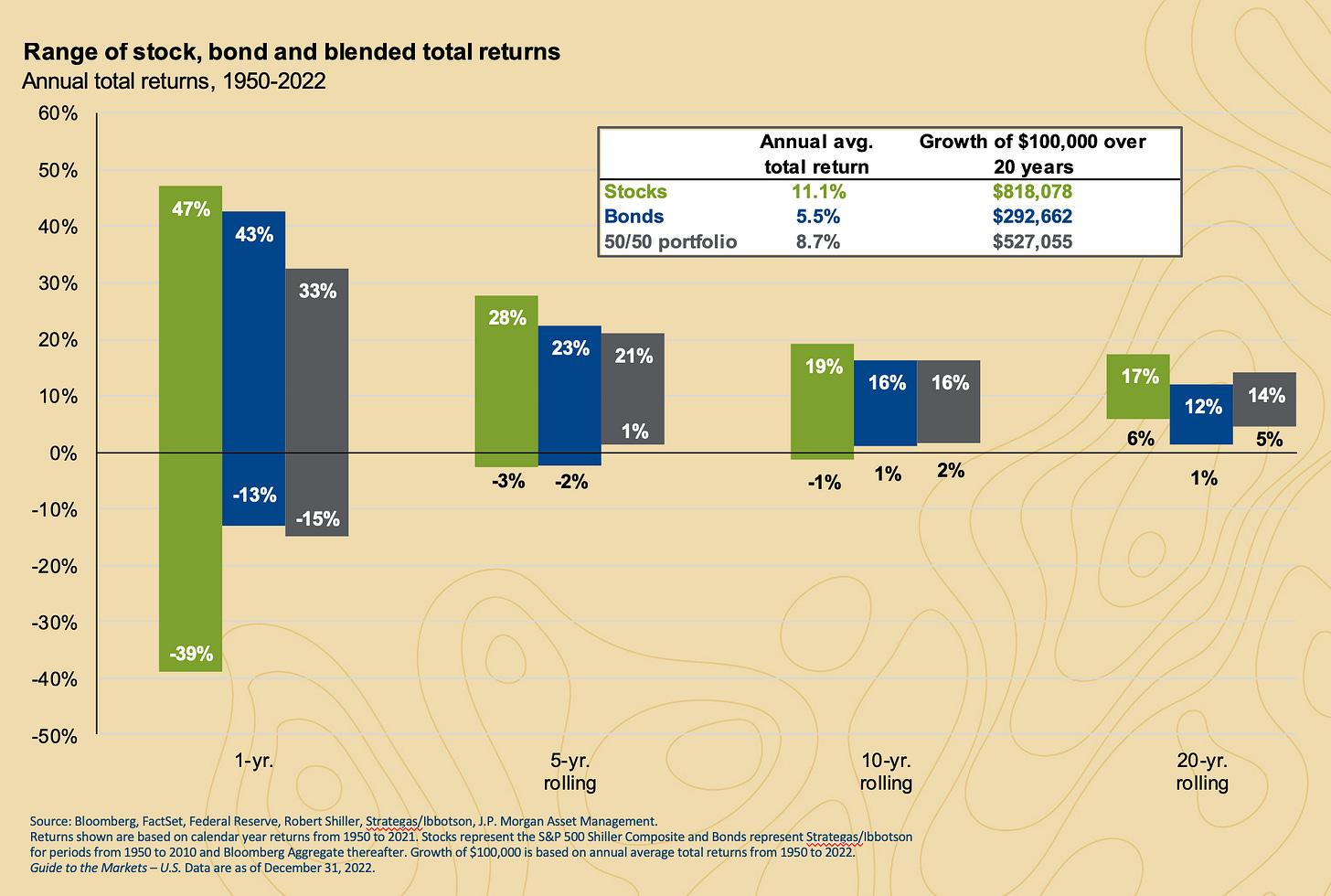

However, some context is in order. Getting from point A to point B is almost always messier than we expect. Drawdowns – like those we saw in 2022 – are the cost of the much higher returns generally offered by equities over time compared with other investment opportunities.

Long ago, Sir Isaac Newton discovered the three laws of motion, which were the work of genius. But Newton’s talents didn’t extend to investing. He lost a bundle in the South Sea Bubble, explaining later, “I can calculate the movement of the stars, but not the madness of men.” If he had not been so traumatized by this loss, he might well have gone on to discover the Fourth Law of Motion, formulated instead by Warren Buffett.

“For investors as a whole, returns decrease as motion increases.”

That’s why, so far at least, investing has always paid off over the long haul; 2022 was ugly but, in context, it was entirely normal.

More broadly, life is remarkably good for most of us. In many ways, the current world is a huge improvement over what came before. Statistically speaking, tribal warfare was nine times as deadly as war and genocide were even in the 20th century, despite its concentration camps, gulags, and killing fields. The murder rate of medieval Europe was more than 30 times what it is today. Slavery, excessive and sadistic punishments, and frivolous executions were unexceptionable features of life for millennia but are quickly disappearing today (if not nearly quickly enough).

Wars between developed countries have all but vanished and, even in the developing world, warfare kills at a fraction of the rate it did just a few decades ago. Rape, assault, hate crimes, deadly riots, child abuse and more are all substantially less common than they once were. Hunger has been more than halved in the developing world since 1990. Disease is waning dramatically, allowing most of us to live longer. Things are a long way from perfect and plenty of problems persist, but the overall picture isn’t half-bad. Not many of us would jump at the chance to switch places with those who lived during other eras.

Obviously, even a smidge of perspective shows how good I (and probably my readers) have it. Not a lot of destitute people read TBL, I’d wager.

We are all prone to self-serving bias – the idea that when good stuff happens to us, we deserve it or have earned it somehow, but the lousy stuff is just bad luck. However, as Cambridge’s John Rapley has shown, “economists who’ve actually worked out scientifically what contribution our own initiative plays in our success have found it to occupy an infinitesimally small share: the vast majority of what makes us rich or not comes down to pure dumb luck, and in particular, being born in the right place and at the right time.”

Steve Jobs’ life would have been pretty different had he been born into a Bengali peasant family.

Being human is itself an essentially impossible bit of luck. As my friend Morgan Housel explained: “reading this means you belong to the only species out of 8.7 million on this planet that can read. And our planet is the only one out of 100 billion in our galaxy that we know has life.”

Living now is also remarkably lucky. As Don Boudreaux wondered, it’s not obvious that you’d be better off if you were a billionaire 100 years ago rather than remaining solidly middle-class in America today.

I could have been born in the 7th Century. I could have been born in North Korea. I could have been born into a family that abused me (which is much more likely than I care to think). I could have had to struggle for even minor educational advancement. Duke could have been less generous with financial aid. My boss could be a jerk. My children could be disdainful. My grandchildren might never visit and hate baseball.

My wife could be a little less wonderful (although I doubt it). Nick Heil explained it very well: “you never really know how lucky you are until your luck runs out.”

As the Irish poet and playwright, Nobel laureate Seamus Heaney, wrote three decades ago, and as my wonderful bride shows every day: “History says, don’t hope on this side of the grave, but then, once in a lifetime, the longed-for tidal wave of justice rises up and hope and history rhyme.” For me, as I have written before, the rhyming is set to music.

All of which brings me to my key point.

A while ago, now, on my darling bride’s early January birthday, our entire family – three children, their spouses, and grandchildren – was together for a time of fun and general frivolity. We went out to breakfast and walked the beach in one of the world’s richest zip codes. It was a great day.

Later, while getting some coffee (decaf, of course) for my bride, we ran into a young woman with a sign announcing that she was a homeless single mother looking for help. She looked desperate, sad, and embarrassed by her situation. It’s possible that she was looking to scam us, but I doubt it. The look on her face seemed too real, too vulnerable, too visceral. I doubt she was that great an actress.

Just before the police forced her to move on, we were able to give her some money. Her eyes filled as she grasped my wife’s hand and kissed it while offering urgent and heartfelt thanks. We cried too and recognized that we almost surely got more benefit from our purported generosity than she did. Still, it was something.

For most of us here in the U.S., our lives are pretty good. By world standards they are pretty great. By historical standards they are downright spectacular. And for most of us who work in the finance business, life is especially good. We make up a highly disproportionate segment of those who make the most money, too. For lots of practical purposes, we are the one percent or at least a reasonable facsimile thereof.

I’m not making a political argument or even a Piketty point except to emphasize that there remain far too many people for whom the American Dream is not remotely plausible. I don’t mean those who are vaguely or not so vaguely dissatisfied with how their lives have evolved or who haven’t accomplished what they set out to. I’m not talking about American exceptionalism or the lack thereof. I’m not thinking in terms of Thoreau’s quiet desperation or of those who think that they have done everything “right” but that life has somehow welched on its end of the bargain, or even of those who “went to emergency” at the hands of Wall Street’s rapacious hellions even if and as none of the scalawags went to jail (with apologies to Don Henley).

I’m simply thinking about people like that poor mother, wondering how she might provide for her kids and hoping against hope that things might get just a little bit better. Nearly all of us that read (or write) TBL have been blessed beyond reasonable expectation and almost surely beyond our talent and effort [raises hand], 2022 notwithstanding. We need to do more, be more, and give back more.

It’s simply the right thing to do.

If you’re like I am, it’s far easier to lose empathy for those who are less fortunate than we’d like to think. We all want to believe that our achievements are all us and that our failures are someone else’s fault. But we are almost surely far less skilled than we assume and, even if not, Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle can get the better of us when we least expect it. Rain falls on the just and the unjust alike, as the Scripture says.

And everything can change in a New York minute.

So please, let’s all resolve to pay a bit more attention to those who could use a little or maybe a lot of help. Do it in a manner that is consistent with your conscience and your convictions. But please, don’t delay. A life may hang in the balance.

Totally Worth It

Feel free to contact me via rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or on Twitter (@rpseawright) and let me know what you like, what you don’t like, what you’d like to see changed, and what you’d add. Praise, condemnation, and feedback are always welcome.

Of course, the easiest way to share TBL is simply to forward it to a few dozen of your closest friends.

Not everybody read last week’s TBL: Forecasting Follies.

You may hit some paywalls below; most can be overcome here.

This is the best thing I read this week; this is the best thing I saw (the movie, not the trailer). The sweetest. The saddest. The loveliest. The prettiest. The funniest. The creepiest. The coolest. The most insightful. The most fascinating. The most profound. The most poignant. The most disappointing. The most remarkable. The least surprising. HUMAN_FALLBACK. Meeting customer needs. Shocking, if not surprising (one, two, three, and four). Excellent. Disgusting. Tipping point? Books as physical objects. Tone deaf. Minority opinion. Culture. If you’ve sat through one, you’ll know. San Diego’s happy lead story, broader context here. Smart thinking. No Planet B. RIP, Paul Johnson. RIP, Elaine Benz. RIP, David Crosby.

Please send me your nominations for this space to rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or via Twitter (@rpseawright).

This week marked the 30th anniversary of The Simpsons’ legendary Monorail episode, Alan Siegel caught up with Conan O’Brien, a former writer for the show, on what it was like to pitch what is now considered one of the most timeless bits in sitcom history. “ [“Marge vs. the Monorail”] warned the world about charismatic men selling foolishly grandiose solutions to problems that don’t need fixing,” Siegel writes for The Ringer. “References to the episode will never cease making O’Brien happy. While browsing the Rose Bowl flea market, his friend once noticed a framed travel poster showcasing Homer and the monorail. ‘It says, “Glides as smoothly as a cloud,’’’ O’Brien says. ‘I was like, “You have to buy that for me.” It wasn’t even that much. That’s hanging in my house, and I kind of smile every time I see it.’ Still, the fact that ‘Marge vs. the Monorail’ is seemingly brought up whenever a grifter dupes the public surprises O’Brien. After all, it was an idea that started very, very small.”

The TBL Spotify playlist, made up of the songs featured here, now includes nearly 250 songs and about 17 hours of great music. The TBL Christmas playlist is here. Whichever one you listen to, I urge you to listen in, sing along, and turn up the volume.

Benediction

To those of us prone to wander, to those who are broken, to those who flee and fight in fear – which is every last lost one of us – there is One who offers grace and hope. And may love have the last word. Now and forever.

Amen.

Thanks for reading.

Issue 138 (January 20, 2023)