The Better Letter: Working Hypothesis

TBL is back to take a look at the great arc of economic history.

In a terrific feature this week on Dusty Baker, Darren Lewis shared some advice Baker had offered about “surveying the land” in baseball.

“‘Darren, when you go up to the plate, do you look around?’ And I said no. He said, ‘Survey the land … You need to survey the land. Look, the center fielder is playing over there, and the left fielder is over here. So this is how they’re going to pitch you.’”

My dad shared that outlook. He emphasized getting “the lay of the land,” and meant it both literally and figuratively.

In this week’s TBL return, I’m going to describe the lay of the land, as I see it – my working hypothesis for the way things are in a sweeping take on economic history and how we got to now.

If you like The Better Letter, please subscribe, share it, and forward it widely.

I missed time here for a variety of reasons related to family health, work, other projects, and inertia. But, I’m back, if not every week. Thank you for sticking with me.

All the charts in this week’s TBL mean that some email services will truncate it. If that happens, or if you’d prefer, you can read this edition of TBL here. If it is clipped, you can also click on “View entire message” and you’ll be able to view the entire post in your email app.

Working Hypothesis

The sweep of economic history, at least in the Global North, seems to be explained by a series of great revolutions.

Beginning in what we call pre-history, a neolithic revolution began to move humanity from roving bands of hunters and gatherers toward civilization and settlement, using agriculture and the domestication of animals.

During the Middle Ages, a commercial revolution (circa 1200ff.) drove the creation of a European economy based on trade.

The Protestant Reformation (1517ff.) induced a widespread religious, cultural, and social upheaval in Europe that broke the hold of the medieval Church, allowing for the development of personal interpretations of Christianity, clearing space for the rise of secular science and capitalism, and leading to the development of modern nation-states.

A scientific revolution (1543ff.) invoked developments in mathematics, physics, astronomy, biology (including human anatomy), and chemistry to transform the views of society about nature and replace the Greek view that had dominated science for almost 2,000 years. It provided “the transition from an implicit trust in the internal powers of man’s mind to a professed dependence upon external observation; and from an unbounded reverence for the wisdom of the past, to a fervid expectation of change and improvement.”

An industrious revolution (circa 1600ff.), inspired by the Protestant work ethic, transformed commerce. Household productivity and consumer demand increased during this period despite the absence of major technological innovations that would mark the later Industrial Revolution.

By way of a democratic revolution (1688ff.), a new system of government came to the fore, one that provided a systematic rule of law and “which admits no right of government except that arising from the free consent of those who submit to it, and which maintains that all persons who take part in government are accountable for their actions.”

The Industrial Revolution (circa 1760ff.) was a process of change from a largely agrarian and handicraft world economy to one dominated by industry and machine manufacturing. These technological changes introduced novel ways of working and living and fundamentally transformed society.

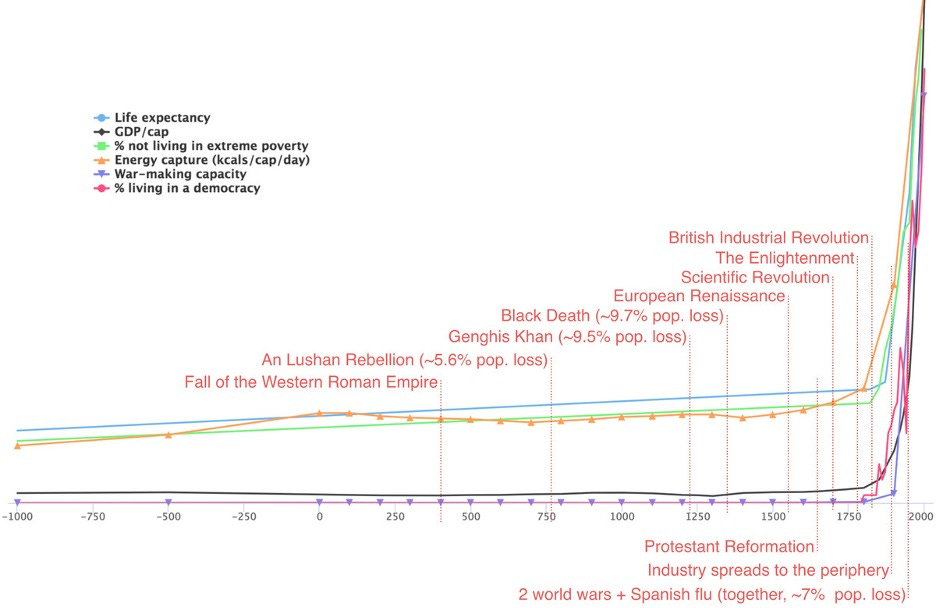

But here’s the thing. The big transformation of lives from antiquity through today – and the size and impact of it cannot be overstated – was on a time delay despite these “revolutions.” In terms of the very big economic picture, the world only began to change around 1870.

Roughly then. Give-or-take.

There is nothing particularly noteworthy about 1870.

There is also no clear explanation why this transformation didn’t happen sooner. For example, democracy dates to the ancient Greeks. And by 50 CE, Hero of Alexandria had invented the first vending machine, the first syringe, the first wind-powered machines, and a primitive rotary (reaction) steam engine, sixteen hundred years before impulse steam turbines were invented by Giovanni Branca and John Wilkins.

Modernity was slow in arriving.

Note this astonishing line from the seventh and final edition of John Stuart Mill’s classic, Principles of Political Economy, published in (wait for it) 1870: “Hitherto it is questionable if all the mechanical inventions yet made have lightened the day’s toll of any human being.”

However.

Beginning around 1870, sustained rapid economic and technological development unlike anything yet seen became the norm. Each succeeding generation found itself living in what seemed like a whole new world, utterly transformed from the world into which its parents had been born and, perhaps, utterly transformed from the world into which *they* had been born.

As Don Boudreaux wondered, it’s not obvious that you’d be better off if you were a billionaire 100 years ago (much less 150) rather than remaining solidly middle-class in America today.

The revolution came and it has been spectacular, at least from an economic perspective.

The economic transformation has been comprehensive. Yet, there is no event to initiate it – no invention of the steam engine, no 97 theses, no Glorious Revolution, no On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres – only our ability to observe and describe it. It all seemed to just happen.1

Let’s look at the data.

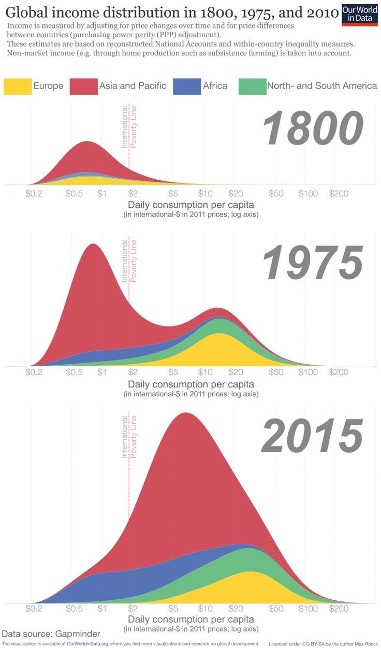

Income was flat for most of recorded history. Until.

After 1870, income and GDP began an exponential rise.

Before 1870, the world was stuck in a vicious cycle. Birth rates and death rates remained in rough equilibrium (the average woman had two surviving children) overall. Birth rates increase with income and death rates decline as income goes up. However, income goes down as population increases. Then, things start to get better. A lot better.

Everybody started living longer. A lot longer.

Democracy became a thing.

Literacy went from being the sole province of the rich to being commonplace.

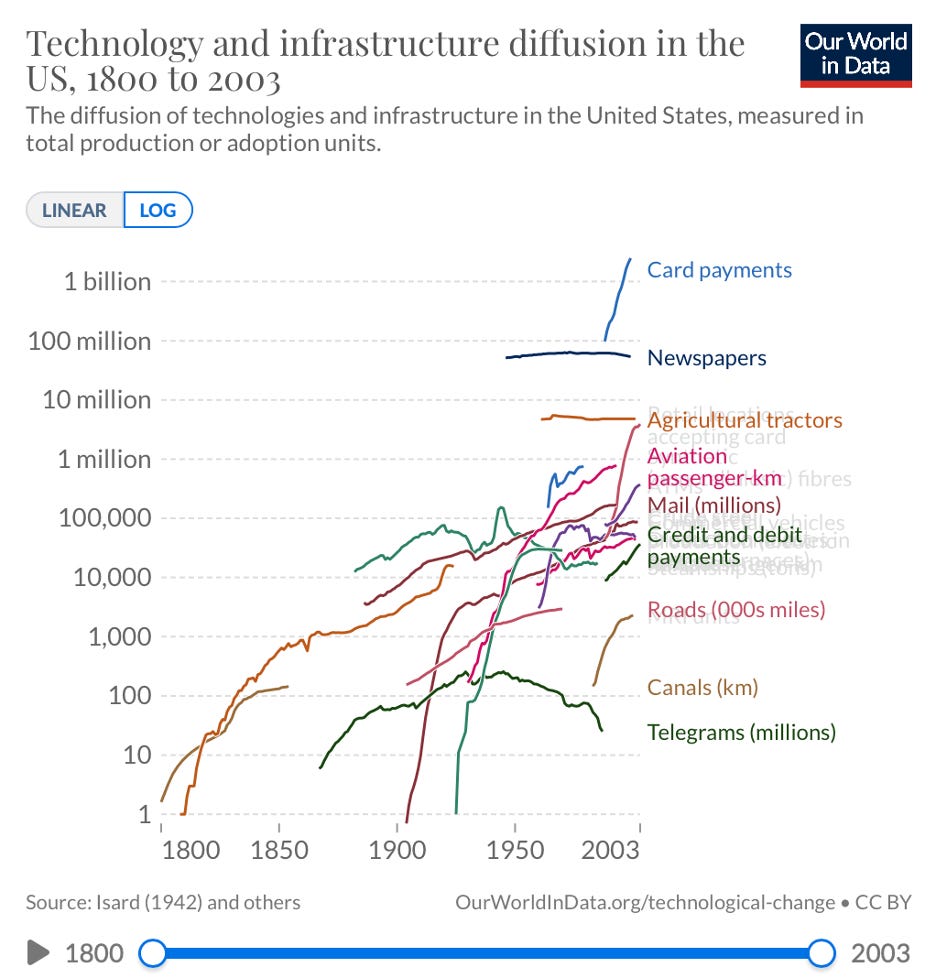

Technology exploded.

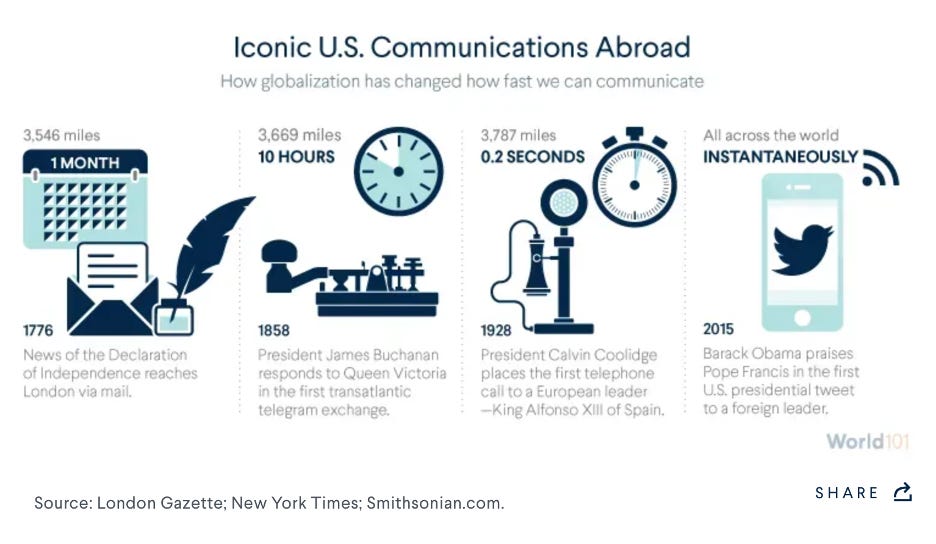

Communication became ubiquitous.

This massive transformation, which involved an historical shift from high birth rates and high death rates in societies with minimal technology, education (especially of women), and economic development, to low birth rates and low death rates in societies with advanced technology, education, and dramatic economic development, can only be described as a demographic revolution (1870ff.).

There is just no clear explanation why.

The inflection point in the available data with respect to measures of improvement came millennia after the invention of democracy, centuries after the emergence of capitalism, and decades after the advent of manufacturing at scale.

The Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz has argued that worldwide standards of living began to improve and continued to improve thereafter for two primary reasons: the development of science and developments in social organization, most prominently the growth of free-market economies and the rule of law. Significantly, science and the rule of law both include carefully derived and articulated systems and methods of assessing and verifying reality and what it means.

I don’t think Stiglitz is wrong, but my working hypothesis is it’s broader than that.

The development of science, democracy and its rule of law, the creation of global markets, and even the Reformation meant that truth was no longer something decreed from on high. To be guarded.

Truth thus became something to be discovered, tested, contested, and used. From the bottom up. Crucially, it became ascertainable, accessible, actionable, and accountable.

Before the scientific revolution, knowledge was dominated by the ancients. The concept of truth came from the “top down” and was based upon authority, such as that of Aristotle, Galen, or the Church. Accordingly, it was widely believed that all the most important knowledge was already known. Thus, learning was predominantly a backward-facing pursuit, about returning to ancient first principles, not pushing into the unknown.

The great innovation of science was that it built its concept of truth from the “bottom up,” with its principles discovered rather than pronounced. Truth became ascertainable, accessible, and actionable. Testing and retesting provide accountability.

Democracy gives us the rule of law and a system that protects all citizens, not just those with power and privilege. It includes a rigorous system for ascertaining what is true. Cross-examination makes truth accessible. Falsehoods are punished directly (perjury) and indirectly (through impeachment of witnesses and verdicts), providing accountability.

Free global markets do not test reality directly. But a new product that works better than existing products can garner capital, sales, and profits, making such “truth” actionable. And false claims generally indicate a poor product and lead to fewer sales, providing accountability.

According to Oxford’s Alister McGrath, Christianity’s “dangerous idea” came from Martin Luther: that individual believers could and should read the Bible for themselves and come to their own conclusions about what it means. Here, too, truth became ascertainable, accessible, and actionable. In this context, God provides accountability.

It is the *interaction* among ideas and events that matter over the long-run, and such interactions manifest themselves differently in different contexts. Accordingly, this new approach to truth didn’t take hold and alter behavior right away.

Ideas need to marinate with other ideas and then cook within the stew of the lives and experiences of people to inspire and nourish change and, eventually, as from and after 1870, transformative economic change.

Truth is a wildly powerful thing – strong enough to set us free. And enrich our lives.

Totally Worth It

Note this small ad taken from Oklahoma City’s local newspaper, “The Oklahoman,” recently.

Feel free to contact me via rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or on Twitter (@rpseawright) and let me know what you like, what you don’t like, what you’d like to see changed, and what you’d add. Praise, condemnation, and feedback are always welcome.

This is the best thing I read last week. The stupidest. The saddest. The snarkiest. The sweetest. The loveliest. The craziest. It’s possible. M*A*S*H is 50. Remarkable resolve. Hero.

Don’t forget to subscribe and share TBL. Please.

Of course, the easiest way to share TBL is simply to forward it to a few dozen of your closest friends.

Please send me your nominees for this space to rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or via Twitter (@rpseawright).

The TBL Spotify playlist now includes more than 225 songs and about 16 hours of great music. I urge you to listen in, sing along, and turn up the volume.

Benediction

This week’s benediction comes from the Hillbilly Thomists, who are really a thing and are terrific.

Amen.

Thanks for reading.

Issue 122 (September 23, 2022)

For Brad DeLong and his fascinating new economic history of the “long” Twentieth Century (1870-2010), the tipping point comes with the development of the vertically integrated corporation, the industrial research lab, modern communication devices, and modular shipping technologies. “The industrial research lab rationalized and routinized the discovery and development of technologies; the corporation rationalized and routinized the development and deployment of technologies; and globalization diffused them everywhere.” Those are indeed significant developments, but hardly the stuff of revolution.

This is a great piece and explanation for the Great Human Uplift is fundamental to economics which is just not a part of the core questions in economics. I found the work of Deirdre McCloskey worth studying. Her 3 volume opus on bourgeois values is a critical piece to story and interesting reading. The 1870's point focuses on the development of the big corporations, but the development and celebration of the entrepreneur, shopkeeper, merchant, and inventor is also critical and starts the process for growth.

So glad to have you back