Forecasting Follies

We can't predict the future. At all.

In the early 1980s, cellular phone service became reality. Handsets were huge, calls were staticky, data services non-existent, and coverage limited.

Still, it was never hard to imagine the possible benefits. So, AT&T asked McKinsey, the world’s top management consultancy, to estimate the future market size for this product. The forecast: the U.S. mobile phone market would approach 900,000 subscribers by 2000.

Not quite.

The first phone, the cement brick-sized Motorola DynaTAC, cost $3,995 in 1984. However, the core components got cheaper every year, and phones did too. They also got smaller and better. By the year 2000, you could find a new cellphone for a couple hundred bucks.

Networks were expanding, too. By 1991, mobile networks were introducing data services, albeit s-l-o-w-l-y. Had digital cameras been a thing at the time, sending a single photo would have taken several minutes. By 2020, common 4G phone networks were more than 3,000 times faster. Mobile tariffs collapsed in line with the growing speed of the networks. Between 2005 and 2014, the average cost of delivering one megabyte of data, the equivalent of about 150,000 words, dropped from about $8 to pennies.

Here’s the bottom line: McKinsey was way off. In the year 2000, more than 100 million Americans owned a mobile phone. The most storied management consultants in the world were wrong by a factor of 100 (and then some).

The McKinsey forecast was outlandishly, but not surprisingly, wrong.

As Daniel Kahneman, the world’s leading authority on human error, has carefully explained, “The idea that the future is unpredictable is undermined every day by the ease with which the past is explained.” So, it remains unpredictable, but lots of folks are going to try anyway.

Every year at about this time, I outline the previous year’s load of terrible forecasts. Because bad predictions are the norm, the only part that’s hard is narrowing down the list of misses to use. Unless you made any of the predictions outlined herein, I trust you will enjoy this year’s edition of Forecasting Follies.

The above is from Jason’s brilliant book, The Devil’s Financial Dictionary.

If you like The Better Letter, please subscribe, share it, and forward it widely. It’s free, and I never sell or give away email addresses.

NOTE: Some email services will likely truncate TBL. If so, or if you’d prefer, you can read it all here. If it is clipped, you can also click on “View entire message” and you’ll be able to view the entire post in your email app.

Thanks for visiting.

Forecasting Follies 2023

In September of 2021, as President Joe Biden’s Build Back Better plan was being considered by Congress, many worried about the inflationary pressure of injecting an additional $2.4 trillion into the economy in addition to the $4.1 trillion previously committed in response to the pandemic. Inflation was already hot. The August CPI report, issued September 17, showed that the inflation rate over the previous 12 months was 5.3 percent.

When it appeared that there were enough deficit hawks among Democrats to join with Republicans and scuttle the bill, economist and Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz rounded up another 16 (of 36) living American Nobel Prize winning economists to assuage those fears in via open letter. Stiglitz insisted, “the inflationary impacts will be at most negligible.”

By June 2022, inflation topped 9 percent and remains at 6.5 percent. That’s hardly negligible.

Between 2001 and 2006, renowned economist Lawrence Summers, winner of the 1993 John Bates Clark Medal and then president of Harvard University, entered into a series of forward swap contracts on behalf of Harvard’s endowment with Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan, and other big banks — contracts that eventually cost the university an estimated $1 billion in losses. The contracts were based upon Summers’ macro-economic forecast, which turned out to be wildly wrong. He thought that interest rates were low and sure to rise in the coming years. Instead, after the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, we entered a period of ultra-low interest rates from which we are only now emerging.

In 1998, the then-future Nobel laureate Paul Krugman made a remarkable and erroneous prediction: “By 2005 or so, it will become clear that the Internet’s impact on the economy has been no greater than the fax machine’s.”

The size of the digital economy has now reached $2.4 trillion annually.

Irving Fisher, the most famous economist of his day, forecast a permanently rising stock market just two weeks before the 1929 crash. Nobel laureate Paul Samuelson held fast to his futile prediction that the Soviet economy would flourish under Marxism for nearly three decades. And, in 2007, Alan Greenspan foresaw double-digit interest rates to combat an inflationary surge that is only becoming real 16 years later.

Then, there’s Long-Term Capital Management, its Nobel laureates, and its spectacular missteps and implosion.

Obviously, economic forecasting skill eludes even Nobel laureates and other eminent economists. As ever, humans – even really smart and savvy humans within their areas of expertise – are truly lousy at predicting the future. Still, we keep expecting to be able to. “The idea that the future is unpredictable is undermined every day by the ease with which the past is explained,” Daniel Kahneman (ironically, himself a Nobel laureate and signer of the Stiglitz missive) wrote in Thinking, Fast and Slow.

As I describe every year at about this time, the examples of poor forecasts and predictions are legion. The economy, the markets, and the world-at-large provide unlimited fodder for bad forecasts.

Despite our lack of talent at it, we humans are obsessed with prediction. (“Martians land on Earth. What does that mean for the market?”)

We all tend to suffer from what psychologists call hindsight bias, which makes us think we had predicted the future all along, that what happened was inevitable, and everybody should have seen it coming. But it’s a fraud.

As the mathematician Alfred Cowles observed decades ago, people “want to believe that somebody really knows.”

Nobody does.

As John Kenneth Galbraith succinctly (and correctly) stated, “There are two kinds of forecasters: those who don’t know, and those who don’t know they don’t know.” Stock market forecasts prove its truth year after year.

As Kahneman emphasized, “Claims for correct intuitions in an unpredictable situation are self-delusional at best, sometimes worse.”

It happens anyway.

Every December, Wall Street denizens saddle-up and produce seemingly earnest, highly specific forecasts for where the S&P 500 will be at the end of the next calendar year. With inflation moderating but still soaring, the Fed raising interest rates more slowly, but raising them nonetheless, Russia’s slog of a war in Ukraine, China’s decision to drop its “zero Covid” policy, a recession deemed all but certain in Europe and increasingly likely in the United States, a clear picture of what the future holds would be most welcome right about now.

However.

Beginning nearly a century ago, Cowles began looking at the market forecasts of the time and kept finding them wanting.

As outlined in his Expert Political Judgment, Wharton’s Philip Tetlock looked at 82,361 economic and political forecasts by 284 experts between 1987 and 2003. These experts made a living “analyzing” and pontificating on political and economic developments. He concluded that chimpanzees throwing darts at a board full of predictions would be more accurate than these alleged experts.

The CXO advisory group analyzed 6582 market forecasts by 68 experts from 2005 through 2012. The average accuracy was just 46.9 percent, worse than a coin flip.

As of 2020, the median Wall Street market forecast since 2000 missed its target by an average of 12.9 percentage points per year. The extent of that error over two decades was more than double the average annual performance of the stock market. The consensus forecast for 2021 missed by a whopping 25 percentage points.

Spoiler Alert: They haven’t improved since.

Twelve months ago, after three big years in a row, Wall Street’s forecasters called for another good year. The consensus estimate was that the S&P 500 would reach 4,825 as of the end of 2022. According to a Bloomberg aggregation of forecasts, even the most pessimistic prediction for the S&P 500 at that time — made by Mike Wilson of Morgan Stanley — thought the index would finish the year 10 percent higher than where it ended.

Marko Kolanovic, JPMorgan Chase’s co-head of global research, was convinced the Federal Reserve would go very slow with its plan to raise interest rates even though inflation had already soared to its highest level in four decades. The rate increases, he forecast, would come in increments so small that financial markets would barely feel them. Accordingly, he predicted a broad rally, expecting the S&P 500 to reach 5,050 by the end of 2022.

The year’s closing level was 3,839.

The Federal Reserve wasn’t any better. The Fed famously expected 2021’s inflation surge to be transitory. It wasn’t.

Core inflation climbed to a four-decade high in the fall, nearly tripling the Fed’s full-year forecast, and still sits at 6.5 percent, far above the Fed’s 2 percent target. At this time last year, the central bank saw 2022 ending with interest rates hovering around 0.3 percent. That turned out to be off only by a factor of 15 as policymakers raised interest rates from near-zero at the start of 2022 to 4.5 percent in December.

Fed officials, analysts, economists, and other forecasters are no better at predicting inflation than at predicting anything else: They stink at it.

Fund managers were also wrong, seeing inflation as transitory, expecting Fed tightening to be moderate (1-2 times), and overweighting equities. There are 865 actively managed stock mutual funds domiciled in the U.S. with at least $1 billion in assets. On average, they lost 19 percent in 2022. For example, Cathie Wood’s ARK innovation ETF lost 67 percent (she also called for deflation). Hedge funds got hammered, too.

And, over its full life, Jim Cramer’s Action Alerts Plus portfolio badly underperformed the market.

As ever, unable to see the future, the vast majority of funds underperform their benchmarks.

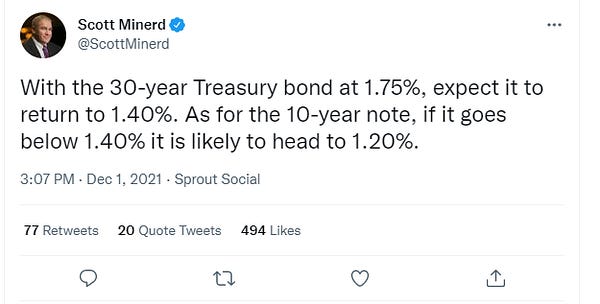

In terms of fixed income — a universe of 200 funds of a similar size — the average decline was 12 percent. For example, Ken Leech, Western Asset Management’s chief investment officer, was also convinced the Fed was in no hurry. In late 2021, he predicted there might not be any rate hikes at all in 2022. His firm’s largest bond fund, a $27 billion behemoth, lost 18 percent last year.

In December of 1994, Orange County, California, filed for bankruptcy protection after Robert Citron, its chief investment officer, lost billions of dollars speculating on fixed income derivatives betting that interest rates would not rise. When asked (a year earlier) why this wasn’t risky, Mr. Citron intoned, “I am one of the largest investors in America. I know these things.”

He didn’t.

Predicting market performance is much more a matter of luck than skill.

Bankers, meanwhile, doled out tens of billions of dollars in 2021 loans to private-equity firms that have since plummeted in value. Oops.

Now, let’s revisit the economists (“econo-misseds”).

Last year, economists surveyed by Bloomberg expected the PCE core index (“the Fed’s favored inflation gauge”) to fall to 2.5 percent by the end of 2022. They missed by roughly 100 percent.

In 2019, Bloomberg analyzed 3200 country-level economic forecasts by the IMF.

“In 6.1 percent of cases, the IMF was within a 0.1 percentage-point margin of error. The rest of the time, its forecasts underestimated GDP growth in 56 percent of cases and overestimated it in 44 percent.”

In December of 2021, the economists of the Mortgage Bankers Association forecast 30-year fixed rate mortgages in Q4 2022 at 4 percent and 10-year U.S. Treasury note yields at 2.3 percent. As of the start of 2023, 30-year mortgages (FHLMC) were at 6.48 percent (down from north of 7% in Q4) and the 10T yielded 3.79 percent. Those are big misses.

Wall Street analysts aren’t any better (updated here).

“It is commonly suggested that one group of informed participants, security analysts, may have some ability to predict growth. ... Over long horizons, however, there is little forecastability in earnings, and analysts’ estimates tend to be overly optimistic.”

Nobody knows what’s going to happen. We can guess, of course, and we might have a feeling (“Everybody had a hard/good year”)…

…but anyone who claims more certainty than that is delusional.

The “amateurs” trading meme stocks and cryptocurrencies – and losing tons of money – don’t look so out of place in that context, do they?

Narrator: “Bitcoin closed 2022 at 16,517.”

Experts routinely make bad predictions within their areas of purported expertise, as when, in 2017, then Federal Reserve Chair (and current Treasury Secretary) Janet Yellen said she doesn't believe another financial crisis will occur “in our lifetimes.”

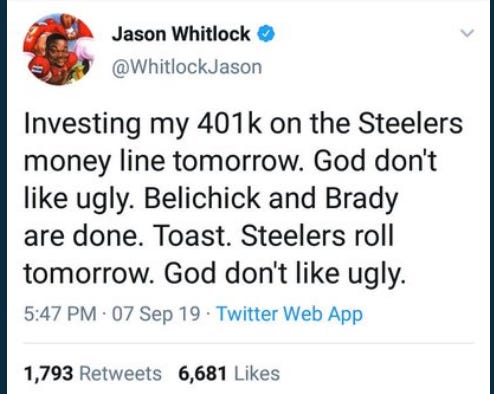

If anything, it’s even worse outside their supposed expertise.

Truth be told, bad forecasting is utterly human and, perhaps more dangerously (as my friend Jason Zweig continues to demonstrate), we misremember our forecasts – thinking they were a lot better than they were.

Nobody can know what’s going to happen. It’s physics’ three-body problem applied to the global economy’s trillions of inputs. There are far too many variables for forecasting to be a viable endeavor. We ought to be highly skeptical (or worse) of any prediction made about complex systems.

As ever, bad predictions aren’t limited to the world of finance. Vladimir Putin misread Ukraine, the CIA (and Joe Biden) misread Afghanistan, and Xi Jinping misread Covid.

There are, if anything, even more bad political predictions than market predictions, most likely because the “predictions” are designed more to appeal to the base or goose ratings – using some combination of wishful thinking and motivated reasoning – than to predict the future (which is not to say that market forecasts aren’t designed to foster new business, either).

Of the 31 ESPN baseball “experts” who predicted MLB playoff results, only four thought my San Diego Padres would beat the New York Mets in the Wild Card Series and not a single one predicted the Pads would eliminate the Los Angeles Dodgers in the Division Series.

None of them picked the Philadelphia Phillies to advance to the World Series, either.

Mike Trout was seen as having “D” potential. Vin Scully watched Sandy Koufax try-out for the Brooklyn Dodgers and thought, “No chance.”

“He doesn’t have the upside of (Ricky) Rubio,” college basketball analyst Doug Gottlieb said of Steph Curry, so far an eight-time All-Star, two-time Most Valuable Player, All-Star Game MVP, Finals MVP, and a four-time NBA champion. “(Brandon) Jennings, (Johnny) Flynn, (Patty) Mills, Teague all more athletic.”

As my friend Morgan Housel has explained, “Every forecast takes a number from today and multiplies it by a story about tomorrow.” We might have good current data, but “the story we multiply it by is driven by what you want to believe will happen” and what you’ve decided makes the most sense. Usually, the best story wins, correlation to reality not required.

Kahneman highlights the “illusion of understanding” – our predisposition to concoct stories from the information we have on hand. “The core of the illusion is that we believe we understand the past, which implies that the future should also be knowable.”

It isn’t.

The Economist – a magazine I admire – publishes an annual forecast of the year ahead. Its January 2020 issue does not mention a single word about Covid. Its January 2022 issue does not mention a single word about Russia invading Ukraine. That’s not a criticism – both events were impossible to know when the magazines were written. But that’s the point. The biggest news, the biggest risks, and the most consequential events are always what you don’t see coming.

History is driven by surprising events while forecasting is driven by predictable ones. Let the great Peter Bernstein explain more precisely (Peter L. Bernstein, “Forecasting: Fables, Failures, and Futures – Continued,” in Economics and Portfolio Strategy, November 15, 2002, p. 5).

“The very idea that a forecaster can spin a bunch of outcomes whose probabilities add up to 100 percent is a kind of hubris. Risk means that more things can happen than will happen, which in turn means that the scenarios we spin will never add up to 100 percent of the future possibilities except as a matter of luck. Like it or not, the unimaginable outcomes are the ones that make the biggest spread between expected asset returns and the actual result.”

As Jason Zweig put it, “The only true certainty is surprise.”

We miss the shocking “black swan” events, and that’s necessary, even appropriate, because they are, by definition, unforeseeable. However, we also miss “dragon-king” events – which, by understanding and monitoring their dynamics, some predictability may be obtained despite their outlier status. We even miss “gray rhino” events, “dangerous, obvious, and highly probable” occurrences that we should see lumbering toward us but usually don’t. Our failures in this regard should encourage us to prepare rather than predict and, perhaps, to try to limit our exposure to extreme fluctuations.

If only.

“No matter how much we may be capable of learning from the past,” Hannah Arendt wrote, “it will not enable us to know the future.”

In practical terms, per Kahneman, “The world is incomprehensible. It’s not the fault of the pundits. It’s the fault of the world. It’s just too complicated to predict. It’s too complicated, and luck plays an enormously important role.”

We will never act with perfect foresight. We will rarely act with decent foresight. Living with uncertainty, after all, “remains the essence of the human condition.” We will always have to navigate challenging and changing conditions, relying on experience, training, instinct, and imperfect assumptions, prone to our old familiar flaws (chiefly, “our never-failing propensity to discount the future”). This may not be an inspiring conclusion, but it is how the world works.

Totally Worth It

“I cannot forecast to you the action of Russia,” said Winston Churchill, at that time in England’s political wilderness, on the news that Stalin’s Soviet Union had signed a non-aggression pact with Hitler’s Germany. “It is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.” Churchill was right about the USSR and right about forecasting in general.

Feel free to contact me via rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or on Twitter (@rpseawright) and let me know what you like, what you don’t like, what you’d like to see changed, and what you’d add. Praise, condemnation, and feedback are always welcome.

Of course, the easiest way to share TBL is simply to forward it to a few dozen of your closest friends.

Note this powerful Churchill observation, eulogizing Neville Chamberlain.

“At the lychgate we may all pass our own conduct and our own judgments under a searching review. It is not given to human beings, happily for them, for otherwise life would be intolerable, to foresee or to predict to any large extent the unfolding course of events. In one phase men seem to have been right, in another they seem to have been wrong. Then again, a few years later, when the perspective of time has lengthened, all stands in a different setting. There is a new proportion. There is another scale of values. History with its flickering lamp stumbles along the trail of the past, trying to reconstruct its scenes, to revive its echoes, and kindle with pale gleams the passion of former days.”

You may hit some paywalls below; most can be overcome here.

This is the best thing I (re)read this week and the best thing I read in all of 2022. This is the best new thing I read this week. The smartest. The saddest. The coolest. The butteriest. The funniest. The most creative. The most inspiring. The most full of dread. The most daunting. The most unexpected plot twists. The least scientific. The least convincing. Feature or bug? Left-digit bias. Somebody’s got to do it. Climate change bet. Joy Reid embarrasses herself. The Southwest debacle, explained. El Ingeniero. RIP, Adolfo Kaminsky. RIP, Jeff Beck.

Please send me your nominations for this space to rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or via Twitter (@rpseawright).

Leo Tolstoy was a retired Russian military officer who fought in the Crimean War and was on hand for the siege of Sevastopol in 1854-55. His War and Peace describes the chaos of battle. The commands of the generals on both sides of the Napoleonic war he chronicles “were seldom carried out, and then only partially. For the most part the opposite happened to what they enjoined. Soldiers ordered to advance fell back on meeting grape-shot; soldiers ordered to remain where they were, suddenly, seeing an unexpected body of the enemy before them, would turn tail or rush forward, and the cavalry dashed unbidden in pursuit of the flying Russians.” Orders everywhere, Tolstoy wrote, “fell victim to the fear of death and a blind stampede in all directions.” War, according to Tolstoy, is marked by disarray, randomness, and uncertainty.

At least in the early days of the war, television analysts of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine hadn’t learned that lesson nor the power of a people fighting desperately for their homeland and their survival against a conscripted and indifferent enemy.

The TBL Spotify playlist, made up of the songs featured here, now includes nearly 250 songs and about 17 hours of great music. The TBL Christmas playlist is here. Whichever one you listen to, I urge you to listen in, sing along, and turn up the volume.

Benediction

Strong Son of God, immortal Love,

Whom we, that have not seen thy face,

By faith, and faith alone, embrace,

Believing where we cannot prove.

…

Our little systems have their day;

They have their day and cease to be:

They are but broken lights of thee,

And thou, O Lord, art more than they.

Here’s a terrific reader-suggested benediction from The Avett Brothers.

To those of us prone to wander, to those who are broken, to those who flee and fight in fear – which is every last lost one of us – there is One who offers grace and hope. And may love have the last word. Now and forever.

Amen.

Thanks for reading.

Issue 137 (January 13, 2023)