Elizabeth Barton (1506-1534) was a wildly popular prophetess and nun known as “The Holy Maid of Kent” during the English Reformation.

As a teenager, she began claiming to have received divine revelations and predicting the future. Early on, her alleged prophetic utterances were mostly about heresy and healing. Some of them seemed to come true. English Catholic leaders like Thomas Wolsey and Sir Thomas More supported her, finding her popularity useful in their quest to resist the spread of Protestantism. She was a champion of the old religion when a new, more radical faith was insinuating itself within the educated and upper classes, threatening the traditional Catholic order in England.

In 1532, in response to Henry VIII’s movement away from Rome, Barton warned the king that if he divorced Catholic Queen Catherine and married Protestant Anne Boleyn, God would strike him dead within a year. She even prophesied where in Hell he’d spend eternity. Not surprisingly, the king wasn’t too pleased. And he did what he wanted anyway.

Henry married Anne – and it wasn’t Hal who ended up dead within a year (he lived 14 more). Instead, Elizabeth Barton was arrested and, in 1534, hanged. Her head was put on a spike at London Bridge, the only woman in English history who met such a fate.

That wasn’t in her forecast.

As Daniel Kahneman, the world’s leading authority on human error, has carefully explained, “The idea that the future is unpredictable is undermined every day by the ease with which the past is explained.” So, it remains unpredictable, but lots of folks are going to try anyway.

Every year at about this time, I outline the previous year’s load of terrible (mostly market) forecasts. Because bad predictions are the norm, the only part that’s hard is narrowing down the list of misses to use. Unless you made any of the predictions outlined herein, I trust you will enjoy this year’s edition of Forecasting Follies.

The above is from Jason’s brilliant book, The Devil’s Financial Dictionary.

Because there is so much nonsense to cover, this is a long TBL. Sorry. Not sorry.

If you like The Better Letter, please subscribe, share it, and forward it widely.

NOTE: Some email services will likely truncate TBL. If so, or if you’d prefer, you can read it all here. If it is clipped, you can also click on “View entire message” and you’ll be able to view the entire post in your email app.

Thanks for visiting.

Forecasting Follies

Despite our lack of talent at it, we humans are obsessed with prediction. (“Martians land on Earth. What does that mean for the market?”)

We all tend to suffer from what psychologists call hindsight bias, which makes us think we had predicted the future all along, that what happened was inevitable, and everybody should have seen it coming. But it’s a fraud.

As the mathematician Alfred Cowles observed decades ago, people “want to believe that somebody really knows.”

Nobody does.

That’s why, every year, the examples of poor forecasts and predictions are legion. The economy, the markets, and the world-at-large provide unlimited fodder for them.

As John Kenneth Galbraith succinctly (and correctly) stated, “There are two kinds of forecasters: those who don’t know, and those who don’t know they don’t know.” Stock market forecasts reestablish this truth year after year.

As Kahneman emphasized, “Claims for correct intuitions in an unpredictable situation are self-delusional at best, sometimes worse.” Much worse. And it happens anyway.

Every December, Wall Street denizens saddle-up and produce seemingly earnest, highly specific forecasts for where the S&P 500 will be at the end of the next calendar year. However, the price of something is discovered by what someone else is willing to pay for it and not by some intrinsic value or by some declaration of expectation. What someone else is willing to pay for it is based on what they believe – about the past, present, and future. Beyond the present lies imagination. And lots of surprises. That’s why the markets are much more of a mind game than a math game. And that’s why markets will always be exceedingly hard, even when the math seems easy or the future seems certain.

Beginning nearly a century ago, Cowles began looking at the market forecasts of the time and kept finding them wanting.

As outlined in his Expert Political Judgment, Wharton’s Philip Tetlock looked at 82,361 economic and political forecasts by 284 experts between 1987 and 2003. These experts made a living “analyzing” and pontificating on political and economic developments. He concluded that chimpanzees throwing darts at a board full of predictions would be more accurate than these alleged experts.

The CXO Advisory Group set out to determine whether alleged stock market “experts” provide useful insight. To find the answer, CXO collected and investigated 6,584 forecasts from 2005-2012 for the U.S. stock market offered publicly by 68 supposed gurus with a wide variety of styles and predilections. They found that their accuracy was worse than a coin-flip: just under 47 percent. A similar academic study from 2018 found roughly 48 percent accuracy. This 2023 academic study of survey forecasts got similar results.

On average, the median Wall Street forecast from 2000 through 2023 missed its target by an astonishing 13.8 percentage points annually. That’s more than double the actual average annual performance of the stock market over that period.

In December of 1994, Orange County, California, filed for bankruptcy protection after Robert Citron, its chief investment officer, lost billions of dollars speculating on fixed income derivatives. He bet big that interest rates would not rise, but they did anyway. When asked (a year earlier) why this wasn’t risky, Citron intoned, “I am one of the largest investors in America. I know these things.”

He didn’t.

Predicting market performance is much more a matter of luck than skill.

Truth be told, bad forecasting is utterly human and, perhaps more dangerously (as my friend Jason Zweig continues to demonstrate), we misremember our forecasts – thinking they were a lot better than they were.

Nobody can know what’s going to happen. It’s physics’ three-body problem applied to the global economy’s trillions of inputs. There are far too many variables for forecasting to be a viable endeavor. We ought to be highly skeptical (or worse) of any prediction made about complex systems.

As my friend Morgan Housel has explained, “Every forecast takes a number from today and multiplies it by a story about tomorrow.” We might have good current data, but “the story we multiply it by is driven by what you want to believe will happen” and what you’ve decided makes the most sense. Usually, the best story wins, correlation to reality not required.

Kahneman highlights the “illusion of understanding” – our predisposition to concoct stories from the information we have on hand. “The core of the illusion is that we believe we understand the past, which implies that the future should also be knowable.”

It isn’t.

Moreover, history is driven by surprising events while forecasting is driven by predictable ones. Let the great Peter Bernstein explain more precisely (Peter L. Bernstein, “Forecasting: Fables, Failures, and Futures – Continued,” in Economics and Portfolio Strategy, November 15, 2002, p. 5).

“The very idea that a forecaster can spin a bunch of outcomes whose probabilities add up to 100 percent is a kind of hubris. Risk means that more things can happen than will happen, which in turn means that the scenarios we spin will never add up to 100 percent of the future possibilities except as a matter of luck. Like it or not, the unimaginable outcomes are the ones that make the biggest spread between expected asset returns and the actual result.”

As Jason Zweig put it, “The only true certainty is surprise.” Or, as Morgan wrote in his new book, Same As Ever, there is a very good reason we suffer this weakness. “We are very good at predicting the future, except for the surprises – which tend to be all that matter.”

“No matter how much we may be capable of learning from the past,” Hannah Arendt wrote, “it will not enable us to know the future.”

In practical terms, per Kahneman, “The world is incomprehensible. It’s not the fault of the pundits. It’s the fault of the world. It’s just too complicated to predict. It’s too complicated, and luck plays an enormously important role.”

It was the Nobel Prize-winning physicist Niels Bohr, or Hall of Fame New York Yankees catcher Yogi Berra or, perhaps, neither one of them, who coined the phrase: “Predictions are hard to make, especially about the future.” Whoever it was, he or she was right.

But many are going to try anyway, which is what makes this endeavor so much fun each year. If you doubt the (obvious) conclusion that humans are truly dreadful at predicting the future, or merely want to have a laugh at human silliness, we have plenty of evidence to examine. And examine it we shall.

Pretty much everybody in Washington and on Wall Street got 2022 badly, absurdly wrong – from the Fed’s insistence that inflation would be transitory to the Wall Street analysts who projected a solid year of gains for stock and bond markets. Instead, the S&P 500 lost 18 percent, inflation climbed to a four-decade high, nearly tripling the Federal Reserve’s full-year forecast, and bonds had their worst year ever.

As 2023 dawned, these same “experts” were determined not to make the same mistake again. Or maybe they were fighting the last war. Either way, they overwhelmingly called for more doom and gloom, being remarkably astute at analyzing what had already happened.

SPOILER ALERT: The S&P 500 gained 26.06 percent in 2023.

Current trends are not permanent trends.

The average forecast of handicappers tracked by Bloomberg called for a decline1 in the S&P 500 in 2023, the first time the aggregate prediction was negative since at least 1999. Such negativity is highly unusual since the firms offering these outlooks are in the business of selling securities. Perhaps worse (in terms of prediction), the variance was immense, from down 17 percent to up 10 percent.

For example, Morgan Stanley’s Mike Wilson, picked by institutional investors as Wall Street’s best strategist, thought the bear market would continue, and the S&P 500 would fall hard before finishing 2023 at 3,900, pretty much where it began.2 At Bank of America, rate strategist Meghan Swiber was telling clients to prepare for a plunge in U.S. Treasury bond and note yields to forge a huge rally (she wasn’t alone). And, at Goldman Sachs (as at JPMorgan and elsewhere), strategist Kamakshya Trivedi was pitching Chinese assets because he thought the economy there would finally roar back from Covid lockdowns. Together, these three forecasts became, in essence, the consensus view.

They were wrong, wrong, and wrong.3

The buy-side, while less bombastic, wasn’t much better than the sell-side.

As usual, the indispensable Jason Zweig nailed it.

In December 2022, Marko Kolanovic, the JPMorgan Chase strategist who had insisted through much of that year that stocks were on the cusp of a rebound, capitulated and turned bearish, just in time for the rally.

Chris Senyek, chief investment strategist at Wolfe Research, called for the U.S. economy to crater (to -3 percent GDP), with inflation remaining stubbornly persistent, leading to “stagflation,” and a market collapse of 35 percent. He only missed it by 60 percentage points.

In May, with the S&P up nearly 10 percent on the year, Morgan Stanley’s Wilson – the public face of the bears – doubled down on his negativity, urging investors not to be duped: “This is what bear markets do: they’re designed to fool you, confuse you, make you do things you don’t want to do.” At least he got that right. Sort of. By year-end, he was ducking interviews.

Goldman Sachs called for double-digit gains in China while Morgan Stanley turned overweight on Chinese stocks in December 2022 and, as noted above, were far from alone, as most expected the world’s second-largest economy would get a lift as the government relaxed Covid-19 restrictions. But the reopening revival failed to materialize. Stocks are nowhere near pre-pandemic levels, and China’s property debt crisis swallowed even more companies. The MSCI All-World Index gained over 22 percent in 2023. The MSCI China Index lost 11.2 percent.

The once “Bond King,” Bill Gross, continued his efforts to return to relevance by hating the market. He might have more success were he right. Or close. But the current “Bond King” didn’t get it right, either.

Hedge fund exposure to technology stocks hovered near multiyear lows last January when the fantastic artificial intelligence trade took flight. They were shut out from just the sort of historically lucrative trade that they are paid to capture.

During the best week for stocks of the year, and a tremendous year it was, the Barron’s Big Money poll showed only 12 percent of those surveyed were bullish. Meanwhile, during that same week, Goldman Sachs data showed hedge funds were the least net long U.S. equities in 11 years.

Halfway through 2023, Liz Ann Sonders of Schwab called for a flat second half due to a “rolling recession.” The S&P 500 gained over 7.5 percent in the second half of the year. Her fixed income counterpart, Kathy Jones, saw 10-year U.S. Treasury note yields approaching 3 percent. UBS went even further, calling for U.S. 10-year yields to drop to as low as 2.65 percent by the end of the year. The 10-year U.S. Treasury note ended 2023 yielding 3.86 percent, just about where it began the year.

Bob Doll called for recession, a flat market, value to beat growth, and for active managers and international stocks to outperform. Oh-for-five.

Many strategists, economists, and other analysts also kept calling for a Fed pivot ...

... that hasn’t yet arrived.

When Sam Bankman-Fried was at Jane Street Capital (before he became famous for FTX and convicted of fraud), he built a system to get the 2016 U.S. Presidential election results before any media outlet could broadcast them. It worked, and the Jane Street team knew Donald Trump had shocked the world and defeated Hillary Clinton before anyone else. But they still managed to lose money – a ton of money ($300 million!) – on the trade because they bet against U.S. markets into a big post-election rally.

Even were we to get the forecast right, we’d likely make the wrong trade.

For example, if, say five years ago, you knew that there would be a global pandemic and that Pfizer would be the leading manufacturer of a vaccine to deal with the virus that would generate sales of over $70 billion in 2021-22, I’m guessing you’d eagerly bet that Pfizer would outperform the market.

We have trouble forecasting even 30 seconds into the future.

Michael Burry got rich by being right once in a row. He called the 2008-09 financial crisis but has kept calling for replays and kept being wrong.

As always, Jeremy Grantham, like Harry Dent, Gary Shilling, Greg Jensen, and John Hussman, predicted a crash (when they are – eventually, maybe even later today – right, I predict none of them will remind us of the dozens of times they were wrong). Not to be outdone, Stansbury Research said stocks would fall much further in 2023 and, like Japan, may not recover in our lifetimes. If that weren’t enough, Rod Dreher kept calling for imminent societal collapse. So did Ron Paul. What’s the number of predicted collapses before “imminent” has no meaning?

Last January, Wells Fargo analysts labeled the already sunken stock price of Silicon Valley Bank as the “deal of the century.” Barely six weeks later, the bank failed.

As he so often does, Warren Buffett got this right, too: “Forming macro opinions or listening to the macro or market predictions of others is a waste of time. Indeed, it is dangerous, because it may blur your vision of the facts that are truly important.”

In response to the failings of market strategists, economists (“economisseds”) said, “Hold my beer.”

Anna Wong is chief U.S. economist for Bloomberg Economics. In October of 2022, her model of the U.S. economy showed a 100 percent chance of a recession happening in 2023. Not 95. Not 98. Not even 99. 100 percent! No hedging. No margin for error. At least so far, the inevitable recession hasn’t arrived. The model was still reading 100 percent in June, when Bloomberg quietly stopped publishing the data.

Broadly speaking, in 2021, economists wrongly expected inflation to prove “transitory.” In 2022, they underestimated inflation’s staying power. They came into 2023 predicting that the Federal Reserve’s rate increases, meant to cure inflation, would plunge the economy into a recession.

All wrong.

In the 4th quarter of 2022, a survey of more than sixty economic forecasters from universities, businesses, and Wall Street provided a consensus view. The United States was “forecast to enter a recession in the coming 12 months as the Federal Reserve battles to bring down persistently high inflation, the economy contracts and employers cut jobs in response.” Moreover, the surveyed economists expected inflation-adjusted GDP “to contract at a 0.2 percent annual rate in the first quarter of 2023 and shrink 0.1 percent in the second quarter.” They also predicted that the unemployment rate, which was then 3.5 percent, would rise to 4.3 percent by June.

Nopity, nope, nope, nope.

Among other errors, economists badly underestimated inflation, underestimated consumer spending, and underestimated the strength of the labor market.

As they saw it, barely 12 months ago, recession was pretty much inevitable and the outlook for stocks wasn’t much better. They cited any number of red flags: war in Europe; the Fed was still raising interest rates; the yield curve was inverted; Americans were spending down their pandemic savings; the housing market was in decline; America’s leading economic indicators has fallen for nine months in a row; and banks were tightening their lending standards.

“We expect a downturn in global GDP growth in 2023, led by recessions in both the U.S. and the eurozone,” BNP Paribas wrote in the bank’s (representative) 2023 outlook, titled “Steering Into Recession.”

The economy and the market took those red flags and started a parade.

As Bloomberg reported, Barclays Capital said 2023 would go down as one of the worst for the world economy in four decades. Ned Davis Research put the odds of a severe global downturn at 65 percent. Fidelity International reckoned a hard landing was unavoidable.

It seemed like everybody thought so.

To be sure, recession expectations seemed historically aligned.4

Even the relatively few relatively optimistic analysts predicted the U.S. economy would grow much more slowly than it has over the past 20 years. They projected growth for 2023 would slow to about 0.5 percent, on average. Goldman Sachs had the rosiest outlook, projecting 1 percent growth in U.S. gross domestic product.

The Fed did keep raising interest rates – at the fastest clip since the 1980s, a regional banking crisis felled Silicon Valley Bank and others, and war broke out in the Middle East while continuing in Ukraine.

Still, the economy, like the market, kept marching. As of this writing, the most recent data show 4.9 percent GDP growth. Analysts of all stripes got the gloom and doom wrong, and missed on the boom entirely.

The Brookings Papers on Economic Activity claims to be America’s leading forum for relating academic research to “the most urgent economic challenges of the day.” The lead presentation at the September 2022 conference was a paper on inflation. Its conclusions were dismal. Harvard’s Jason Furman, one of the assigned discussants, called it “the scariest economics paper of 2022,” because it suggested that to get inflation down to 2 percent “we may need to tolerate unemployment of 6.5 percent for two years,” a view which garnered little dissent. However, the unemployment rate remained exceedingly low and is just 3.7 percent today.

In November 2022, The Economist published a piece entitled, “Why a global recession is inevitable in 2023.” It wasn’t.

Mohammed El-Erian is a respected economic sage, with a prestigious academic post at Cambridge University and a senior advisory position at the international financial firm Allianz. On October 5, he warned that the Federal Reserve’s commitment to keeping interest rates high to quell inflation would sap the U.S. economy and thus diminish the likelihood of a “soft landing.” The Fed’s policy, he wrote, “compounds the erosion in financial, human and institutional resilience.” Just two days later, the Labor Department announced that the U.S. economy had gained 336,000 jobs in September.

Bridgewater’s Ray Dalio predicted recession. David Rosenberg is still predicting one, as he has since early 2022. JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon worried that the erosion of consumers’ pandemic savings by price growth “may very well derail the economy and cause a mild or hard recession.”

I could go on-and-on … and maybe have already.

In October 2022, supposed “top economists” were “unanimous” in predicting interest rates would be “higher for longer” (today, it’s “lower and sooner”). Interest rates topped out the very next day.

Nobody has more and better data than the Federal Reserve. How accurate have the Fed’s projections been historically?

Not very. Academics and others confirm it (see here, here, here, here, and here). The Fed itself does, too.

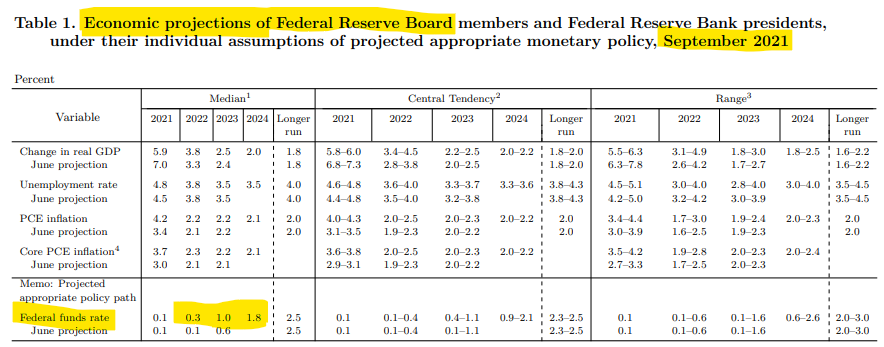

For example, note the following September 2021 forecasts when CPI was already above 5 percent. Back then, the Fed was forecasting rate hikes to only 1 percent by the end of 2023, with inflation coming right back down to 2 percent, inflation they called “transitory.”

Oops.

Instead, we got the highest inflation rate in the U.S. since the early 1980s (over 9 percent CPI) and a Fed Funds Rate above 5 percent. So, even when higher inflation was staring them right in the face, the Fed experts didn’t see it coming. Which is why you probably shouldn’t put much weight on their current forecasts (or anybody else’s, for that matter). They can’t predict the future any better than anyone else, even when it comes to their own policy rates, and despite their huge information advantage.

After going up more than he expected, Atlanta Fed President Raphael Bostic now says inflation has come down more than he expected.

As Fed Chair Jerome Powell candidly put it, “we are navigating by the stars under cloudy skies.”

At best.

We will never act with perfect foresight. We will rarely act with decent foresight. Living with uncertainty, after all, “remains the essence of the human condition.” We will always have to navigate challenging and changing conditions, relying on experience, training, instinct, and imperfect assumptions, prone to our old familiar flaws (chiefly, “our never-failing propensity to discount the future”).

This may not be an inspiring conclusion, but it is how the world works. Inexorably.

Totally Worth It

How is it that these guys aren’t stars?

Feel free to contact me via rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or on Twitter (@rpseawright) and let me know what you like, what you don’t like, what you’d like to see changed, and what you’d add. Praise, condemnation, and feedback are always welcome.

The market capitalization of the entire U.S. stock market in 1990 was about $2.8 trillion. That’s roughly what two companies, Apple and Microsoft, are each worth today.

Of course, the easiest way to share TBL is simply to forward it to a few dozen of your closest friends.

Out of the nearly 10,300 mutual funds and ETFs in the United States, the listed portfolio managers own no shares in the funds they manage in 5,900 of them.

You may hit some paywalls below; most can be overcome here.

This is the best thing I read in the last week. The funniest. The coolest. The most interesting. Also interesting. The most optimistic. The most absurd. The most insane (in a good way). The most insane (in a bad way). The most thought-provoking. Blasphemy. Stop with the math.`

Please send me your nominations for this space to rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or via Twitter (@rpseawright).

Many recognize “Auld Lang Syne” (paraphrased: “for old times’ sake”) as a Scots-language poem set to music and often sung just as the clock strikes midnight on the last day of the year (more here). Written in what some describe as “light Scots” by the Scottish poet Robert Burns, each verse becomes more Scottish as you continue to recite it. Burns’ poem ends with this:

And there’s a hand, my trusty fere! And gie’s a hand o’ thine! And we’ll tak a right gude-willie waught, For auld lang syne.

Roughly translated, this means, “take my hand and here is mine in return. Share a pint and remember the good, old times.” Happy New Year!

The TBL Spotify playlist, made up of the songs featured here, now includes over 270 songs and about 19 hours of great music. I urge you to listen in, sing along, and turn up the volume.

Bill Belichick, often described as a dastardly villain, parted company with the New England Patriots this week. I get the reputation, but that wasn’t my experience. We lived in the some town when he was defensive coordinator of the Giants and were part of the local Jaycees chapter together. He was unfailingly nice and hysterically funny. Oh, the stories he told, especially about Lawrence Taylor. Each year, he got nearly the entire Giants defense to show up to play a charity game with us at the local high school (my blocking Pepper Johnson’s shot and going end-to-end to score on him is one of my all-time sports highlights). I’m sure he doesn’t remember me, but I have great memories of him. Best wishes, Bill, for whatever comes next.

My ongoing thread/music and meaning project: #SongsThatMove

Benediction

We live on “a hurtling planet,” the poet Rod Jellema informed us, “swung from a thread of light and saved by nothing but grace.”

To those of us prone to wander, to those who are broken, to those who flee and fight in fear – which is every last lost one of us – there is a faith that offers grace and hope. And may love have the last word. Now and forever. Amen.

As always, thanks for reading.

Issue 162 (January 11, 2024)

There are other groupings of (bad, of course) forecasters that provide different overall averages, but the general trend remains the same.

Wilson finally conceded in July that he had been too pessimistic for too long, but still insisted that U.S. stocks would fall more than 10 percent before the year was out. They didn’t.

Kudos to Tom Lee, head of research at Fundstrat Global Advisors, and Leuthold’s Jim Paulsen, for pretty much getting it right. This time. Katam Hill’s Adam Gold elevated Nvidia to his highest-conviction pick just over a year ago in the grip of the stock’s biggest drawdown in 14 years. That was a very good call.

According to one survey, 59 percent of Americans think the U.S. is in a recession right now, which is another thing entirely.

A splendid and timely write up.

Bob, I’m sitting with my cuppa this morning trying to figure out WTF the Iowa caucus means. And by chance I stumbled upon an old quote of yours:

“We are surprisingly ignorant of why we do what we do. Our explanations are sometimes wholly fabricated, and almost certainly never complete. But that’s not how it feels. Instead, it feels like we know exactly why we do what we do. This is confabulation: A mostly self-delusion whereby we guess at plausible explanations for our choices and then regard those guesses as introspective certainties. Bottom Line: Much of what we think of as “self-knowledge” is ongoing self-interpretation. Our on-the-fly adjustments can be so quick and so facile that we don’t recognize a change as change.”

Bob Seawright

I sure hope that your words explain the ridiculousness of the Iowa cohort and bode well that our national thought process will change for the better.