Things Change

Things change more and faster than we think.

In July 1993, the Walt Disney Company issued $300 million 100-year “Sleeping Beauty bonds.” Those who were unenthused called them “Mickey Mouse bonds.” Or just plain goofy.

They bore a 7.55 percent coupon with a July 15, 2093 maturity, callable in 2023 at $103.02, declining to 100 percent of face value after July 15, 2043. It was the first century-bond, at least in the U.S., since 1954, and beat Coca-Cola’s issuance of 100-year, no-call bonds by a day. The Disney deal was announced as a $150 million issuance, but convexity and duration demand doubled the deal’s size. The debentures yielded nearly 100 basis points (one percent) more than the (off-the-run) 30-year U.S. Treasury bond.

Some pension and insurance companies, which have some very long-term liabilities to match, found the duration attractive. But many agreed with Pimco’s then “Bond King,” Bill Gross, who thought Disney was simply locking in “low yields” for a long time and didn’t find the paper attractive as a buyer.1

That idea wasn’t crazy. The bond market was barely a decade removed from a 20 percent fed funds rate, and the market’s leaders remembered it well. Still, it turned out to be wrong. Yields on the 30T rose just over a year later to about 8 percent but haven’t seen anything like those levels since.

Owners of the Disney bond today continue happily to clip a 7.55 percent coupon.

The Wall Street Journal‘s headline announcing the issuance: “Disney Amazes Investors With Sale of 100-Year Bonds.”

I was working institutionally at the time on the cavernous Merrill Lynch fixed income trading floor at the World Financial Center in New York City and was involved in the deal. We were Morgan Stanley’s co-manager. My favorite client, a pension manager for over 40 years, sardonically reminded me that someone buying 100-year bonds issued by the world’s leading entertainment business a century before would have purchased the debt of a player-piano company.

It’s easy to miss how much things change over time (see here). That’s the subject of this TBL.

If you like The Better Letter, please subscribe, share it, and forward it widely.

If you’re new here, check out these TBL “greatest hits” below.

NOTE: Some email services may truncate TBL. If so, or if you’d prefer, you can read it all here. If it is clipped, you can also click on “View entire message” and you’ll be able to view the entire post in your email app.

Thanks for reading.

Things Change

It’s easy to miss how much things change over time. It should be no surprise that Warren Buffett has a mechanism to “see” this more accurately. It’s his favorite critical thinking exercise. The first time they met, over the Fourth of July weekend in 1991, Buffett introduced it to Bill Gates.

“On that first day, [Buffett] introduced me to an intriguing analytic exercise that he does,” Gates said. “He’ll choose a year — say, 1970 — and examine the 10 highest market-capitalization companies from around then. Then he’ll go forward to 1990 and look at how those companies fared. His enthusiasm for the exercise was contagious.”

The exercise is productive because, to paraphrase Theodor Reik, history doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.

The idea is simple, as Gates noted. Choose a year and consider the top 10 companies by market capitalization. Then look forward to see how the list changes over time to spot emerging trends and to consider what has changed and what hasn’t, and how this information may impact your investment thesis. You can watch how those changes occur, from 1980-2020, below.

I started driving in 1972. Gasoline was $0.36 per gallon. Really. The oil crisis instigated by OPEC arrived quickly, with roaring inflation, rising prices, poor stock market returns, and long gas lines. By 1980, the price of a gallon of gas had shot up to $1.19, a more than three-fold increase.

That year, the S&P 500 was dominated by oil companies. Given the extent of the price increases, that shouldn’t be surprising.

The S&P top ten list included six of them: Exxon, Standard Oil of Indiana, Shell, Standard Oil of California, Mobil, and Atlantic Richfield. It also included Schlumberger, a oil services company. That’s seven out of ten oil-related. But 1980 was an oil price peak: $35 per barrel. That’s equivalent to $129 per barrel in 2024 dollars. By way of comparison, oil closed 2024 at $74.69 per barrel, down 3.6 percent from $77.50 at the start of the year. By 1990, only Exxon and Shell remained in the top ten.

Along with Exxon and Shell, IBM, GE, and AT&T remained in the top ten in 1990. IBM retained the top spot, while GE jumped from tenth to third. A much smaller AT&T also remained, having fallen from second to ninth after the 1984 spin-off of seven regional local carriers (the “Baby Bells) due to the settlement of the federal government’s antitrust enforcement action. Newcomers included consumer companies like Coca-Cola and Philip Morris, pharmaceuticals like Bristol-Myers Squibb (Bristol-Myers and Squibb had merged in 1989) and Merck, and Walmart, which was driving U.S. retail.

Four of 1990’s top ten were still there in 2000. GE jumped over Exxon to the top spot as the oil company (which had bought Mobil in 1998 in what was then the biggest merger ever) stayed at number two. Walmart moved from eighth to sixth, while AT&T dropped from seventh to ninth.

GE was a diversified behemoth, labeled an industrial but largely a de facto financial. The dot-com bubble was deflating. Gates’ Microsoft, Cisco, and Intel were there, but at roughly half their earlier market cap peaks. The 1999 list included those three plus Lucent, IBM and AOL. Walmart was on top of the retail world, driving mom-and-pop shops out of business nationwide. Pharmaceuticals remained strong as Pfizer entered the list at third and Merck stayed in the top ten (it dropped from sixth to eighth, but grew its index share from 1.6 to 1.8 percent). Two big financials hit the list for the first time: Citi and AIG.

IBM topped the list in 1980 and 1990, but was off it entirely by 2000. The computer mainframe giant began encountering difficulties in the late 1980s, marked by substantial losses , which surpassed $8 billion in 1993. The mainframe-centric corporation lost touch with its customers, squandered its technological leadership, and missed out on the personal computer revolution.

Also off the list for 2000: Philip Morris (still profitable due to international markets, but tobacco was more and more a social pariah in the U.S.), Shell (Exxon was the only oil company remaining in the top ten, but had merged with Chevron the year before), Bristol-Myers Squibb, AT&T (facing competition from the likes of MCI and Sprint — it seemed like telemarketers hawking long-distance service, who had become a thing, called my landline a dozen times a night then), and Coca-Cola (after peaking at number two in 1996, it began losing market share to bottled water, juices, and other non-carbonated drinks).

Exxon and GE were the only companies from the 1980 list still on it in 2000.

The ten-year period between 2000 and 2009 is often called a “lost decade” for U.S. stocks, which faced major drawdowns around the turn of the century (the “tech wreck”) and the Great Financial Crisis of 2008-09. From January 2000 through December 2009, the S&P 500 lost 0.72 percent per annum, including dividends.

In 2010, Exxon stayed at number one (oil prices had skyrocketed over the previous ten years), Microsoft moved up to third, GE fell to fifth, and Walmart stayed sixth, but only Exxon grew its market cap significantly (Microsoft’s was basically flat; GE’s and Walmart’s fell). Chevron, which had been known as Standard Oil of California, returned to the top ten at number eight. IBM, at nine, made it back, too. The altogether new names were Apple, Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway, Google (now Alphabet), and Proctor & Gamble. Pfizer, Cisco, Citi, AIG, Merck, and Intel fell out of the top ten. Citi and AIG almost blew up entirely during the Great Financial Crisis.

In 2008, Citigroup’s stock price dropped almost 80 percent. AIG fell over 90 percent. Both were bailed out by the U.S. government.

Exxon’s growth and Chevron’s return were largely predicated upon America’s “energy revolution” and (mostly) the big increase of world oil prices. Indeed, energy was the best performing market sector from 2000-2015. From the tech sector, the top ten included four names, including the entry of Apple (the first-generation iPhone was announced by then–Apple CEO Steve Jobs on January 9, 2007) and Google (which had only come to market in 2004). IBM’s return was fueled by growing earnings, growing dividends, and buying back stock at cheap valuations. Even Buffett, whose BKB made the list, was about to buy (he bought into IBM in 2011, although the trade didn’t turn out well; he was out in 2017, having earned about 5 percent per year, including dividends).

All 1990 list members are gone by 2010.

The 2020 top ten list is very tech heavy. Apple, buoyed by quality products, Buffett’s big position (he bought his first stake in 2016 and added very substantially in 2020), and very sticky customers, led the parade. Microsoft, Amazon, Facebook (now Meta), Tesla, and Alphabet (A and C) hold down spots 2-7. Berkshire Hathaway, Johnson & Johnson, and JPMorgan Chase round out the list. Amazon, Facebook, Tesla, J&J, and Chase are new to the list; (Google parent) Alphabet added a second class of stock to the list; Exxon, GE, WMT, Chevron, IBM, and P&G fell out.

Only Microsoft remained from the 2000 list.

As 2025 dawned, Apple, Microsoft, Meta, Tesla, Alphabet A and C, and Berkshire Hathaway remained top ten stocks. Nvidia was the new, big giant. Broadcom was now on the list, too. JPM dropped to 11. Exxon came in at 14. Walmart, P&G, and J&J were in the top 25. We’ll see what 2030 and beyond bring.

What can we learn from this exercise or, at least, be reminded of? Here are ten to start.

It’s hard to stay on top.

The broader economy matters. Often a lot.

The S&P 500 experiences a surprising amount of turnover. Half of the top ten list seems to change every decade. More broadly, since 1980, roughly one-third of the S&P 500 constituents have turned over during the average 10-year period. The speed of such changes is increasing. The 30 to 35-year average tenure of S&P 500 companies in the late 1970s is likely to shrink to 15-20 years this decade.

America is no longer the manufacturing power it used to be. When I learned to drive, industrial companies made up about one-third of the S&P 500. Such companies make-up about one-seventh of the index today (although, after decades of decline, there has been an uptick lately).

Technology growth has exploded. When I learned to drive, there were only 16 Information Technology companies represented in the S&P 500, the second-fewest of any industry represented. There are about four times that number now.

You won’t see it from the top ten lists, but nobody should be surprised at the drastic changes we’ve seen in traditional retailing. Dropping out of the S&P 500 during the pandemic were an array of venerable retailers, such as Nordstrom, Macy’s, Kohl’s, and Tiffany & Co. Amazon has ascended.

Politics and the law have big impacts (see, e.g., AT&T).

Changing social mores matter (see, e.g., Philip Morris).

Changing tastes matter (see, e.g., Coca-Cola). Thus, adaptability is crucial.

Artificial intelligence (e.g., Nvidia), and clean technology (e.g., Tesla) remain industries to watch.

What do you have to add?

Totally Worth It

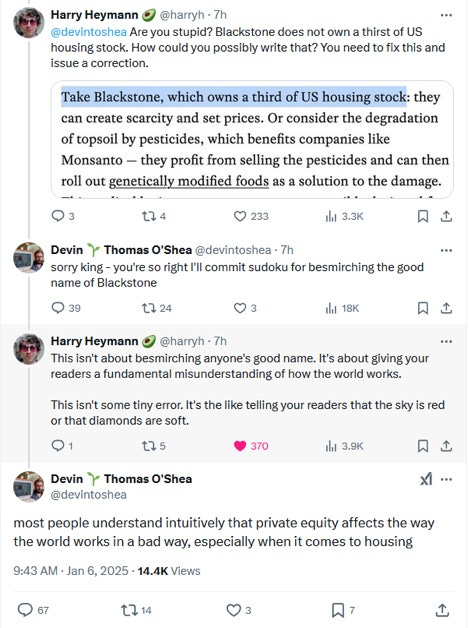

Jacobin published a piece last week that (absurdly) claimed Blackstone owns one-third of U.S. housing stock. After being dunked on mercilessly for a few hours on social media, the unabashedly socialist magazine removed the offending statistic and (sort of) issued a correction.

“An earlier version of this article overstated the amount of U.S. housing stock that Blackstone owns.”

They did, but it doesn’t appear the author (at least) meant it.

It wasn’t a minor error, either. The correct number, conspicuously omitted by Jacobin in the correction, is something less than 0.05 percent. Since the current value of all U.S. housing stock is roughly $50 trillion (with a “t”), if Jacobin were correct, Blackstone would own housing assets worth about $17 trillion. To get a sense of the magnitude of the error, that’s akin to saying the federal budget totals about $5,000 trillion, a gallon of milk costs over $3,000, or that the Silk, with nearly 800 #1 hits, is the most successful band of all-time (if you want to know, the Beatles have the most number ones ever: 20, which is quite a ways from nearly 800).

Feel free to contact me via rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or on Twitter (@rpseawright) and let me know what you like, what you don’t like, what you’d like to see changed, and what you’d add. Praise, condemnation, and feedback are always welcome.

Of course, the easiest way to share TBL is simply to forward it to a few dozen of your closest friends.

You may hit some paywalls below; some can be overcome here.

This is the best thing I’ve read recently. The scariest. The sickest. The saddest. The funniest (unless it’s this). The most thoughtful. The most insightful. The best shade. Moo Deng. The “everything” chart. RIP, Peter Yarrow, of Peter, Paul & Mary. In the video below, be sure to notice the audience singing along to this classic Bob Dylan song.

Please send me your nominations for this space to rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or via Twitter (@rpseawright).

On August 13, 1966, radio station KLUE in Longview, Texas, scheduled the nation's first “Beatles Bonfire.” Teens were urged to bring their Beatles records, posters, and the like, to the station, where they were piled high and set on fire. The very next day, the radio station was struck by lightning.

Benediction

Something spectacular happened when a terrific Brazilian metal singer takes on the traditional Christmas carol, “Angels We Have Heard on High.” It’s this TBL’s benediction.

We live on “a hurtling planet,” the poet Rod Jellema informed us, “swung from a thread of light and saved by nothing but grace.” To those of us prone to wander, to those who are broken, to those who flee and fight in fear – which is every last lost one of us – there is a faith that offers grace and hope. And may love have the last word. Now and forever. Amen.

As always, thanks for reading.

Issue 181 (January 10, 2025)

Why in the world didn’t the U.S. government issue lots of 100-year, 50-year, and 30-year paper when rates approached one-percent? It issued mostly short-term paper instead.