The Better Letter: How Lucky Are You?

A special basketball randomness edition in honor of March Madness

I feel lucky. I am lucky. Privileged even.

I live in a country with the expertise and wherewithal to create at least three highly effective vaccines to fight the current pandemic within an astonishingly short time and the capacity to get those vaccines into arms by the millions every day. I was able to take the time and make the effort to “chase” a first dose without jumping the line. When second appointments were being canceled left and right due to supply issues I was able to find and drive to an appointment off the beaten path and get my second dose.

It’s amazing.

That I am beyond lucky is also true in a much broader sense. Existentially even.

I have been disproportionately successful in winning NCAA Tournament pools over the years, too. Although I love basketball and watch more than my fair share, the biggest reason I have won those prediction contests is that I bet on my school and my school has been disproportionately successful in March Madness.

In other words, I’ve been lucky there, too. It’s almost like luck is contageous. Or that it compounds. Nick Heil explained it pretty well: “you never really know how lucky you are until your luck runs out.” It is the primary subject of this week’s TBL.

If you like The Better Letter, please subscribe, share it, and forward it widely. It’s free, there are no ads, and I never sell or give away email addresses.

Thanks for reading.

How Lucky Are You?

Hall of Fame pitcher Lefty Gomez often said, “I’d rather be lucky than good,” and that’s a sensible view. In a group of any size, who wouldn’t want to be the lucky one?

The NCAA Tournament field will be selected on Sunday. I will pay less attention than usual because we already know my alma mater’s string of 24 consecutive appearances is over.

However, I will still watch. I will create a bracket and try to predict who wins. I’ll do it with my family but you can play commercial challenges for prizes or just bragging rights. Play the NCAA version here and the ESPN version here (other options here). Succeeding is a lot harder than it seems like it ought to be.

There has never been a verifiably perfect March Madness bracket. That shouldn’t be surprising in that, assuming the odds of picking each game correctly are an even 50:50, the number of possible bracket outcomes is 9,223,372,036,854,775,808. That’s 9.2 quintillion. By way of comparison, there are something like 7.5 quintillion grains of sand on the earth. You’d have a better chance of making four holes-in-one in a single round of golf than of creating a perfect bracket.

That commonly cited one in 9.2 quintillion calculation assumes every game is a 50:50 proposition, which of course it isn’t. For example, a number 16 seed has only beaten a number one once (Wahoo-Wa). Still, the best gambler in my lifetime only picked winners about 57 percent of the time overall. So, if we assume a basketball expert is likely to predict tournament winners with 60 percent accuracy, this works out to the expert having just about a one-in-94 trillion shot of creating a perfect bracket. Better, but hardly great.

According to Duke math professor Jonathan Mattingly, even the average college basketball fan has a far better chance of achieving bracket perfection than that. Many March Madness matchups are relatively predictable when compared to pro games. According to Mattingly, adjusting probabilities based on seeding, the odds of picking all 65 games correctly is actually more like one in 2.4 trillion.

Using a different formula, DePaul mathematician Jay Bergen calculated the odds at one in 128 billion. The analysts at FiveThirtyEight say that for somebody who knows basketball, the odds might be as “good” as one in 2 billion. But those odds are still worse than your odds of winning the lottery.

Whichever calculation you prefer, if you are really lucky, your perfect bracket will last about halfway through Thursday’s opening slate of games. In other words, your odds of getting a perfect bracket are staggeringly small.

However, in 2009, a New Jersey grandmother set a craps world record over four hours and 18 minutes by rolling a pair of dice 154 times before crapping out. Her odds of doing that were one in 5.6 billion. So, there’s hope.

But not much.

The NCAA tracks all publicly verifiable March Madness brackets. According to that data, the longest verifiable streak stands at 49 games, set in 2019 by neuropsychologist Gregg Nigl, from Columbus, Ohio. He upended the previous mark of 39 correct picks, which was set in 2017. Nigl’s bracket finally went bust on game 50 (the third game on the second weekend – about a one-in-five-million shot). When asked the secret of his success, Nigl admitted to watching a lot of Big 10 basketball while also correctly conceding that getting that far came down to “a lot of luck too.”

The highly unlikely happens surprisingly often. “We tend,” wrote Nassim Taleb, “to underestimate the role of luck in life in general (and) overestimate it in games of chance.”

Despite remarkably long odds, Richard Lustig has won the lottery seven different times, Roy Sullivan survived being struck by lightning seven times, and the roulette wheel at the Rio in Las Vegas landed on 19 seven consecutive times. College GameDay basketball broadcasts offer one lucky student the opportunity to win a lot of money by making a half-court shot. The bottom of the net has been found on such 47-foot heaves four times in four visits to the University of Virginia. Doing it just once is about a one-in-50 proposition.

For the driver in this incredible video, what follows is truly a “black swan” event.

However, such highly unlikely events are much rarer than we commonly assume. As Han Solo says, “Never tell me the odds.”

In the NFL, more than 50 percent of game outcomes are random chance, and they seem to be getting more random. Moreover, that percentage is significantly higher in the playoffs leading to and including the Super Bowl, as teams are more evenly matched. That’s why even the best computer models accurately pick winners only about 70-75 percent of the time, with a ceiling of 76 percent, and why, on average, the better team only wins roughly three times out of four.

Let’s agree that forecasting the future is always difficult and that predicting how humans will perform under stress is insanely difficult. By most models, even the very best team in the tournament has only something like a 15-20 percent chance of winning it all. That’s why your office pool can be won by Janice in Accounting who has never seen a game and picks her winners based upon team colors and mascots.

As Churchill said, “All this shows how much luck there is in human affairs, and how little we should worry about anything except doing our best.”

Each of us should agree that predicting what will happen in the world, as in the markets, has many more variables and requires much more complex thinking than predicting the binary outcomes of basketball games. On the other hand, as the great playwright, Tom Stoppard, understood: “[T]here is really, really good news if you end up feeling lucky rather than clever.”

Henri Poincaré proved back in 1887 that the motion of three objects within the same system is non-repeating and thus chaotic. In other words, the historical pattern has no predictive power whatsoever with respect to where the objects will be in the future. There is no possible algorithm to solve this problem and no predictable pattern. Accordingly, nobody can solve the three-body problem and predict the future of such a system. That we cannot expect to predict the movements of just three independent variables more than suggests nobody should expect to be able to forecast the future.

As Stoppard postulated in his play, The Hard Problem: “In theory, the market [like life] is a stream of rational acts by self-interested people; so risk ought to be computable. But every now and then, the market’s behavior becomes irrational, as though it’s gone mad, or fallen in love. It doesn’t compute. It’s only computers compute.”

It doesn’t compute, of course, because markets are driven by people, who may be self-interested, but who aren’t necessarily rationally self-interested. They are mere human people, not computer people. They are yearning, hurting, illogical, infuriating — driven by the attraction Newton left out and by the devout hope that the better angels of our nature that Lincoln saw are real.

We want binary questions and answers in a world far messier and more complicated than that. So get your bracket done and in one time. Just don’t expect to win. And forget about the idea that it might be perfect.

Busted Bracket

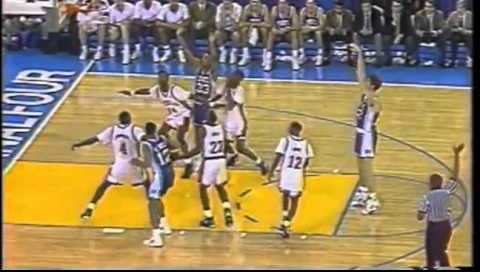

As shown above, the highly unlikely happens surprisingly often. In 1991, UNLV was the defending champion and came into the Final Four unbeaten and unchallenged. In the national semi-final, the Runnin’ Rebels met my Duke Blue Devils, a team UNLV had destroyed the previous year, 103-73, in the most lopsided championship game in NCAA Tournament history. It wasn’t as close as the final score might suggest.

Really.

It was U-G-L-Y in 1990 and nearly everyone expected more of the same in 1991. Happily, that wasn’t what happened. The highly unlikely happens surprisingly often.

This story relates to that game but isn’t about the game itself or even the tournament, exactly. In those days, Wall Street trading houses had big tournament pools that featured high entry fees with serious bragging rights and big prizes at stake. Significantly, because there were lots of traders involved, lots of trading went on. You could call almost any major shop and get two-sided markets on pretty much any aspect of the tournament including, of course, which team would win it all.

That final fact is noteworthy because one particular trader was sure that UNLV was going to repeat as champions. More particularly, he was absolutely convinced that Duke would not win the tournament and shorted the Blue Devils big without hedging — expecting to profit handsomely when elimination ultimately came. In other words, he was looking to make big money on the trade and not just on the spread.* My guess is that he was a prop trader wannabe. Significantly, losing would mean not just lost potential profits — he would have to ante up real cash. Worse, he would lose face on the trading floor.

As the expression goes, he was picking up pennies in front of a steamroller.

Our poor schlub was pretty nervous on the Monday after the UNLV upset, but Duke still had to beat Kansas that evening (ironically, it was April Fool’s Day) to win the title for the trader to have to cover his shorts. He feigned confidence, of course, but nobody was fooled. When Duke prevailed over the Jayhawks, 72-65, the fool was six figures (plus) in-the-hole.

The trader made good — sheepishly and painfully — but the brass learned a lesson. Thereafter, the big investment banks no longer allowed employees to organize tournament pools and trading on the pools that existed was strictly prohibited. It was even enforced. Rumor had it that this was part of a quiet agreement between regulators and internal compliance officials, who were understandably concerned about what had gone on. Wall Street pools still existed after that, of course, but they were run exclusively on the buy-side. We on the sell-side still played, but it wasn’t the same. There wasn’t any trading that I’m aware of. And that’s a good thing.

Traders are going to trade – on Apple, GameStop, or Duke – and gamblers are going to gamble. Upwards of $10 billion will be wagered on the NCAA basketball tournament this year, with “only” about $300 million bet legally. Without careful oversight, accountability, position limits, and careful hedging, it’s inevitable that people will get themselves in big trouble. That lesson applies to NCAA Tournament pools, to any security you might want to name, and to life.

_______________

* Interesting side note: One of the better mortgage traders I knew got his start betting sports in the dark ages before national lines and the internet. He’d bet the underdog in the favorite’s city and vice versa, taking advantage of wide disparities in the lines and creating what was effectively a wide bid/ask spread. He won both sides surprisingly often.

Totally Worth It

This is the ickiest thing I saw this week. The best. The sleaziest. The funniest, unless it was this. The sweetest, unless it was this. The coolest. The stupidest, unless it’s this. The evilest. The winningest. The most remarkable.

Two of my grandsons have a marble channel on YouTube. Please make their day and visit.

I’ve been writing The Better Letter for a year now. If there is a story, issue, or subject you’d like me to write about, please contact me via rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or on Twitter (@rpseawright).

In honor of TBL’s anniversary, here are four good issues you might have missed.

You may also contact me (again, via rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or on Twitter – @rpseawright) with questions, comments, and critiques. Don’t forget to subscribe and share.

Benediction

John Rutter’s The Lord Bless You and Keep You is a true benediction based upon the priestly blessing (Birkat Kohahim in Hebrew) found in the book of Numbers.

May it be so for each of you.

Thanks for reading.

Issue 54 (March 12, 2021)