On the first anniversary of the 9.11 attacks, Mary Chapin Carpenter listened to interviews of rescue workers describing how they sensed the presence of spirits at the Twin Towers site and felt an obligation to carry them out of that place “on their backs.” One told of going to Grand Central Station in order to send them home. Those stories led to this wonderful, haunting song in memoriam.

Nineteen years ago today, on another day that lives in infamy, at a little before 6:00 a.m., local time, I was sitting in front of my Bloomberg terminal in the downtown San Diego Merrill Lynch office when the first, cryptic hints of trouble at the World Trade Center crawled across the bottom of my screens.

The unmentionable odor of death would offend that September morning. Blind skyscrapers using their full height to proclaim their power collapsed below the surface of the earth, propelling an acrid cloud of blood and bone that billowed across Manhattan in war and remembrance.

I had been scheduled to fly to New York for work on September 10, 2001, and had reservations for the week at the Marriott World Trade Center, which would be destroyed when the Twin Towers collapsed. Instead, I stayed home to go to “Back to School Night” at my kids’ school.

I am really glad I didn’t get on the plane.

This little story about what happened to me on September 11, 2001 is, of course, insignificant within the context of the tragic losses, terrible evil, and timeless heroism of the “American epic” to which that day bore inexorable witness.

It is still my story. It provides context and a framing device to help me remember what happened and ponder what it means. It is emotional still.

We all have these sorts of stories – and they are the focus of this week’s TBL.

If you like The Better Letter, please subscribe, share it, and forward it freely.

Thanks for visiting.

Facts, Horrid and Stubborn

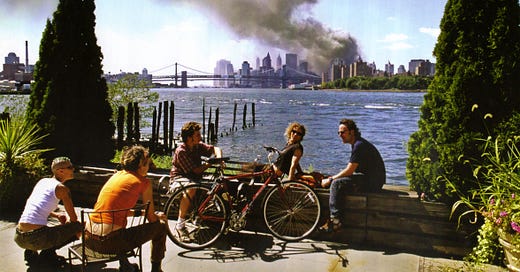

This photograph, taken at the Brooklyn waterfront during the afternoon of September 11, 2001, by German photographer Thomas Hoepker, is now one of the iconic images of that dreadful, terrible day. In Hoepker’s words, he saw “an almost idyllic scene near a restaurant – flowers, cypress trees, a group of young people sitting in the bright sunshine of this splendid late summer day while the dark, thick plume of smoke was rising in the background.” By his reckoning, even though he had paused for but a moment and didn’t speak to anyone shown in the picture, Hoepker was concerned that the people in the photo “were not stirred” – they “didn’t seem to care.”

Hoepker later began spinning a more expansive tale, comparing his photo to Breugel’s “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus,” a Renaissance painting in which a peasant continues plowing, seemingly unaware or unconcerned by the body of a boy plummeting from the sky into the sea, presaging the iconic “Falling Man” 9.11 image.

That September, Frank Rich wrote a 9.11 fifth anniversary column for The New York Times, framed by the “shocking” Hoepker photograph. Rich claimed that the five New Yorkers shown were “relaxing” and were already “mov[ing] on” from the attacks. Rich described them as being on “what seems to be a lunch or bike-riding break, enjoying the radiant late-summer sun and chatting away as cascades of smoke engulf Lower Manhattan in the background.” The Rich narrative then draws a remarkable conclusion.

“Mr. Hoepker’s photo is prescient as well as important – a snapshot of history soon to come. What he caught was this: Traumatic as the attack on America was, 9/11 would recede quickly for many. This is a country that likes to move on, and fast. The young people in Hoepker’s photo aren’t necessarily callous. They’re just American.”

For Rich, America’s desire quickly to move on from the 9.11 tragedy, foreshadowed by Hoepker’s image, meant we didn’t learn any lasting lessons from it. It was an easy and plausible – if utterly speculative – interpretation based upon the image alone, but wasn’t supported by any substantive evidence. However, and more importantly, as interpreted, it framed Rich’s desired narrative perfectly.

Even though a picture may well be worth a thousand words (1,506 in Rich’s case), those words needn’t be accurate.

The line between expectation and observation can be a very fine one. As the theologian Robert McAfee Brown said, where you stand determines what you see. And, as Oxford’s Teppo Felin pointed out, what we are looking for determines what is obvious.

Daniel Plotz quickly came forward with an alternative interpretation of the photograph. In his view, the five people in the picture had not ignored or moved beyond 9.11 but had “turned toward each other for solace and for debate.” To his credit, Plotz emphasized that he didn’t “really know” what the pictured people were doing or feeling and called upon them to contact him so as to set the record straight. Two did, and they repudiated Rich’s narrative in the strongest of terms.

The first to respond was Walter Sipser, a Brooklyn artist and the man on the far right in the image. “A snapshot can make mourners attending a funeral look like they’re having a party,” he wrote. “Had Hoepker walked fifty feet over to introduce himself he would have discovered a bunch of New Yorkers in the middle of an animated discussion about what had just happened.” Chris Schiavo, a professional photographer, second from the right in the photograph, also responded. She criticized both Rich and Hoepker for their “cynical expression of an assumed reality.”

Rich turned Sipser and Schiavo into “national symbol[s] of moral disgrace” via false pretenses. Hoepker and Rich, as we are all prone to do, interpreted the picture for their own purposes with a false certainty that neither the evidence nor common decency supported, much less required. Their desired narratives simply carried the day, facts notwithstanding. A decade after 9.11, long after he should have been aware of his mistake, Rich was still pumping the same false narrative: “Now, ten years later, it’s remarkable how much our city, like the country, has moved on.”

We love stories, true or not, almost from the cradle. Stories are crucial to how we make sense of reality. They help us to explain, understand, and interpret the world around us. They also give us a frame of reference to remember the concepts we take them to represent. Whether measured by my grandchildren begging for one (or “just one more”), television commercials, the book industry, data visualization, series television, journalism (which reports “stories”), the movies, the parables of Jesus, video games, cable news opinion shows, or even country music, story is perhaps the overarching human experience. It is how we think and respond.

Narratives need heroes, villains, character arcs, redemption, vindication, and meaning, all of which can overshadow or obscure what is unequivocally real, like facts and data.

Whether we like it or not, stories are powerful. An oft-cited Ohio State study found that a message in story form is up to 22 times more memorable than disconnected facts alone. The Significant Objects Project allowed researchers to sell worthless baubles on eBay for surprising amounts when they linked each one with a compelling story.

We are hardwired to respond to story such that a good story doesn’t feel like a story – it feels exactly like real life, but is most decidedly not real life. It is heightened, simplified, and edited. We prefer rhetorical grace and an emotional charge to precise linearity and the work of hard thought. Because we are inveterate simplifiers, we prefer a clean and clear narrative to a complex reality.

Reality is messy. Stories? Not so much. Stories can never be truly ordinary or they wouldn’t resonate and we wouldn’t stick around. Our lives are ordinary and we want to experience the extraordinary, to imagine being extraordinary. If the characters in a story are too real, it wouldn’t be a very good story. Much like Daniel Defoe’s famous description of the novel as “lying like truth,” Robert McCrum says, “The moral drive of fiction is faithfully to ‘get it right’ through the contrivance of making it up.”

Stories are the culture’s way of teaching us what is important. They are what allow us to imagine what might happen next – and beyond – so as to aspire to it or prepare for it. Indeed, we are always anxious to know what is going to happen next.

Because it feels so true, it isn’t hyperbole to say you’ve been lost in a story. A story turns us into willing students, eager to learn its message. It is how we sift through the raw data of our lives to ascertain what matters. Our brains are designed to analyze the environment, pick out the important parts, and use those bits to extrapolate linearly and simplistically about and into the future. The common reminder to public speakers that audiences won’t remember what they say but will remember how they were made to feel offers an important truth. We may learn facts and data but we feel stories, and that makes all the difference, allowing stories to be the best means available for communicating ideas.

Great stories offer an illusion of accuracy and completeness, justified or not. Whether it’s with pro wrestling and politics or, less obnoxiously, in “based on a true story” movies or the arts generally, occasional inaccuracy (clarification, augmentation, creative license, etc.) isn’t quite denied. It is an essential part of the spectacle. Distinctions and differences from linear fact, as a whole, are a feature of good storytelling, not a bug.

Where literalists see red flags, artists see a parade.

Still, there is a huge difference between, on the one hand, story, spin, or packaging and, on the other, falsehood, deception, or obfuscation.

Our thinking is governed by and about beliefs, reasoning, motivations, expectations, planning, and pain. Our brains are jazz musicians of a sort, improvising what it thinks are the best thoughts and behaviors in and for the moment. We are incessant but inconsistent creators. We are not detached reporters of either the outer or our inner worlds. Our brain acts far more as story-spinner than as objective reporter – more tabloid than academic research paper. However, we are such good story-spinners that we convince others – and ourselves too – that we’re reporting fact rather than creating fiction on the fly, making it up as we go along.

We think of our brains as linear processors of information. They aren’t. We are always wondering how the information we’re receiving fits together. Our stories provide coherence and overarching meaning, the basis for creating the desired connections. Accuracy is only an occasional by-product.

The keys to acquiring knowledge are collecting facts, drawing connections, making inferences, and predicting outcomes – the scientific method, broadly construed. However, our brains insist on finding links and patterns whether they truly exist or not. We’re biologically inclined to reduce complex events to a simpler, more palatable, more easily understood pattern – in other words, a story.

The risks of turning everything into a story and the deceptions of a good story have consequences. As Nassim Taleb explained, the narrative fallacy addresses our limited ability to look at sequences of facts without weaving an (often erroneous) explanation into them or, equivalently, forcing a logical link, an arrow of relationship upon them. Explanations bind facts together. They make them all the more easily remembered. They help them make more sense. Where this propensity often goes wrong is when it increases our impression of understanding. Or when we have the facts wrong.

Which brings me back to Frank Rich.

Five years after the towers came down, Frank Rich had a story to tell (and sell). It was a story of a “divided and dispirited” America that had lost touch with the horror of 9.11, of a forgetful nation desperate to move on, a divided nation insufficiently stirred. It was also and crucially the story of a callow, fear-mongering President with a selfish and secret partisan agenda far removed from committed sacrifice for the common good. It was a story of a once-great country that had moved on but not ahead. And he found the perfect picture to illustrate that story.

As a journalist, Rich had an obligation to check the facts supporting his story. By all appearances, he did not. Whether he tried to or not, the alleged facts upon which his story was predicated were blatantly and dreadfully wrong. That was an egregious error, an error that would make him look silly when the truth came out, as it so often does.

Many of our foibles (narrative and otherwise) are the result of our laziness. Sometimes the laziness is overt. Other times it is simply a function of the various shortcuts we take, perhaps understandably, to make life more manageable. Sometimes our stories are “too good to check.” Sometimes the point of the story matters so much to the author that its facts do not. Whatever the reason(s), Rich perverted the truth of what the Hoepker photograph actually portrayed. His purported facts, necessary for his proffered conclusion, were wrong, plain and simple.

Based on Jane Austen’s epistolary novel, Lady Susan, eventually published more than 50 years after her death, Love and Friendship is a terrific film. This witty black comedy of machinations and manners feels like it has more in common with Oscar Wilde than the author of Sense and Sensibility. “Facts are horrid things,” Lady Susan (Kate Beckinsale) shrugs in one scene (directly following the book), rejecting culpability for having slept with someone else’s husband. Hearing Lady Susan spinning her having been unmasked as a duplicitous scoundrel as everyone’s shame but her own is a masterful and, in context, hysterical tour de force. At least she didn’t read other people’s correspondence. Mere “horrid” facts will not deter her.

By comparison, consider the American patriot who would become our second president. When making his legal defense of British soldiers during the Boston Massacre trials in December of 1770, John Adams (played by the excellent Paul Giamatti in the clip below from the fine HBO miniseries, John Adams, based on David McCullough’s Pulitzer Prize-winning biography) offered a now-famous insight: “Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passion, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence.”

Facts, then, can be either “horrid” or “stubborn.” But which? And what of the difference?

David Wootton’s brilliant book, The Invention of Science, makes a compelling case that modernity began late in the 16th Century with the scientific revolution in Europe. In Wootton’s view, this was “the most important transformation in human history” since the Neolithic era and was in no small measure predicated upon a scientific mindset, which included the unprejudiced observation of nature, careful data collection, and rigorous experimentation.

As Wootton explains, knowledge, as it was espoused in medieval universities and monasteries, was dominated by the ancients, the likes of Ptolemy, Galen, and Aristotle. It was widely believed that the most important knowledge was already known. Thus, learning was predominantly a backward-facing pursuit, about returning to ancient first principles, not pushing into the unknown. The great innovation of science was that it built its concept of truth from the “bottom-up,” with its principles discovered rather than pronounced.

Frank Rich is emblematic of the pre-scientific past, when the concept of truth founded upon fact hadn’t yet been invented, or of the post-moderns, for whom the concept of truth is troublesome at best, an oxymoron at worst. For him, facts are “horrid” – obstacles to be overcome or ignored when spinning a favored narrative. Instead, we should aspire to be more like Adams, for whom facts were “stubborn” – realities that need accounting for if we are to obtain the best available approximation of the truth.

We like to think that we are like judges, that we carefully gather and evaluate facts and data before coming to an objective and well-founded conclusion. Instead, we are much more like lawyers (and Frank Rich), grasping for any scrap of purported evidence we can exploit to support our preconceived notions and allegiances. Doing so is a common cognitive shortcut such that “truthiness” – “truth that comes from the gut” per Stephen Colbert – seems more useful than actual, verifiable fact. What really matters is that which “seems like truth – the truth we want to exist.” That’s because, as Colbert explained, “the facts can change, but my opinion will never change, no matter what the facts are.”

We shouldn’t be surprised, then, that when his favored narrative was falsified by the actual people in the photograph, Rich offered a response that provided little insight but, instead, heaping piles of vigorous self-justification. Need I add that the revelation didn’t change his mind or his story, either?

Ironically, the “truthiness” concept “became a lexical prize jewel” for Rich himself (see here, for example), allowing him to criticize his political opponents for offering only “a thick fog of truthiness” such that they presented “a bogus alternative reality so relentless it can overwhelm any haphazard journalistic stabs at puncturing it.” Rich expounded on the idea a number of times in the press and on The Oprah Winfrey Show. He even wrote a book about it. Naturally, he directed the analysis outward rather than inward.

Rich, isn’t it?

Writing op-eds for The New York Times placed Rich in a heady and exclusive echo chamber. Yet it was an echo chamber nonetheless, not to mention a target-rich environment for confirmation bias. Keeping one’s analysis and interpretation of the facts of a story reasonably objective – since analysis and interpretation are required for data to be actionable – is exceedingly difficult in the best of circumstances, even when one has gotten the facts close to right.

Once we have bought-in to a particular narrative, it becomes increasingly more difficult to falsify, even (especially!) when presented with stubborn facts. The more we repeat and reiterate our explanatory narratives, the harder it is to look for “killer” facts that might question or even overturn our preconceived notions and allegiances and to recognize evidence that ought to cause us to re-evaluate our prior conclusions. Facts become less and less stubborn, more and more horrid.

By making it a careful habit skeptically to re-think our prior interpretations and conclusions, we can at least give ourselves a fighting chance to correct the mistakes that we will inevitably make. As with everything in science, each conclusion we draw must be tentative and subject to revision when the facts so demand. Still, and as ever, for too many of us all too often, facts and evidence simply do not matter nearly so much as the stories to which we cling.

The rarest sort of person is one who is capable of seeing, hearing, and synthesizing facts that do not conform to preconceived notions, personal convictions, or conventional wisdom. Consider the opening line of Ursula K. Le Guin’s sci-fi classic, The Left Hand of Darkness: “I’ll make my report as if I told a story, for I was taught as a child on my homeworld that Truth is a matter of the imagination.” Truth is a matter of the imagination in our homeworld, too – partly the imagination to consider other possible stories but, mostly, the imagination to consider and act upon the possibility that we might have things all wrong.*

As with limits in calculus, we may not be able to get all the way there, but we can aspire to the best possible approximation of the truth. What we come to see as (more or less) true can still be highly useful. And the closer to true that it gets, the more useful it can be.

_______________

* The risks of getting it wrong seem to be increasing. We are today a country of competing (and wildly exaggerated) narratives. According to the Yale historian David Blight: “We are tribes with at least two or more sources of information, facts, narratives, and stories we live in.” The United States now is a “house divided about what holds the house up.”

Totally Worth It

Overlooked stories of bravery and adversity commemorate the 75th anniversary of World War II’s end. The most promising thing I read this week. The most terrifying. The most bizarre. The weirdest. The ickiest. The coolest. The most important. The truest. Wow. Who knew?

Benediction

Bruce Springsteen’s 9.11 memorial prayer provides this week’s benediction. “The fundamental thing I hear from fans is, ‘Man, you got me through’ – whatever it is,” the Boss told Rolling Stone about this song in 2002.

We need these stories to preserve the rawness of our emotions about 9.11. Remembering is hard. It is also necessary. And it is good.

Contact me via rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or on Twitter (@rpseawright). Don’t forget to subscribe and share.

Thanks for reading.

Issue 29 (September 11, 2020)