This is the 100th TBL. That doesn’t seem possible, although it started as a pandemic project and the pandemic remains ongoing. The “100” emoji is usually used to express or emphasize achievement, support, approval, and motivation.

Getting to 100 TBLs feels like an achievement. My weekly readership is now well into five figures (although not nearly as big a number as I’d like). Great, right?! It isn’t, really, but it also feels like I’ve been writing TBL a long, long time.

Each of you deserves my thanks for making 100 TBLs possible. Thank you.

If you’re relatively new here, you might check out my personal origin story in TBL #33: “Rhyming Set to Music.”

If you like The Better Letter, please subscribe, share it, and forward it widely. It’s free, there are no ads, and I never sell or give away email addresses.

Thanks for visiting.

Great, Right?!

In the mid-1990s, Procter & Gamble began a secret project to develop a product to eradicate bad smells. PG spent a ton of money developing a colorless, cheap-to-manufacture liquid that could be sprayed on stinky stuff to eliminate the stench. They called it “Febreze.”

To market it, the company formed a team that included a former Wall Street mathematician and various experts on habits to make sure the television commercials accentuated the product’s cues and rewards – the elements that create habits – exactly right.

The first test market commercial showed a woman complaining about restaurant smoke (it was still the 1990s, remember). Whenever she eats there, she says, her jacket ends up smelling like smoke. A friend tells her that if she uses Febreze, it will eliminate the odor. The cue: the dreadful smell of cigarette smoke. The reward: the odor is gone.

The second test ad featured a woman worrying about her dog, Sophie, who always sits on the couch. “Sophie will always smell like Sophie,” she says, but with Febreze, “now my furniture doesn’t have to.”

The ads were put in heavy rotation in several test markets.

The marketing team then sat back, waiting for sales and money to roll in. A week passed. Then two. A month. Two months. Sales started small and got smaller. Febreze was a flop.

The panicked marketers canvassed consumers and conducted in-depth interviews to figure out what had gone wrong. Their big clue came when they visited a woman’s home who seemed like their perfect customer. The house was clean and organized. She was something of a neat freak, the woman explained. But when the PG folks walked into her living room, where her nine cats spent most of their time, the stench was overwhelming. One of them gagged.

A PG researcher asked the woman, “What do you do about the cat smell?”

“That’s not really a problem,” she replied.

Puzzled, the marketer followed up, “So… you don’t smell anything right now?”

“Nope!,” she said. “My cats don’t smell. Great, right?!”

A similar scene played out in dozens of other stinky homes. Febreze wasn’t selling because people didn’t detect most of the bad smells in their lives. Even the worst odors seem to fade with constant exposure. And nobody thinks their sh*t stinks (Stercus cuique suum bene olat, said Montaigne). The “plasticity of disgust,” like “selective perception,” is a real thing.1

In related news, our default status is personal omniscience. We (begrudgingly) concede that we’re wrong about things, perhaps many things. But we can never come up with current examples. We can all recall our past selves and the many mistakes we made and crazy views we held. But that was then, this is now.

We are routinely burdened by the “hubris hypothesis” (for example, as an important study found, physicians “who were ‘completely certain’ of the diagnosis ante-mortem were wrong 40 percent of the time”). Thus, as Martha Deevy, director of the Financial Security Division at Stanford’s Center on Longevity pointed out, “investment fraud works best on highly educated men, who think they’re too smart to be scammed.”

Stephen Jay Gould, the celebrated 20th-century paleontologist, in his most famous work, argued persuasively that prejudiced scientists routinely allowed their social beliefs to color their data collection and analysis, especially when the scientists’ beliefs were particularly important to them. He then went on – inadvertently but conclusively – to prove his thesis in that very work. After all, as Russell Warne argues, “if you believe that the universe is made of cheese, you’re going to build a cosmic cheese whiz detector.”

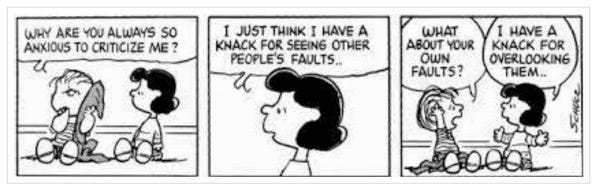

Daniel Kahneman’s memoir of his life’s work, Thinking, Fast and Slow, is built on an amazing foundation: “The premise of this book is that it is easier to recognize other people’s mistakes than your own.”

Or, in the careful prose of scientific research, “people who were aware of their own biases were not better able to overcome them.” As I note repeatedly, we might grudgingly concede that we hold views that are wrong. The problem is in providing current examples. Even worse still is the unfortunate and shocking reality that the smarter and more self-aware we are the more vulnerable we are to these sorts of errors.

Bias blindness impedes us all.

In essence, if we believe something to be true, we quite naturally assume that those who think otherwise are the ones with some sort of problem. Our beliefs are deemed merely to reflect the objective facts simply because we think they are true. Otherwise, we wouldn’t believe them. Then again, “We are not particularly comforted when others assure us that they have looked into their own hearts and minds and concluded that they have been fair and objective.”

Our biases, flaws, and weaknesses are mostly opaque to us. They leave no cognitive trace.

It’s the same sort of thinking that allows us to smile knowingly when friends tell us about how smart, talented, and attractive their children are while remaining utterly convinced as to the objective truth of the amazing attributes of our own kids.

From a large and representative sample, more than 85 percent of test respondents believed they were less biased than the average American. Another study of those who were sure of their better-than-average status found that they “insisted that their self-assessments were accurate and objective even after reading a description of how they could have been affected by the relevant bias.” On the other hand, participants reported their peers’ self-serving attributions regarding test performance to be biased while their own similarly self-serving attributions were free of that bias.

In the “Author’s Message” to his thriller, State of Fear, in which the hero scientist questions climate change, the late Michael Crichton made the point that “politicized science is dangerous,” and then added, “Everybody has an agenda. Except me.”

Really.

When Jane Curtin was asked if the person she was mimicking for a screen role knew that she was the source material, she replied, “I used to do my aunt when I was doing improv, and she always thought I was doing my other aunt.”

George Washington was well aware of his bias blindness, as reflected by his famous Farewell Address, yet another reason for his greatness.

“Though, in reviewing the incidents of my administration, I am unconscious of intentional error, I am nevertheless too sensible of my defects not to think it probable that I may have committed many errors. Whatever they may be, I fervently beseech the Almighty to avert or mitigate the evils to which they may tend. I shall also carry with me the hope that my country will never cease to view them with indulgence; and that, after forty-five years of my life dedicated to its service with an upright zeal, the faults of incompetent abilities will be consigned to oblivion, as myself must soon be to the mansions of rest.”

Lin-Manuel Miranda’s offered a brilliant musical version of that address in Hamilton, with Chris Jackson as Washington. It’s magic.

Bias blindness is the most significant and dangerous bias of all. As Jesus said: “It’s easy to see a smudge on your neighbor’s face and be oblivious to the ugly sneer on your own.”

I have made a great many errors over 100 TBLs. You, dear readers, have pointed out lots of them. Once in a while (although not too often), I have agreed.

Here’s to another 100 TBLs. Thank you all for making the first 100 possible.

Totally Worth It

Feel free to contact me via rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or on Twitter (@rpseawright) and let me know what you like, what you don’t like, what you’d like to see changed, and what you’d add. Praise, condemnation, and feedback are always welcome.

Don’t forget to subscribe and share TBL. Please.

Of course, the easiest way to share TBL is simply to forward it to a few dozen of your closest friends.

If you only read one thing this week, I suggest this. This is the best thing I saw or read this week (backstory here). The best reporting (this, too). The griftiest. The scariest. The sickest. The most damning. The most obvious. The most promising. The most troubling. The most insightful. The most informative. The most interesting. The most insane (more here, here, and here). The most bizarre. The snowflakiest. The funniest. The stupidest. The most sensible. The sweetest (also sweet). The least surprising. The worst karma (the rest of the tragic story here, here, and here). Upside down. Low standards. Culture eats strategy for lunch. If Boston had channeled Adele. It wasn’t merit. Cold. As of 2.2.22, we’re in for six more weeks of winter.

Please send me your nominees for this space to rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or via Twitter (@rpseawright).

The Spotify playlist of TBL music now includes more than 225 songs and about 16 hours of great music. I urge you to listen in, sing along, and turn the volume up.

Benediction

The 100th edition of TBL calls out for a rendition of the “Old 100th,” from Psalm 100.

And, as part of the celebration, let’s bring everybody out to sing the benediction.

To those of us prone to wander, to those who are broken, to those who flee and fight in fear – which is every last lost one of us – there is a faith that offers hope. And may love have the last word. Now and forever. Amen.

Thanks for reading.

Issue 100 (February 4, 2022)

Febreze only became a (massive) success when it tweaked its formula to add perfume and its new ads turned the brand into a pleasant treat at the end of the cleaning ritual, not a reminder that your home stinks.