Almost exactly 50 years ago, on July 1, 1971, John McQuown and his team of academics created the first-ever index fund. Such passive investing tracks the performance of an underlying index of securities, like the S&P 500. It employs broad diversification without stock picking, active trading, or high fees. It was instantly derided by competitors as being “un-American.” Fidelity Chairman Edward Johnson spoke for most of the investment world when he said that he couldn’t “believe that the great mass of investors are going to be satisfied with receiving just average returns.”

Johnson was wrong. As my friend Morgan Housel said, “‘Excellent for a few years’ is not nearly as powerful as ‘pretty good for a long time.’ And few things can beat, ‘average for a very long time.’ Average returns for an above-average period of time lead to extreme returns.”

By 2016, consumers worldwide were pulling more than $300 billion a year out of actively managed funds and investing more than $500 billion a year into index funds. Some $11 trillion is now invested in index funds, up from $2 trillion just a decade ago. And by 2019, more money was invested in passive equity funds than in active funds in the United States.

It isn’t hard to figure out why. Passive outperforms most of the time, often by a lot. For example, fewer than 15 percent of active U.S. large-cap funds beat the market over the previous decade, and it isn’t clear if or how well those outperformers can be ascertained in advance. The great investment debate of my lifetime seems to have been decided. Passive investing has won.

Critics remain and, while they are more than a bit hyperbolic and usually “talking their book,” they aren’t totally devoid of arguments. Shortly before his death in 2019, Jack Bogle, the “godfather of indexing,” warned that index funds’ dominance might not “serve the national interest.” Passive investing leads to less competition and increasing correlation, for example.

However, investors in index funds have done much better than investors in active strategies in the aggregate. By a lot. And that tends to be the bottom line, figuratively and literally.

A mathematical revolution has brought enormous changes to baseball, too. “Moneyball” has carried the day. As the story goes, stats geeks with computers, like those former player and broadcaster Tim McCarver called “drooling eggheads,” outsmarted and outmaneuvered the stupid yet arrogant “baseball men” who ran our most traditional sport at the professional level and who thought they knew all there was to know about the game.

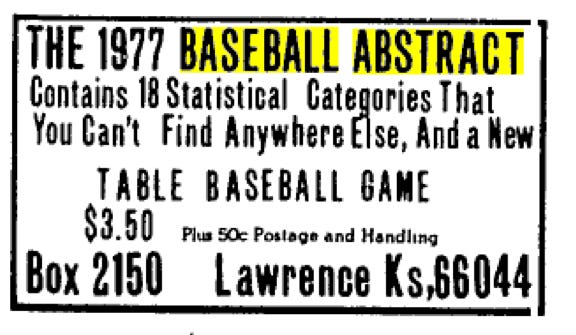

This paradigm shift began 44 years ago with a really smart security guard named Bill James.

Only 75 people bought that first Baseball Abstract. I was an early adopter. Today, analytics drive Major League Baseball. Every MLB organization now has an analytics department filled with full-time data scientists with advanced degrees in computer science, physics, mathematics, and related disciplines.

That’s because good analytics lead to winning more games.

They do so with “maximum effort” pitching, which means higher velocity, more foul balls, fewer innings pitched, more pitches per at bat, more pitching changes, and more strikeouts. They do it by adjusting swing planes to get higher launch angles, more extra base hits, and more home runs with fewer hits overall, fewer ground balls, fewer bunts, and fewer balls in play.

A century ago, about 25 percent of plate appearances resulted in hits with fewer than 10 percent strikeouts. Today, there are more whiffs than hits. Thus, aesthetics have suffered and more managers are pouring through binders in dugouts, but doing these sorts of things increase the likelihood of winning.

At the level of personnel, it means locking down generational talent early because it is in such short supply and cannot readily be replicated. See, e.g., Wander Franco and Fernando Tatis, Jr.

In baseball, it’s “go big or go home.” In investing, not so much. This week’s TBL will take a look at that general option and consider when it makes sense to diversify your bets and when you should “go big.”

If you like The Better Letter, please subscribe, share it, and forward it widely. It’s free, there are no ads, and I never sell or give away email addresses.

Thank you for reading.

Going Big

We humans are both terrified and entranced by extreme events. In the financial world, for example, we routinely overpay both for insurance and for lottery tickets (literal and figurative). There is good reason for that generally, as Morgan Housel has explained (emphasis in original).

“Long tails drive everything. They dominate business, investing, sports, politics, products, careers, everything. Rule of thumb: Anything that is huge, profitable, famous, or influential is the result of a tail event.”

Unfortunately, we often fail to deal well with extreme events.

When I was a kid, my hometown had an egg hunt on the Saturday before Easter. Hundreds of multi-colored plastic eggs were hidden over a large area. When discovered, each could be turned in for a candy bar except for one golden plastic egg, which could be redeemed for a chocolate Easter bunny. The rules prohibited holding on to an egg while searching for the grand prize. I was a rule follower who was determined to “go for the gold.” When I didn’t find it, I was left candy-less.

I “overpaid” for my “lottery ticket.” It was a mistake to “go for it all.”

Assume there were 500 eggs that offered candy bars with a given value (x) and the golden egg was (generously) worth 10(x). That means the expected value of the pool of eggs was 1.02(x) per egg. Had I “settled” for an ordinary egg – I passed up dozens – I would have gotten nearly all the value I could have expected: 1(x) out of 1.02(x). Instead, I got no candy at all. In effect, I bought the lottery ticket but should have taken out insurance.

In this instance, the right choice reflects an “index mindset,” as described by John Luttig. Very broadly speaking, it favors average results over extreme ones, a bird-in-hand over two in the bush, relative over particular truth, function over form, quantity over quality, mandate over merit, efficiency over exploration, passivity over action, predictability over tails, determinism over freedom of choice, mistake avoidance over smart decisions, evolution over revolution, adaptation over reformation, safety over risk, diversification over concentration, preservation over creation, velocity over due diligence, optionality over decisiveness, the general over the specific, and growth over profit. It is the correct default for investment in public markets but is often dangerous in other contexts.

This mindset increasingly dominates our thinking and our culture. It can feel like Game of Thrones.

Trading 101 says to avoid crowded trades. The index mindset seeks out crowded trades and counts on capital flows continuing to crowd in, supporting the trade and the choice.

Venture capital is today mostly an index bet for most investors – buying into a broad basket of start-ups based largely upon standard valuation measures, favoring momentum over value. It is, as Luttig points out, “implicitly a bet on capital flows more than intrinsic company value.”

Not everybody should, or even can, make an indexed bet, however. Founders, innovators, and disruptors generally can’t afford to index their markets. Intense, company-level competition won’t allow it. As Keith Rabois explained, “product market fit is forged, not discovered.”

For my money, this general quandary is demonstrated best by looking at NFL quarterbacks, the most important players in any sport. In today’s NFL, it is possible to win a Super Bowl without a great (“franchise”) quarterback, but it’s rare enough that no team should want to try.

Nearly all Super Bowl winning QBs in the salary cap era (from 1994) were outstanding (roughly top quartile overall). The exceptions were (a) two excellent QBs who won Super Bowls in years that weren’t their best (2007 season Eli Manning and 2008 season Ben Roethlisberger), (b) two QBs who had stellar playoff runs before mean reverting (Joe Flacco and Nick Foles), and (c) the only two true outliers (Brad Johnson and Trent Dilfer).

Due to salary cap restrictions and the value of franchise quarterbacks, it is generally better to draft a great quarterback than to buy one on the (relatively) open market. Of course, that’s much easier said than done.1

Troy Aikman, Steve Young, John Elway, Peyton Manning, and Eli Manning were first overall picks who won Super Bowls. However, over that same period, 19 quarterbacks who were first overall picks have not (at least not yet) won championships. And these as yet non-winners include some spectacular busts (JaMarcus Russell, ladies and gentlemen), as Cleveland Browns fans understand particularly well.

Of the QBs who have won Super Bowls in the salary cap era, only Kurt Warner (undrafted), Brad Johnson (9), Tom Brady2 (6), Russell Wilson (3), Nick Foles (3, but subbing for a 1 in Carson Wentz), Drew Brees (2), and Brett Favre (2) were not first round picks. Passer Ratings decline with every round of the draft except the sixth, the numbers for which are skewed by Brady. But only about half of first round QBs “make it” in a meaningful way.

What all this means is that NFL draft evaluators generally recognize who won’t be a great NFL quarterback but not who will be. In other words, they can usually eliminate those who aren’t good enough but don’t differentiate well among those who might be good enough.

NFL teams recognize the need to “go big” for a franchise QB. Every year, teams select quarterbacks early in the draft, hoping against hope that they will catch lightning in a bottle. They fail much more often than they succeed.

“Going big” is a high variance choice and, in many endeavors, is a net loser overall. Moreover, even when the math provides a net win, going big can be a mistake.

Suppose you are offered a chance to enter a coin-flipping contest that costs a dollar to enter where heads pays +50 percent while tails “pays” -40 percent. With sufficient flips and a fair coin, it seems that the net result should be positive. However, that only happens with a very large number of players pooling their resources. As Ole Peters has shown, the vast majority of players will crap-out on account of the “arithmetic of loss.” Positive outcomes are concentrated in a tiny number of lucky players who amass huge sums (that’s how VC works, for example). Accordingly, in that setting, and from an investment standpoint, it only makes sense to participate if you can “index” and play a very large number of games.

Creators, of course, must roll the dice alone.

The S&P 500 has averaged roughly 10 percent per annum returns since inception, including dividends. But very few years have been close to average (annual S&P 500 returns have been between 8 and 12 percent only four times since 1928) and very few component companies within the index provide “average-ish” returns. For example, Apple, Alphabet, Microsoft, Amazon, and Tesla have, together, gained $6.5 trillion in value since their March 2020 lows. Apple alone has gained an astonishing $1.85 trillion in value over just 433 trading sessions — an average increase of well over $4 billion per trading day. And Morgan Stanley analyst Katy Huberty says Apple is worth another $25 per share (from roughly $175 to $200).

Indexing means we own the losers, too, but we also own the big winners.

The index mindset increasingly dominates our cultural milieux. Diversification and risk avoidance now generally rule the day.

In philosophy, we’ve seen a shift from a capital-T Truth to a multitude of small-t truths – “your truth” and “my truth” – within a moral relativism. In physics, we’ve seen a shift from a certain Newtonian physics to probabilistic quantum mechanics.

In politics, globalism replaced nationalism after World War II. Fewer and fewer of us accept the idea of American exceptionalism anymore.

The arts should be well positioned to reject the index mindset both in the sense that it thinks we can recognize good over bad, great over good, and that Truth and “true love” are worth seeking and even dying for. Yet we index there, too. We are oh so eager to proclaim that those who don’t learn from the past are doomed to repeat it – right before watching a movie with a numeral in the title. For the third time.

As Jennifer Aniston has explained, “the industry isn’t secure enough to say, ‘Yeah, let’s try it.’”

Private life has also become indexed. Just a few decades ago, marriage was the rule and marriage at a young age was common, with partners committed until death parted them. Not anymore. Today, marriage comes six years later and schooling lasts five years longer. Tinder and other dating apps allow people to diversify their relationship capital across an index of dozens of partners while avoiding a commitment to marriage and a family. “Weddings” within the metaverse or a video game are increasingly a real thing, but that reality doesn’t yet include legality.

Even college and career choices have become indexed and hedged. The more our decisions are algorithmically derived, the more humanity will be required to stand out. The index mindset is comfortable – avoiding decisions requires the least amount of effort. But if you index across every domain, you lose any differentiating features, becoming little more than an average of everyone else.

Because it emerges in liquid markets, and because technology supercharges liquidity generally, the index mindset won’t be going away. Ever-increasing liquidity is an enemy of community. The question is when and if you should participate. The short answer is “almost surely a lot less than you do now.” I say, generally, “Go for it. Go big or go home.”

Totally Worth It

Bob Dylan: “Sam Cooke said this when told he had a beautiful voice: He said, ‘Well that’s very kind of you, but voices ought not to be measured by how pretty they are. Instead, they matter only if they convince you that they are telling the truth.’”

Feel free to contact me via rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or on Twitter (@rpseawright) and let me know what you like, what you don’t like, what you’d like to see changed, and what you’d add. Don’t forget to subscribe and share.

Of course, the easiest way to share TBL is simply to forward it to a few dozen of your closest friends.

Please send me your nominees for this space to rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or via Twitter (@rpseawright).

This is the best thing I saw or read this week. The craziest. The stupidest. (other candidates here, here, here, and here). The saddest (perhaps not for the reasons you think). The wildest but least surprising. The funniest. The most interesting. The most predictable. The most disappointing. The most disgusting. The most remarkable (check it out here). This is real inflation. Wow. Grammar for the win. It’s a Wonderful Life for real.

On average, U.S. commuters are on pace to lose 36 hours to congestion in 2021, 10 hours more than in 2020 but 63 hours fewer than in 2019.

The Spotify playlist of TBL music now includes more than 200 songs and about 15 hours of great music. I urge you click on the link immediately below to listen … and turn the volume up. Way up.

Benediction

Pie Jesu, pie Jesu, pie Jesu, pie Jesu | Qui tollis peccata mundi | Dona eis requiem, dona eis requiem | Pie Jesu, pie Jesu, pie Jesu, pie Jesu | Qui tollis peccata mundi | Dona eis requiem, dona eis requiem | Agnus Dei, Agnus Dei, Agnus Dei, Agnus Dei | Qui tollis peccata mundi | Dona eis requiem, dona eis requiem | Sempiternam | Sempiternam | Requiem

Merciful Jesus, merciful Jesus, merciful Jesus, merciful Jesus | Father, who takes away the sins of the world | Grant them rest, grant them rest | Merciful Jesus, merciful Jesus, merciful Jesus, merciful Jesus | Father, who takes away the sins of the world | Grant them rest, grant them rest | Lamb of God, Lamb of God, Lamb of God, Lamb of God | Father, who takes away the sins of the world | Grant them rest, grant them rest | everlasting | everlasting | Rest

To those of us prone to wander, to those who are broken, to those who flee and fight in fear – which is every last lost one of us – there is a faith that offers hope. And may love have the last word. Now and forever. Amen.

Thanks for reading.

Issue 92 (December 10, 2021)

I’m only using data from the salary cap era (1994 to date) to make for a fairer basis for evaluation.

There were 198 players and six quarterbacks (Chad Pennington, Giovanni Carmazzi, Chris Redman, Tee Martin, Marc Bulger, and Spergon Wynn) selected in the 2000 draft before Tom Brady, who became the GOAT and is this season’s likely MVP, again, at age 44.