Revenge of the Nerds

This edition of TBL looks at the Moneyball revolution.

If you like The Better Letter, please subscribe, share it, and forward it widely.

NOTE TO SUBSCRIBERS: Some email services may truncate TBL. If so, or if you’d prefer, you can read it all online here. If it is clipped, you can also click on “View entire message” and you’ll be able to view the entire missive in your email app.

Thanks for reading.

Revenge of the Nerds

Baseball’s analytics revolution – which became an analytics revolution in all sports and, in no small measure, in the culture at large – owes its existence to a really smart security guard from Kansas

In 1977, Stokely-Van Camp (the pork and beans people) night watchman Bill James created a 68-page “book” of mimeographed, single-spaced sheets stapled together, called Baseball Abstract (featuring “18 Statistical Categories That You Can’t Find Anywhere Else”), advertised in the back pages of The Sporting News, then the media outlet for baseball fans. Only 75 people responded to that first ad, although Norman Mailer was one of them. So was screenwriter William Goldman (“nobody knows anything”).

It was hardly an auspicious beginning. But I was an early adopter. So were famous commodities trader John Henry, who would later go on to buy the Boston Red Sox, and Theo Epstein, who Henry would hire as the youngest General Manager in baseball history (more on this later).

This seemingly minor event marked the advent of a new era in baseball research. James’ approach, which he termed sabermetrics in homage to the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR, founded in 1971), set out to analyze baseball scientifically, to determine why teams win or lose. Along the way, he got to debunk lots of traditional baseball dogma, what James called “baseball’s Kilimanjaro of repeated legend and legerdemain.”

James not so modestly wrote that he wanted to approach baseball “with the same kind of intellectual rigor and discipline that is routinely applied, by scientists great and poor, to trying to unravel the mysteries of the universe, of society, of the human mind, or of the price of burlap in Des Moines.” He merged that scientific rigor with a poet’s sensibilities. His approach was in stark contrast to that of the traditionalists, “an assortment of half-wits, nincompoops, and Neanderthals…[who] are not only allowed to pontificate on whatever strikes them, but are actually solicited and employed to do this.” Best of all, James made careful statistical analysis accessible and interesting while also seeking to be practical in a way fans could appreciate.

James’ pioneering approach began quietly, but slowly built a following. The Baseball Abstract books by James — which I read as carefully as I read the backs of baseball cards as a kid — were the modern predecessors to the sports analytics movement, which has since spread to all major sports.

James clearly demonstrated, using straightforward empirical data infused with inexorable logic and practicality, that many of the supposed truisms of baseball were false. He showed, for example, that starting pitchers have no effect on attendance, that catchers have a great effect on base stealing, that sacrifice bunts are usually counterproductive, and that ballplayers peak in their late 20s (rather than the early 30s as had been supposed).

What James also demonstrated, indirectly but no less clearly, that analytics – the judicious use of statistical data to support evidence-based decision-making – provide a reservoir of untapped information that could be turned into improved performance and a competitive advantage.

Regular readers will surely intuit why that didn’t happen, at least not right away.

As per the scientific method, we should always hold our views of the truth lightly and tentatively, subject to more and better information and arguments. Changing our minds for those reasons (as opposed to mere expediency) is a good, useful, and desirable thing. As Jeff Bezos of Amazon insightfully expressed it, people who are right a lot of the time are people who change their minds a lot. This approach is depressingly rare.

“For desired conclusions,” Thomas Gilovich explained, “it is as if we ask ourselves ‘Can I believe this?,’ but for unpalatable conclusions we ask, ‘Must I believe this?’” With the former, we’re seeking permission to believe, and accept any remotely plausible scrap of support, sometimes less. With the latter, we’re looking for an escape route. Which we can’t wait to use.

That reality provides a very good explanation for why people change their minds so seldom that the claim it never happens — especially about things we care about — is only modest hyperbole. Or, as Daniel Kahneman says, it’s right “to a first approximation.”

Accordingly, the “traditional baseball men” ignored Bill James. For years. Even though it might help them win. A sabermetrics movement developed and flourished among baseball fans. But, among professionals? Mostly crickets.

That’s because science only advances one funeral at a time, as the great physicist and Nobel laureate Max Planck understood.

“A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it.”

After many years of ignorance, change began slowly and at the margins as new faces appeared on the baseball landscape. Sandy Alderson, who came to the Oakland A’s with no baseball background, hired Billy Beane when his playing career ended. He encouraged Beane to be creative in his analysis of players, to continue Alderson’s experiments with sabermetrics, and continued his encouragement after naming Beane as GM in 1997. Beane obliged. Because he had so little money to work with, his analytical approach was born of necessity.

In 2001, one of Beane’s like-minded deputies, J.P. Ricciardi, was hired to run the Toronto Blue Jays.

In 2002, John Henry became lead owner of the Boston Red Sox. He had made his fortune as a commodities trader on Wall Street and was already a Bill James devotee, as noted. When Billy Beane turned him down, Henry hired James fanboy Theo Epstein, who was able to put real money behind James’ ideas, even hiring James as a senior consultant.

Baseball is our most change-averse sport, bound like no other to its quirky traditions and rules, both official and unofficial. Today’s game would still be recognizable to baseball fans from a century ago. But change was a-comin’.

Twenty years ago, when Michael Lewis’ Moneyball hit bookstores, the baseball “market” had already started to move away from traditional scouting, but it turbocharged the changes and dramatically changed the way fans look at baseball.

Living next door in Berkeley, within shouting distance of the Oakland Coliseum, where they played, Lewis became fascinated with the unlikely success of the Oakland A’s and wrote Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game. It became a huge bestseller and accelerated the statistical disruption of the National Pastime.

Moneyball focused on the 2002 season of the Oakland Athletics, a team with one of the smallest budgets in baseball. Sabermetrics was then pretty much the sole province of stats geeks, alleged to be living in their parents’ basements. At the time, the A’s had lost three of their star players to free agency because they could not afford to keep them.

A’s General Manager Billy Beane was in a very tough spot, which both allowed and spurred him to go “all in” on the James approach. Beane armed himself with reams of performance and other statistical data, his interpretation of which, heavily influenced by James (although taught to him by A’s consultant Eric Walker), was routinely rejected by “traditional baseball men,” including many in his own organization. Not coincidentally, Beane was also armed with three terrific — according to both traditional and newfangled measures — young (and thus cheap) starting pitchers, not to mention AL MVP Miguel Tejada, Eric Chavez, and Jermaine Dye.

Beane used sabermetrics not to compile his roster so much as to complete his roster with otherwise undesirable players on the cheap to create a team that proceeded to win 103 games and the division title largely because the newly acquired players’ true value was much higher than traditional measures recognized.

It’s not like baseball was never innovative. In the 1920s, for example, Branch Rickey created the modern farm system when he was running the St. Louis Cardinals. He couldn’t buy Babe Ruth, so he tried to grow somebody like him. And, it’s not like nobody knew better data was needed.

“Would a system that placed nickels, dimes, quarters, and 50-cent pieces on the same basis be much of a system whereby to compute a man’s financial resources?”

So wrote sportswriter F.C. Lane about batting average, then the most popular statistic for judging hitters, in 1916.

“Pretty poor system, isn’t it, to govern the most popular department in the most popular of games?”

Still, baseball wasn’t interested in nerds calling the shots.

Beane’s pedigree as a former top draft choice and a Major League player (albeit a not very good one), along with the A’s lack of money and the freedom his bosses gave him, meant that he had some space to maneuver. And maneuver he did.

The crucial insight of Moneyball, which came from Walker, was a “Mungeresque” inversion. In baseball, a team wins by scoring more runs than its opponent. Walker’s epiphany was to invert the idea that runs and wins were achieved by hits to the radical notion that the key to winning is avoiding outs (bonus points to you if you’re now thinking about the Charley Ellis classic book on investing, Winning the Loser’s Game). That led Beane to “buy” on-base percentage cheaply because the “traditional baseball men” overvalued hits but undervalued OBP, even though it doesn’t matter how a batter avoids making an out and reaches base.

Because Beane focused on the problem, rather than a presumed, “consensus” solution, he was able to manufacture a competitive advantage for his team.

Therefore, the crucial lesson of Moneyball was that Beane was able to find value via underappreciated player assets (some assets are cheap for good reason) by way of an objective, disciplined, data driven (Jamesian) process. In other words, as Lewis explained, “it is about using statistical analysis to shift the odds [of winning] a bit in one’s favor” via market inefficiencies.

As Assistant GM Paul DePodesta said, “You have to understand that for someone to become an Oakland A, he has to have something wrong with him. Because if he doesn’t have something wrong with him, he gets valued properly by the marketplace, and we can’t afford him anymore.”

Accordingly, Beane sought out players that he could obtain cheaply because their actual (statistically verifiable) value was greater than their generally perceived value. Despite the now widespread use of James’ approach, broadly construed, smart baseball people are still finding under-appreciated values and lunkheads are still making big mistakes.

Moneyball became a huge bestseller and a cultural phenomenon. Reviewers loved it, calling it the most influential baseball book ever. Businesspeople loved it, finding multiple applications and providing Beane with a steady diet of speaking invitations and interview requests.

Moneyball focused on value assessment, and that’s something that’s germane whether you’re running Tesla or Goldman Sachs or the Oakland A’s. Accordingly, “Moneyball” became a term of art, with frequent usage in the press and the popular culture.

It has turned into a placeholder for almost any kind of strategy that uses an analytical style of thinking to solve a problem.1

TL;DR: Baseball’s establishment could no longer ignore sabermetrics.

When ignoring Bill James and his work was no longer possible, thanks to Moneyball, baseball’s insiders, and their enablers in the press, turned to ridicule. Consider, for example, former player turned broadcaster Hawk Harrelson’s refusal to accept the analytics revolution.

Or, consider how newspaper columnist Bill Plaschke greeted the Dodgers’ hiring of Paul DePodesta, made famous by Moneyball, as GM. “The Dodgers have a new face, and it is dabbed in Clearasil,” wrote Plaschke2 in The Los Angeles Times. “The Dodgers have a new voice, and it speaks in megabytes. Meet GeneralManager.com, otherwise known as Paul DePodesta, a 31-year-old computer nerd who was hired Monday to rid the Dodgers of their, um, virus.”

Some of these old-time insiders still ridicule empirical reality. Perhaps Hall-of-Famer Goose Gossage said it best.

“I’ll tell you what has happened, these guys played rotisserie baseball at Harvard or wherever the [bleep] they went and they thought they figured the [bleeping] game out. They don’t know [bleep].

“A bunch of [bleeping] nerds running the game.”

That’ll show ’em, Goose.

However, the ridicule didn’t work. “Moneyball” went mainstream. Advanced analytics were nonexistent for years after their lessons were demonstrated. The movement within MLB was born of necessity in Oakland. After Moneyball, it moved from “subterranean and emergent” to “omnipotent and ubiquitous.”

On account of the popularity of Moneyball, the Bill James approach was put on display for everyone to see. The success of Moneyball (and the Oakland A’s) meant that the “traditional baseball men” could no longer readily ignore it, especially because Wall Street people (like John Henry) dedicated to using analytics and data-driven processes had started to buy baseball franchises.

Owners read it. Fans read it. And everybody who read it wondered, often loudly, why their team wasn’t using the best evaluation tools.

After Moneyball, the victory of sabermetrics over the baseball establishment was assured, even if the “traditional baseball men” didn’t know it yet.

“Eventually, things were going to shift,” Cubs president Jed Hoyer said, “but I thought it put that in fast-forward. The book comes out, a lot of owners read the book and realized they were doing the things that a handful of teams were doing and it just microwaved the process of change in those years after the book came out. In the next five years, there was so much change because, all of a sudden, owners were driving that change.”

Theo Epstein sealed the deal.

Epstein, hired as a whiz-kid GM at age 28, used the same approach (with a lot more money) to overcome some of the most prominent failures in Major League history – putting together teams to win the World Series for the Red Sox (in 2004, for the first time in 86 years, and again in 2007) and then for the Chicago Cubs (in 2016, for the first time in 108 years). He started out in Boston as an unconventional general manager, a neophyte swimming against the current. By 2011, with two titles, he left Boston having altered the course of the river.

By the time Moneyball, the movie, came out, also in 2011, every Major League team used advanced statistical measures. And today, MLB general managers and executives don’t look like the baseball men of yesteryear. They look like investment bankers in chinos. Some even used to be investment bankers.

By just 2006, Time magazine named James as one of the 100 most influential people in the world. Epstein described James’ impact on the game to Time.

“The thing that stands out for me is Bill’s humility. He was an outsider, self-publishing invisible truths about baseball while the Establishment ignored him. Now 25 years later, his ideas have become part of the foundation of baseball strategy.”

In fact, Epstein hired James to a consulting position he still holds, as a kind of chief ideas and culture officer for the Red Sox, to keep the team pointed in the right direction.

The bottom line is that baseball analysis has become far more objective, relevant and useful largely because of Bill James. Most importantly, the James approach works (if not as well as some might hope — there are other factors involved, as James readily concedes).

Statistical analysis and advanced technology have allowed teams to ascertain what “launch angles” improve power-hitting, the change in run-scoring probabilities if fielders are shifted from their traditional slots, or the most effective way to change pitchers. The most impactful rules changes in baseball history were implemented last season to try to deal with what sabermetrics have wrought, a less entertaining game3 of fewer hits and runs, defensive shifts, more pitching changes, more breaking pitches, more strikeouts, and greater fastball velocity.

Evidence-based baseball has won the war (and championships). It has even made its way into baseball broadcasting (finally). Despite years of ostracism and ridicule, the reality revolution was accomplished with shocking speed once it started and today seems complete. Google thus uses baseball analytics to illustrate the data driven decision-making process to which the company aspires.

Overall, baseball is pretty efficient. Generally, despite some glaring exceptions, rich teams do better than poor teams. Sabermetrics provides an opportunity for the “have nots” to compete.

When I first read Moneyball, I wondered why Beane had given Lewis so much access and wondered if Beane was angry that his process was revealed for all to see.

Billy Beane was angry about Moneyball, but not because his “secrets” were disclosed (he didn’t think anybody in baseball would read it). He was mad because his mother found out how often he said “f*ck.”

Theo Epstein was also upset, but the focus of his displeasure were the revelations about process. Lewis had visited him in Boston while researching the book, but Epstein remained mum. “I can’t believe Billy is letting him write this book,” he told his colleagues. “He's handing out the blueprint.”

“It just seemed that [the book] would take a nuanced idea – while not a great secret, because Branch Rickey was using a lot of it a half century ago and Bill James had been writing about it for decades – and make it mainstream pretty quickly.

“The book hit The New York Times best-seller list. People who own baseball teams read The New York Times best-seller list. So they started asking questions about the processes their front offices were using, and it changed things really quickly.”

Epstein was prescient. The easy competitive advantage of the early adopters is largely gone, replaced by some proprietary insights and new ideas, mostly at the margins. Inefficiencies are harder to find and are more fleeting. Teams are all trying to figure out how to keep pitchers healthy and how to draft more effectively, with limited success. Today, Epstein explains, “you’re not going to have the most success with the most obvious, readily available information.”

Quants can arbitrage away the advantages in factors and statistics almost as soon as they’re discovered – in markets and in baseball – and Moneyball shows the A’s arbitraging the mispricing of baseball players. But good trades get crowded and are no longer good trades, in much the same way that, in the investing world, good trades get crowded and, on account of the paradox of skill, investors can get better yet find it harder to outperform.

Warren Buffett’s Berkshire-Hathaway earned a compound annual gain 19.8 percent from 1965 through 2022, compared with 9.9 percent for the S&P 500. That’s an overall total return of an astonishing 3,787,464 percent versus “just” 24,708 percent for the benchmark. That’s why Buffett is widely regarded as the greatest investor of all-time.

Over the most recent 20 years (2003-2022), the S&P 500 delivered a 9.80 percent annualized return while Buffett came in a touch lower at 9.75 percent. That’s still great, but even Warren Buffett hasn’t been able to beat the market over the past 20 years.

Ongoing and consistent outperformance, in baseball, the markets, and in life, is staggeringly difficult. Prepare and respond accordingly. We get better and keep getting better at things by being responsive, observant, and applying what we’ve learned. Over and over again.

Totally Worth It

A few hours ago, I met Tim Alberta and heard him talk about his important new book, The Kingdom, the Power, and the Glory: American Evangelicals in an Age of Extremism, released this week, with Jonathan Swan of The New York Times. I highly recommend it. You may read excerpts here and here.

Feel free to contact me via rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or on Twitter (@rpseawright) and let me know what you like, what you don’t like, what you’d like to see changed, and what you’d add. Praise, condemnation, and feedback are always welcome.

You may hit some paywalls herein; many can be overcome here.

This is the best thing I read in the last week. The scariest. The sweetest. The saddest. The coolest. The hardest to believe. The most heartwarming. The most dangerous. The most sensible. The best thread. Rock on. Twenty first times. Horror story. The “capability gap.”

Please send me your nominations for this space to rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or via Twitter (@rpseawright).

The TBL Spotify playlist, made up of the songs featured here, now includes over 270 songs and about 19 hours of great music. I urge you to listen in, sing along, and turn up the volume. The TBL Spotify Christmas playlist is here.

My ongoing thread/music and meaning project: #SongsThatMove

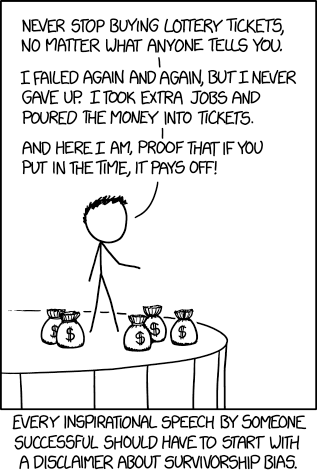

Source: xkcd

Benediction

This week’s benediction is provided by the two-time Grammy-winning jazz singer, Gregory Porter, singing gospel. And singing it great.

We live on “a hurtling planet,” the poet Rod Jellema informed us, “swung from a thread of light and saved by nothing but grace.”

To those of us prone to wander, to those who are broken, to those who flee and fight in fear – which is every last lost one of us – there is a faith that offers grace and hope. And may love have the last word. Now and forever. Amen.

As always, thanks for reading.

Issue 161 (December 8, 2023)

What Lewis captures in his book – the revenge of the nerds – mirrors what has been happening throughout the American economy (see, e.g., Fredrik deBoer’s The Cult of Smart). Baseball, the history of which is anything but intellectual, is now dominated and run by intellectuals.

Be sure to read this classic skewering of Plaschke.

Analytical approaches to football opened up the passing game, and in basketball, heavily increased usage of the 3-point shot. But, in baseball, the focus on perfection and logic eventually turned the game into a more static, more boring sport.

Bob, this is an awesome piece. Thank you.

This is great and every sports commentator should be forced to read it. I always get frustrated when people misunderstand Moneyball or reference it incorrectly. When people use Moneyball and the words Dodgers or Yankees in the same sentence they probably are missing the point. The A’s maximized wins at minimal cost. Spending $240 million on a free agent with a high OBP is definitely not Moneyball. Spending $500k on a washed up player who still has a high OBP is Moneyball at its finest.