Those of us called upon professionally to write about market performance in 2022 as the year ends are necessarily struggling for the right verbiage. Words like “challenging” and “difficult” are sure get heavy play. That’s because, in language as plain as I can make it, pretty much every market and sector has had a very bad 2022.

As I write this TBL, the S&P 500 is getting crushed and (using very rough numbers) is down 18 percent year-to-date. The Dow is down 8.5 percent. The Nasdaq is down a dreadful 31 percent. The Russell 2000 is off 21 percent. Value (S&P 500 Value Index) is down less than 3 percent but growth (S&P 500 Growth Index) is down 25 percent.

Meanwhile, bonds have been suffering what is probably their worst year ever. The benchmark 10-year U.S. Treasury note has seen its yield jump about 200 basis-points to around 3.5 percent and the yield curve is now inverted as two-year-notes are yielding about 4.25 percent and 6-month T-bills are yielding almost 4.75 percent. The Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index has lost more than 11 percent so far this year.

Based on the above, nobody should be surprised that 2022 looks like it will be the worst year for the classic 60:40 portfolio since 1937’s -22 percent.

Things are no better overseas. Losses in the MSCI EAFE Index are approaching 12 percent YTD. The MSCI Emerging Markets Index is off nearly 20 percent. At the country level, in Europe, the MSCI France Index is down 10 percent, Italy 12 percent, Germany 20 percent, and the U.K. “only” 1.5 percent. In Asia, the MSCI China All Shares Large Cap Index is down 23 percent, Japan 15 percent, and India 5 percent.

The only good news, broadly speaking, is in the commodity space. Gold is off about 2 percent YTD, but the oil and gas sector has seen gains approaching 50 percent.

In the aggregate, this news is no fun at all. Still, it’s not a problem for long-term investors.1 So let’s put the ugliness into context to understand why.

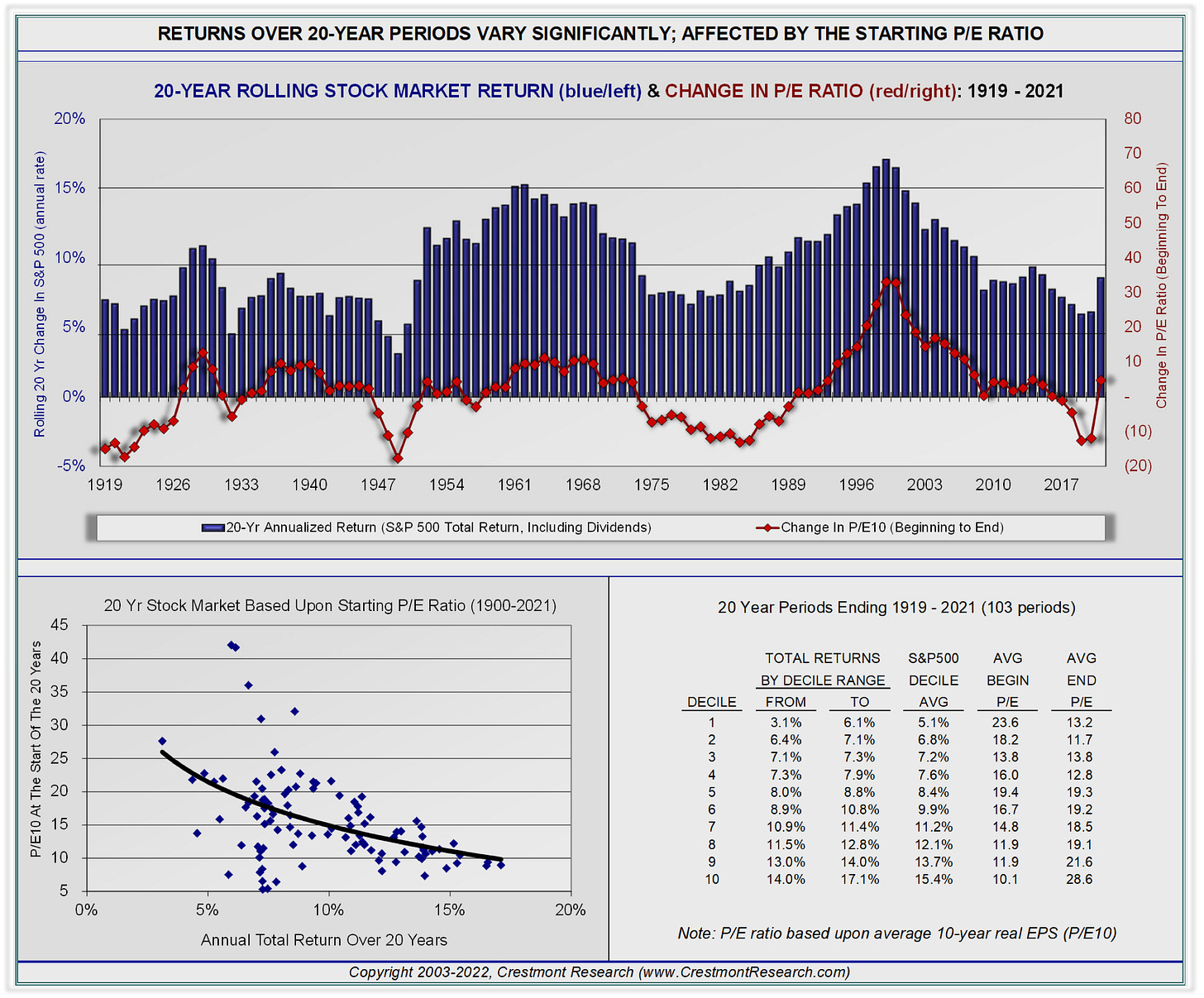

Source: Crestmont Research

Over the past 50 years (1972-2021), the S&P 500 has provided an excellent annualized total return of 9.4 percent, but the results are heavily skewed. In 19 of those years, the index gained more than 20 percent. Returns were 10-20 percent 13 times and 0-10 percent nine times. Losses of up to ten percent were suffered four times, 10-20 percent two times (with 2022 likely making it three), and more than 20 percent three times.

Bonds have provided lower returns with much lower volatility over that same period. Depending upon the index, bonds have generally offered 4-6 percent per annum historically, but appear headed for their worst year ever in 2022.

Over the past 50 years (1972-2021), the benchmark 10-year U.S. Treasury note has returned as much as 32.81 percent in a calendar year (1982) and lost as much as 11.12 percent (2009). The 10T has gained more than 20 percent five times, between 10-20 percent 12 times, and between 0-10 percent 24 times over that same period. It has lost from 0-10 percent 8 times and more than 10 percent just once. Almost certainly (with two weeks left in the year), the 10T’s losses in 2022 will exceed that low-water mark. Already, the 12 months through October ranked as the worst such period ever recorded, using data going all the way back to 1794.

The alternative investment space, however defined, is opaquer and generally exists over a much shorter duration. The FTSE Nareit All REITs Index of real estate investments has returned 8.01 percent per annum over the last 25 years. The Morningstar Hedge Fund Index has returned 6.93 percent per annum over the past 10 years. The HFRI Composite Index has returned 4.81 percent per year over the past five years. Based upon last week’s TBL, those hedge fund numbers sound high.

The clearest lesson here is that stocks are vital for long-term investors. Al Capone is said to have claimed that he robbed banks because that’s where the money is. Good long-term investors buy stocks because that’s where the best returns are.

Using very rough long-term return numbers (9.5% for stocks; 5% for bonds; 8 percent for real estate; and 6% for hedge funds), $10,000 invested for 30 years in stocks turns into about $173,000 while bonds yield $45,000, real estate $110,000, and hedge funds $60,000.

That’s an enormous disparity.

Here’s an important corollary: Pain is part of the process. That pain is the subject of this week’s TBL. If you like The Better Letter, please subscribe, share it, and forward it widely.

NOTE: Some email services will likely truncate this TBL. If so, or if you’d prefer, you can read it all here. If it is clipped, you can also click on “View entire message” and you’ll be able to view the entire post in your email app.

Thanks for reading.

Pain is Part of the Process

In his most successful song, Frank Sinatra crooned: “Regrets? I’ve had a few. But then again, too few to mention.” Obviously, he wasn’t talking about the markets. Every investor has regrets.

I can’t begin to count the number of times I have heard people ruing “the one that got away.”2 And by that, I don’t mean a love interest. I mean an investment. The lament usually takes the form of an investment opportunity not taken that turned out great or a great investment that was sold too soon – usually much too soon.

If only they’d known then what they know now.

Especially in times like these, when markets are difficult and not giving us what we want when we want it, I am regularly and invariably asked – longingly – for “the next Amazon,” or something strikingly like it. The thinking is typically that if only these folks could just smoke out the next great whatever company, all would be well and investing would be easy.

If only.

Good investing is never easy.

Finding “the next Amazon” is really, really hard. Hendrik Bessembinder, professor of finance at Arizona State University, evaluated the lifetime returns of every U.S. common stock traded on the New York and American stock exchanges and the Nasdaq from 1926-2019. He discovered that the 86 top-performing stocks (Amazon and stocks like it), less than one-third of one percent of the total, collectively accounted for more than half of the total wealth creation of the entire public market.

Expanding his performance analysis a bit more, Bessembinder found that the 1,000 top-performing stocks, less than four percent of the total, accounted for all of the public stock market’s wealth creation. That means the remaining 96 percent of stocks merely matched the return of one-month U.S. Treasury bills, 58 percent of all stocks underperformed one-month T-bills, and most lost money over their lifetimes.3

Another study, covering the period 1983-2006 utilizing the Russell 3000 Index, achieved similar and consistent results.

In later research (here and here), Bessembinder looked at the top 100 companies based on shareholder wealth creation by decade beginning in 1950. He discovered that even the greatest companies suffered big drawdowns (32.5%, on average), during their decade of peak performance. Even worse, during the decade before the peak decade, shareholders suffered an average maximum drawdown of 51.6 percent.

The duration of these drawdowns varied widely, lasting anywhere from a month to three years during the peak decade and up to eight years during the decade before that. Complete data below.

The implications of this research are astounding. As we know, there is a large equity risk premium to be had investing in stocks. However, the overwhelming majority of individual stocks have negative risk premiums, which explains why diversification is so important. Moreover, Bessembinder’s results help explain why active investment strategies, which tend to be poorly diversified, so often lead to poor performance. Therefore, long-term investors will almost certainly have to endure multiple, often painfully long periods of underperformance and deep drawdowns to reap great rewards.

Perhaps most significantly, these findings demonstrate that you are highly, highly unlikely to discover “the next Amazon.” Other research confirms that successful stock-picking is highly unusual, even among alleged experts. Finding “the next Amazon” in advance is almost insanely difficult – perhaps impossible4 – without some serious luck.

But let’s suppose for a moment that you could.

If you had invested $10,000 in Amazon at its IPO price ($18) in 1997, you would have purchased 555 shares, not counting commission expenses or fractional shares. Considering Amazon's four stock splits, those 555 shares would now be 133,200 shares. At yesterday’s $88.45 closing price, down almost 50 percent YTD, over those 25 years and change, your $10,000 would have become almost $12 million, an almost inconceivable return (over 27.5%), despite the enormous losses so far in 2022.5

Who wouldn’t love that! However, consider the drawdowns you would have had to endure to get those returns. How many of us could truly stomach a 91 percent drawdown and multiple 50 percenters, as AMZN shareholders have had to endure?

I’ll take the under.

Source: The New Yorker

My friend, Wes Gray, has shown that even God would get fired if He were managing other people’s money. Wes created a hypothetical stock portfolio constructed with perfect foresight, invested entirely in the top decile of stocks based on their performance over the upcoming five years. In other words, God made sure to own the stocks He knew would perform best over the next five years. After five years, Wes rebalanced the portfolio to invest only in the top performers for the next five years, and so on. He ran this exercise from 1927 to 2016 covering the 500 largest publicly listed stocks in the United States.

Over that 90-year investment horizon, God’s portfolio compounded at almost 30 percent per year. That’s even better than Amazon!

Such an investment – were it possible – would have turned just $1 into almost $12 billion! By way of comparison, the S&P 500 returned, on average, almost 10 percent annually during that time (which is very good, obviously), meaning a $1 investment would have grown to about $5,000.

Here's the most important thing.

While the theoretical value created by God’s portfolio is obviously staggering, the drawdown profile is even more astonishing. Instead of protecting against large reversals, God’s portfolio endured the pain of drawdowns that exceeded 20 percent ten separate times, including a 76 percent drawdown that lasted for three years.

As Wes points out, given that drawdown profile, if God were a money manager, most of us would fire Him.

Even the best possible investments suffer huge (and thus terrifying) drawdowns. If we bought “the next Amazon,” we’d suffer a lot of pain. If we had perfect foresight and bought stocks accordingly, we’d still suffer a lot of pain.

Pain is part of the process.6

With (always 20:20) hindsight, this reality may not seem like too big a deal. We’re focusing on and cannot ignore today’s value. However, in the moment, our loss aversion and our impulsive performance-chasing militate strongly against our being able to hold on when investments inevitably suffer losses. Especially big losses.

The sad fact is that when market volatility seems oppressive, many investors bail. They say they simply cannot stomach the losses. That’s why the “behavior gap” between investment returns and investor returns is so significant and so potentially damaging. Many – probably most – investors who cash out when negative volatility rears its ugly head will see their chances of investment and retirement success decrease significantly.

Stocks don’t generally offer Amazon-level returns, of course. But the returns they do provide are very, very good indeed.

Negative volatility hurts. Oftimes, it hurts a lot. However, such volatility is the necessary price to be paid for the much higher returns provided by stocks as compared with other investment choices. Investors would be wise willingly to pay-up. And hold on for the ride.

Totally Worth It

I love, love, love the following.

Feel free to contact me via rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or on Twitter (@rpseawright) and let me know what you like, what you don’t like, what you’d like to see changed, and what you’d add. Praise, condemnation, and feedback are always welcome.

Of course, the easiest way to share TBL is simply to forward it to a few dozen of your closest friends.

Please send me your nominations for this space to rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or via Twitter (@rpseawright).

You may hit some paywalls below; most can be overcome here.

This is the best thing I read this week (it combines magic, music, mystery, and math); this is the best thing I saw. The saddest. The sweetest. The smartest. The silliest. The stupidest. The wildest. The loveliest. The coolest. The nicest. The most important. The most absurd. The most astonishing. The most alarming. The most disappointing. The most nostalgic. The most powerful. The most perceptive. The most promising. The most commonsensical. The least surprising. The best headline. Penalties. “Sacrifice her.” Iguana outage. Tinder swindler. The critical question. “People think I’m stupid.” The impact of crime is underrated. Factcheck: True. Spectacularly and hilariously bad. RIP, Grant Wahl.

The TBL Spotify playlist, made up of the songs featured here, now includes more than 240 songs and about 17 hours of great music. The TBL Christmas playlist is here. Whichever one you listen to, I urge you to listen in, sing along, and turn up the volume.

Benediction

This week’s benediction features J.S. Bach. It’s gorgeous.

To those of us prone to wander, to those who are broken, to those who flee and fight in fear – which is every last lost one of us – there is One who offers grace and hope. And may love have the last word. Now and forever.

Amen.

Thanks for reading.

Issue 133 (December 16, 2022)

Investors with shorter-term time horizons and cash needs should, of course, plan carefully for the very real potential of near-to-intermediate-term drawdowns.

For me, the “one that got away” was one I have no excuse for missing. The 30-year U. S. Treasury bond reached its all-time high yield in October of 1981 at 15.21 percent. Even as a young lawyer without much money, I should have bought long-dated U.S. government-guaranteed paper at 15 percent. Even better, I should have paid a bit more than $14 and bought zero-coupon UST STRIPs that would have paid par ($100) 30-years later in 2011. That’s a trade in the same league as the Yankees getting Babe Ruth from the Red Sox for $125,000 in 1920 (about $1.2 million in today’s dollars). The Yankees gave the Babe an improved contract so that, in 1920, he earned $20,000 (about $300,000 in today’s dollars). Note that Aaron Judge recently signed with the Bronx Bombers for $40 million per season over nine years.

Foreign stock returns are even more extreme.

On Wednesday, Fed Chair Jerome Powell made this general point in another context: “I just don’t think anyone knows whether we’re going to have a recession or not. And if we do, whether it’s going to be a deep one or not ... it’s not knowable.” If you’re wondering, the reason these sorts of multi-variable problems are unsolvable is physics’ three-body problem.

Over that same 25-year (and change) period, the S&P 500 returned “only” 8.2 percent annually, including dividends – still pretty great (a $10,000 investment would have grown to over $80,000).

As Wes said: “You can lead an investor to a winning strategy, but you can’t make them stick with it when the going gets tough. Unfortunately, success comes at a steep price. You need to be willing to sit through periods of downright dreadful performance. No risk, no reward. It really is that simple.”