How You Doin'?

Benchmarking, in essence, is asking, "How you doin'?"

Friends was a television ratings juggernaut for ten seasons from 1994-2004. My wife and I were busy rearing our children during that time and missed it entirely. We caught up during the Covid pandemic and got a lot of laughs out the series.

In the middle of the fourth season, Joey’s signature phrase appears for the first time. Of course, it’s a pickup line. As Joey described it, he simply looks a woman up and down – lasciviously – and says, “Hey, how you doin’?” Rachel and Phoebe are skeptical, but he demonstrates it on Phoebe, and she can’t help but blush and giggle. Over 236 episodes, he used it only 19 times, nine successfully.

This edition of TBL is a riff on benchmarking, which is essentially a mechanism to ask the same question, if less lasciviously.

If you like The Better Letter, please subscribe, share it, and forward it widely.

If you’re new here, check out these TBL “greatest hits” below.

NOTE: Some email services may truncate TBL. If so, or if you’d prefer, you can read it all here. If it is clipped, you can also click on “View entire message” and you’ll be able to view the entire post in your email app.

Thanks for reading.

How You Doin’?

Who’s the best long-term investor of all-time?

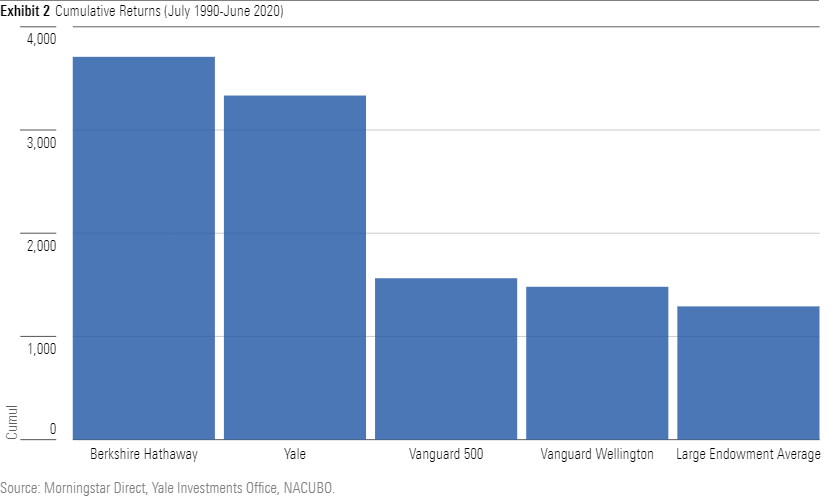

The late Jim Simons of Renaissance Technologies probably achieved the best returns (said to be nearly 40 percent annually, net of fees, over four decades), but his fund was closed to outside money for a very long time. Peter Lynch ran the famed Magellan Fund from 1977 to 1990. During that stretch, he generated astounding returns (29.2 percent per annum), but he got out while the getting was good. There are other plausible answers. However, for my money, Warren Buffett is the best long-term investor of all-time. The late David Swensen is a close second.

Buffett is justly famous while Swensen is much less so, at least to the general public.

In 1974, Yale economist and Nobel laureate James Tobin wrote that “the trustees of endowed institutions are the guardians of the future against the claims of the present. Their task in managing the endowment is to preserve equity among generations.” From that point, Yale’s endowment investment policy became focused on intergenerational equity. His protégé, David Swensen, would embody that idea and put meat on its bones.

Swensen was the chief investment officer at Yale University from 1985 until his death in 2021. He pioneered a portfolio management strategy that became known as the “Yale Model.” Over those 36 years, Swensen reimagined endowment investing such that the traditional 60/40 portfolio that had prevailed before him transitioned into a portfolio dominated by exposure to private markets. The revolution he initiated, due to the performance he achieved, spread to other endowments (many of whose leaders he trained) and foundations, then to sovereign-wealth and pension funds, to private offices and money managers for the super-rich, and even to retail investors.

The Yale Model uses broad diversification and the equity risk premium to its advantage, allocating much less to traditional U.S. equities, almost nothing to bonds, and much more to alternative investments like private equity, venture capital, leveraged buyouts, hedge funds, and real estate. Its intergenerational time horizon (essentially “forever”) allows Yale to gain excess returns by using illiquid assets in ways those without that opportunity could not.

Because Yale had access to the best managers in often esoteric markets,1 Swensen could dramatically lower Yale’s exposure to public securities. With private market data limited, Swensen (correctly) believed he and his team were good enough to create an edge and profit there, despite the higher risk.2 Yale’s intergenerational time horizon meant that Swensen could take on illiquidity for better returns.

He summarized here.

“Three basic investment principles inform asset-allocation decisions in well-constructed portfolios. First, long-term investors build portfolios with a pronounced equity bias. Second, careful investors fashion portfolios with substantial diversification. Third, sensible investors create portfolios with concern for tax considerations. The principles of equity orientation, diversification, and tax sensitivity find support both in common sense and academic theory.”

In Swensen’s 36 years at the helm of the Yale Endowment, it grew from $1.3 billion to over $40 billion, despite billions in outgoing distributions to support the university, with a whopping 13.7 percent compound annual gain. Despite many imitators, few (if any) have achieved comparable results. Indeed, few have outperformed the staid old 60/40. Interestingly, and according to Yale’s own calculations, only 40 percent of its alpha is attributable to asset allocation. The remaining 60 percent is attributable to superior managers.

Swensen himself advised: those without Yale’s access and expertise shouldn’t try to emulate its investment strategies. In other words, the first people to the buffet table get most of the tasty stuff. Everybody else would be better off eating elsewhere. Swensen may as well have said, “Don’t try this at home.” Indeed, he pretty much did.3

It should be far beyond obvious that Swensen achieved spectacular investment results for Yale. Far less obvious is how that success should be benchmarked (see here). One could designate a benchmark index for each of Yale’s asset classes, but that is much easier said than done. Yale compares itself to the median 10-year return for college and university endowments and a traditional 70/30 fund, beating each handily (so far, anyway). Because Yale’s portfolio essentially replicates a 95 percent equity fund with some (limited) liquidity for distributions, one could use a broad-based equity index.

Brief Aside (this could be a footnote, but I don’t want you to miss it)

Because almost nobody outperforms an appropriate benchmark, it’s easy to miss the sorts of returns that would be possible if anybody were truly good at picking stocks. In 2024, the S&P 500 did great (+25.02 percent, including dividends), but Palantir Technologies did a lot better, returning 340 percent (despite a very bad week, it’s still up about 12 percent so far in 2025). Had you rotated into the best S&P 500 stock each month – SMCI in January (+89 percent); SMCI again in February (+60 percent); VST in March (+28 percent); and so on through AVGO in December (+43 percent) – your portfolio value would have grown roughly +7,073 percent for the year. Had you rotated into the best S&P stock each week, your portfolio would have returned over 10,000 percent. Had you owned the best performing S&P 500 stock each day (Moderna on January 2, +12.6 percent; Southwest Airlines on January 5 +4.7 percent…), your return for the year would have been astronomical; your portfolio value would have grown to more than the current value of the whole market. For perspective, even a “mere” 2 percent daily gain (over its history, I could not find a day in which every S&P 500 stock declined in value), compounded over 252 trading days, would have returned about 1.5×10^5 percent!

We return you, now, to your regularly scheduled program.

However, as my friend Jason Zweig says, investing is less about beating others at their game than mastering yourself in your own game. Swensen’s annual reports all took care to describe what Yale was able to do because of the returns the endowment earned. That’s probably the best way to answer the “How you doin’” question. For individual investors, it means evaluating investment performance based upon how well one’s goals are reached.

As I wrote here, one might look at things even more broadly.

“Like compound interest, success is sequential. It takes time for good choices to add up before exploding exponentially. All the best things in our lives provide benefits that compound. Our financial investments do that, and so do our personal and family investments. Generosity and service compound. So do healthy living and education. Love is the most powerful compounder of all.

“Focus your purposes there.

“We don’t completely control our destinies or our legacies. But if we invest well – financially and otherwise – our legacies can be profound….

“As investments need to be benchmarked, our lives need it too. No matter what we say, we show what we love by how we invest our time, our talents, and our treasure. We reveal our whys with our love. Our purposes provide benchmarks.”

So, how you doin’?

Totally Worth It

In one of the more predictable news developments ever, the Museum of Failure, slated to open in a few weeks in (of course) San Francisco, is embroiled in a property dispute that will probably ensure its, um, failure … before it even opens.

Feel free to contact me via rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or on Twitter (@rpseawright) and let me know what you like, what you don’t like, what you’d like to see changed, and what you’d add. Praise, condemnation, and feedback are always welcome.

Of course, the easiest way to share TBL is simply to forward it to a few dozen of your closest friends.

You may hit some paywalls below; some can be overcome here.

This is the best thing I’ve read recently. The funniest. Also very funny. The creepiest. The most incredible. The most interesting. The most terrifying. Also terrifying. The best sign. Temper, temper. Good news. RIP, Roberta Flack. Fontastic.

Actor Gene Hackman died Wednesday at the age of 95. He appeared in dozens of memorable films, including Bonnie and Clyde, The French Connection, Mississippi Burning, Hoosiers, The Conversation, Unforgiven, and many more. He won two Academy Awards and became known as a veritable Hollywood everyman over the course of his long career. He and long-time friend Dustin Hoffman talk about budgeting when they were starting out and broke here (my mother used envelopes of cash she carried around in her purse).

Please send me your nominations for this space to rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or via Twitter (@rpseawright).

Around half the world’s population live in places that held elections in 2024. Some 1.65 billion ballots were cast across more than 70 countries. But while the number of democratic elections in a single year has never been higher, 2024 also brought big challenges. According to the latest democracy index, global democracy is in worse shape than at any point in the nearly two-decade history of the index. If, as I do, you believe economies and markets perform better when there is more freedom, you might take a look at this (DISCLOSURE: I own it).

As I write this, the current yield on the benchmark 10-year U.S. Treasury note is 4.29 percent, down 51 basis points from its 4.80 percent high just before Inauguration Day. The new administration is succeeding so far in its goal to get bond yields lower, which seems to have replaced the S&P 500 as President Trump’s measure of success.

Benediction

Today’s benediction is a great Vince Gill song sung by Vince and Patty Loveless at the Grand Ole Opry. Note the wonderful addition of a third verse. As Vince says, quoting his grandmother, “If your eyes leak, your head won’t swell.”

We live on “a hurtling planet,” the poet Rod Jellema informed us, “swung from a thread of light and saved by nothing but grace.” To those of us prone to wander, to those who are broken, to those who flee and fight in fear – which is every last lost one of us – there is a faith that offers love and hope. And may grace have the last word. Now and forever. Amen.

As always, thanks for reading.

Issue 183 (February 28, 2025)

The gap in performance between top- and bottom-quartile PE funds is much larger than in public markets – perhaps 15 percentage points or more. Indeed, about one-fifth of PE investments do not even return investor principal.

Private equity’s “beta” (risk relative to the public markets) is generally 20-30 percent higher than that of equities. Moreover, the premium for illiquidity is, as a rule of thumb, about three percentage points a year.

Many retail advisors and investors tried to emulate the Yale Model. Essentially all of them regret it. Many institutional investors also tried to emulate the Yale Model. The realities of the space prevent it, but the overwhelming majority of them should regret it.