Confirmation Bias Writ Large

“I beseech you, in the bowels of Christ, think it possible that you may be mistaken.”

Happy Thanksgiving!

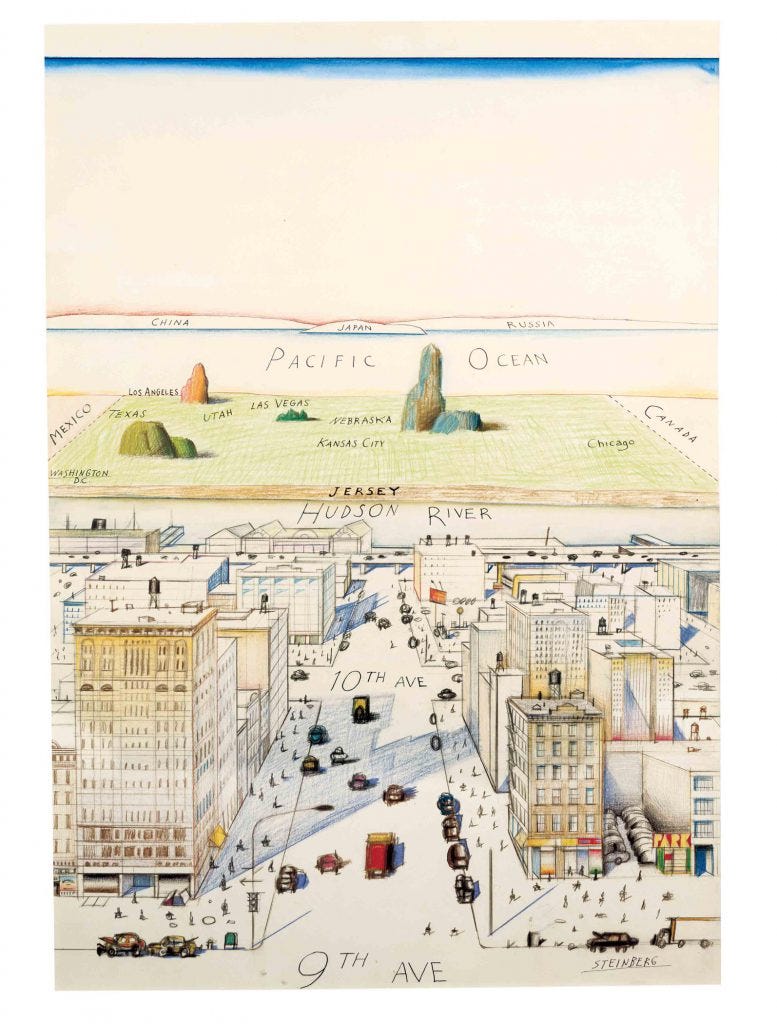

What has rivers but no water, forests but no trees, and cities but no buildings? A map. This edition of TBL examines Alfred Korzybski’s famous metaphor: the map is not the territory. If you like The Better Letter, please subscribe, share it, and forward it widely.

NOTE TO SUBSCRIBERS: Some email services may truncate TBL. If so, or if you’d prefer, you can read it all online here. If it is clipped, you can also click on “View entire message” and you’ll be able to view the entire missive in your email app.

Thanks for reading.

Confirmation Bias Writ Large

When I picture what the world looks like, I think of the Mercator projection.

It was the map of my grade school textbooks and the classroom “pull-downs” of my childhood. It was created in 1569 by geographer and cartographer Geert de Kremer, better known as Mercator, and became the standard map projection for navigation because it allowed sailors to set courses using only the map, their observations, and a compass.

Other maps before and since have been better at showing us the whole earth, but the Mercator projection was the first that provided us a way of exploring it by providing a simple and reliable means of navigating across an ocean. If you want to sail from Spain to the West Indies, for example, simply draw a line between those two points on the Mercator map. Doing so provides the exact compass direction to sail to reach the desired destination.

However, as Gauss conclusively demonstrated, the surface of a sphere cannot be represented as a plane without distortion. Accordingly, cartographers – from long before Gauss – recognized that such representations are imperfect and involve compromises in shape, distance, land area, and direction.

As its necessary side effect, the Mercator projection inflates the size of objects away from the equator. This inflation is very small near the equator but accelerates with increasing latitude to become infinite at the poles. For example, Greenland looks to be about the same size as Africa even though it is only about 1/14 its size – about the size of the Congo. Despite what the map shows, Canada would comfortably fit inside Africa and Africa is more than twice the size of Antarctica.1

There is thus inherent tension between the accuracy and usability of a map. This tension, particularly in the context of modeling, is known as Bonini’s paradox, and has various iterations, such as a poetic construct by Paul Valéry: “Ce qui est simple est faux, ce qui est compliqué est inutilisable” (“Everything simple is false. Everything which is complex is unusable”). Or, as Alan Watts argued, the menu is not the meal.

Today, the Mercator projection is still found in marine charts, occasional world maps, and Web mapping services, while commercial atlases have largely abandoned it. Wall maps of the world now exist in many alternative projections, each with its own weaknesses and compromises.

The Mercator projection offers a handy and surprisingly literal illustration of Alfred Korzybski’s famous metaphor: the map is not the territory. Korzybski emphasized that symbols (“maps”) are not the things symbolized (the “territory”).2

In the financial world, this metaphor is frequently applied to models. As George Box famously wrote, “all models are wrong, but some are useful.”3 It is imperative to bear in mind that models are – of necessity – simplifications and approximations of the realities they represent. Shane Parrish has an excellent analysis of the problems in this area here; a powerful example of the over-reliance on models leading to catastrophe is examined here.

The problem is much broader than that, however. It applies to every description, every representation, and every belief. Thus, as Korzybski emphasized, “[t]hose who rule the symbols, rule us.”

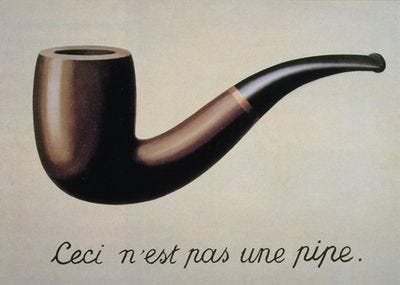

You may recall The Treachery of Images, by surrealist artist Rene Magritte, from a college class in philosophy.

The text translates to “This is not a pipe” and, of course, it isn’t. We can’t stuff this (digital) image with tobacco and smoke it. It is merely a representation of a real object. As Thoreau wrote, “It’s not what you look at that matters, it’s what you see.”

Neil Gaiman restates the problem in reference to storytelling in his Fragile Things.

“One describes a tale best by telling the tale. You see? The way one describes a story, to oneself or the world, is by telling the story. It is a balancing act and it is a dream. The more accurate the map, the more it resembles the territory. The most accurate map possible would be the territory, and thus would be perfectly accurate and perfectly useless. The tale is the map that is the territory.”

Korzybski’s metaphor undergirds the narrative fallacy (which I have written about before) and highlights the differences between belief and reality. We weave our observations into a narrative to aid understanding. Reality exists independent of us yet we can construct models of this “territory” through the use of our senses. However, adding to, subtracting from, or simply changing one’s map doesn’t materially alter the territory.

Theory need not correspond to reality, mental models are necessarily flawed, and beliefs may be false. Reality is either one way or another; beliefs are probabilistic.

Even so, that which we truly believe feels like reality – the way the world is – from inside our heads. Yet other peoples’ mileage can and routinely does vary. They aren’t disagreeing with you because they’re obstinate, they’re disagreeing because they see the world differently. We – each of us – tend to see ourselves as the protagonists in our own story, with everyone else supporting players, forgetting that everybody else thinks they’re the star, too. In real life, different elements of reality have different meanings and different levels of importance to different people.

Because of this problem, most of what passes for discourse about what really matters in today’s world rarely gets beyond the point of lecturing misbehaving children who are refusing to acknowledge obvious truth. Note, too, that being wrong feels exactly like being right, unless and until you can (or are willing to) perform some sort of experimental check on your belief. And, it shouldn’t have to be said, but needs to be, there are not different truths, whatever the post-moderns might allege.

Appreciating that our beliefs about reality need not be true can help us to recognize the primacy of reality, rather than our beliefs about it. Accordingly, we can either stop arguing with reality and accept it or, at least, become curious about it and check our work. Epistemic humility for the win!

Oliver Cromwell wrote to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland on August 3, 1650, shortly before the Battle of Dunbar, and offered a simple but powerful admonition.

“I beseech you, in the bowels of Christ, think it possible that you may be mistaken.”

Error leaves no cognitive trace. Thus – always, always, always – bias blindness rears its ugly head. As Charlie Munger famously said, “If you can get good at destroying your own wrong ideas, that is a great gift.”

The scientific approach necessarily recognizes the map/territory distinction by requiring testing (sadly, too often honored only in the breach, as the ongoing replication crisis and censorship problem demonstrate). Knowledge, as it was espoused in medieval universities and monasteries, was dominated by the ancients, the likes of Ptolemy, Galen, and Aristotle. It was widely believed that all the most important knowledge was already known. Thus, learning was predominantly a backward-facing pursuit, about returning to ancient first principles (the map), not pushing into the unknown (the territory).

Aristotle, brilliant and important as he was, posited, for example, that heavy objects fall faster than lighter objects and that males and females have different numbers of teeth, based upon some careful – though flawed – reasoning. But it never seemed to have occurred to him that he ought to check.

The scientific revolution changed that outlook. Its primary discovery was ignorance. Then, as now, no matter what the map said or suggested, there was much still to be known. For example, over 95 percent of the universe’s matter and energy are unobservable; modern calculations say dark matter comprises about 27 percent of the universe, yet we don’t yet even know what it is. Historian of religion Jonathan Z. Smith concluded his book, Map is Not Territory, with a thoughtful rejoinder.

“We need to reflect on and play with the necessary incongruity of our maps before we set out on a voyage of discovery to chart the worlds of other men. For the dictum of Alfred Korzybski is inescapable: ‘Map is not territory’ – but maps are all we possess.”

It’s tempting to compose a paean to science and, more broadly, critical thinking at this point. However, I hasten to add that science and critical thinking are practiced by humans, who are altogether, er, human, and thus are consistently and constantly prone to wander.

Watch the following classic bit of “sherlocking,” wherein Holmes creates an entire explanatory narrative from a few careful observations (which of course works out a whole lot better on television than in real life).

Despite the neat and tidy script, Sherlock fails to “exhaust the hypothesis space.” He is far too certain of his ability to marshal all the possibilities. Each of us can come up with several alternative scenarios that fit Sherlock’s facts with just a bit of thought. The number of possible hypotheses will almost surely exceed the imagination of one inherently limited thinker, even one as gifted as Sherlock Holmes. Or Aristotle. The “highly improbable” is indeed possible, as Sherlock proclaims, but less likely than an unconsidered hypothesis. Each of us is limited by our humanity: a lack of knowledge, a lack of imagination, and our biases.

In essence, the map/territory problem is confirmation bias writ large, whereby we see what we want to see, accept those desires as truth, and act accordingly. As Annie Duke says, we’re built for false positives.

We quite naturally try to jam facts – real and imagined – into our preconceived notions and commitments or simply miscomprehend reality such that we accept a view, no matter how implausible, that sees a different set of alleged facts, “facts” that are used to support the maps we have already created. So, when we grab a glass of what we think is apple juice, take a sip, and find out it’s really ginger ale, we react with disgust, even when we love ginger ale. Moreover, we all too frequently remain willfully ignorant about facts that are inconvenient (more here and here).

On our better days, we might grudgingly concede that we hold views that are wrong. The problem is with providing current examples. We’re lousy at seeking and finding disconfirming information and, thus, at eliminating bad ideas. We keep mistaking the map for the territory.

Totally Worth It

As I write this, it was exactly 60 years ago (November 22, 1963) that JFK was assassinated. I heard about it from my elementary school principal, over the loudspeaker in my second grade classroom. Aldous Huxley died that same day. And so did C.S. Lewis, who is still speaking to us today. For example, note the following (from The Screwtape Letters, “written” by a senior demon to a fledgling tempter).4

“Courage is not simply one of the virtues but the form of every virtue at the testing point, which means at the point of highest reality.”

Feel free to contact me via rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or on Twitter (@rpseawright) and let me know what you like, what you don’t like, what you’d like to see changed, and what you’d add. Praise, condemnation, and feedback are always welcome.

Of course, the easiest way to share TBL is simply to forward it to a few dozen of your closest friends.

The following is the best thing I saw over the past week. It makes subtle and judicious use of “In My Life,” by The Beatles. Your viewing experience will be enhanced if you know the lyrics.

There are places I'll remember All my life though some have changed Some forever not for better Some have gone and some remain All these places had their moments With lovers and friends I still can recall Some are dead and some are livingIn my life I've loved them all But of all these friends and lovers There is no one compares with you And these memories lose their meaning When I think of love as something new Though I know I'll never lose affection For people and things that went before I know I'll often stop and think about them In my life I love you more Though I know I'll never lose affection For people and things that went before I know I'll often stop and think about them In my life I love you more In my life I love you more

You may hit some paywalls herein; many can be overcome here.

This is the best thing I read over the last week. The funniest. The coolest. The most absurd. The most incredible (huge losses on options trading are not even at the top of the list of incredible things). More Dave Ramsey. Why all the $50s? Tipping. The jungle gym is 100. Quality. Simplify. Tragic that it needs to be said. (Gridiron) football is doomed. Tolstoy’s apologetic.

Please send me your nominations for this space to rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or via Twitter (@rpseawright).

10 non-fiction books that changed me, without comment and in no particular order (h/t Daniel Crosby): Ubiquity; The Wizard and the Prophet; Expert Political Judgment; The Master and his Emissary; The Invention of Science; When Prophecy Fails; The Structure of Scientific Revolutions; Fooled by Randomness/The Black Swan; Christianity’s Dangerous Idea; and Reverence. What book(s) changed you?

The TBL Spotify playlist, made up of the songs featured here, now includes over 260 songs and about 19 hours of great music. I urge you to listen in, sing along, and turn up the volume. The TBL Christmas playlist is here.

My ongoing thread/music and meaning project: #SongsThatMove

Benediction

Everybody reading TBL has a great deal for which to be thankful. As my friend Morgan Housel explained: “reading this means you belong to the only species out of 8.7 million on this planet that can read. And our planet is the only one out of 100 billion in our galaxy that we know has life.”

Or, as Don Boudreaux wondered, it’s not obvious that you’d be better off if you were a billionaire 100 years ago rather than remaining solidly middle-class in America today.

We could have been born in the 7th Century. We could have been born in North Korea. Nick Heil explained it pretty well: “you never really know how lucky you are until your luck runs out.”

Thanksgiving starts with thanks for mere survival, Just to have made it through another year With everyone still breathing. But we share So much beyond the outer roads we travel; Our interweavings on a deeper level, The modes of life embodied souls can share, The unguessed blessings of our being here, The warp and weft that no one can unravel. So I give thanks for our deep coinherence Inwoven in the web of God's own grace, Pulling us through the grave and gate of death. I thank him for the truth behind appearance, I thank him for his light in every face, I thank him for you all, with every breath. ~ Malcolm Guite (you can hear the author read it here)

This week’s benediction is a wonderful Thanksgiving song by Ben Rector, covered by the Petersens.

We live on “a hurtling planet,” the poet Rod Jellema informed us, “swung from a thread of light and saved by nothing but grace.” As Charles Spurgeon preached, “So long as we are receivers of mercy, we must be givers of thanks.”

To those of us prone to wander, to those who are broken, to those who flee and fight in fear – which is every last lost one of us – there is a faith that offers grace and hope. And may love have the last word. Now and forever. Amen.

As always, thanks for reading.

Issue 159 (November 24, 2023)

A modern critique of the Mercator projection, not directly relevant to this discussion, and surely overstated, is that it perpetuated European imperialist attitudes of domination toward countries near the equator.

It’s not a new idea, of course: “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy (Hamlet Act 1, scene 5).”

Statistician J. Michael Steele argues that “wrong” only comes into play if the model does not correctly answer the question that it claims to answer.

There is a phony Screwtape quote making the rounds about being “completely fixated on politics.”

Glad I found your blog... thinking about how we think is the only way I see for a civil humanity

Just getting to this. As a financial markets trader for 43 years I strongly agree about models and confirmation bias.

Loved Screwtape and Fooled by Randomness. I’d also highly recommend Kahneman’s Thinking Fast and Slow and Cialdini’s Persuasion.

Thank you for your efforts and sharing.