On Tuesday, the Doomsday Clock was moved to 90 seconds to midnight, the closest it has ever been to Armageddon. During its 76-year history, it has never been further from presumed annihilation than just 17 minutes, in 1991.

For a surprising number of people, including the atomic scientists who run the Doomsday Clock, the apocalypse is always nigh. The reasons, descriptions, and timetables may change, but there will never be a shortage of doomsday prophets, who always live in the shadow of death. One particular doomsday prophet, also a scientist, is the subject of this week’s TBL.

If you like The Better Letter, please subscribe, share it, and forward it widely.

NOTE: Some email services will likely truncate TBL. If so, or if you’d prefer, you can read it all here. If it is clipped, you can also click on “View entire message” and you’ll be able to view the entire post in your email app.

Thanks for reading.

Cassandra's Curse ... in reverse

Stanford University biologist Paul Ehrlich took to 60 Minutes on New Year’s evening to declare, not for the first time: “[W]e’ve had it, …the next few decades will be the end of the kind of civilization we’re used to.” In other words, “Humanity is not sustainable.”

It’s a road we’ve been down before. As ever, Ehrlich is a prophet proclaiming the good news of impending death.

From time immemorial, people have sought to play God, even to be God. We’re terrible at it. As the late great polymath Freeman Dyson explained, history is replete with those “who make confident predictions about the future and end up believing their predictions.” Ehrlich should be Exhibit A.

One way or another, he’s certain the world is about to end. Essentially all the time. He’s been wrong for 55 years and more, but he’s never in doubt.

When 1968 dawned, the world was a dark place. The Vietnam War was raging. The Middle East was a powder keg. The Cultural Revolution and its purges were in full flower throughout China. Soviet and other Warsaw Pact troops used 6,500 tanks and 800 aircraft to invade Czechoslovakia, crushing dissent there. It was the largest military operation in Europe since World War II. The Doomsday Clock read seven minutes to midnight.

When 1968 dawned, America was a dark place. The “generation gap” was wide. Nearly 17,000 American boys came home from Vietnam in body bags that year. Those who came home alive were too often treated horribly. American streets and campuses were raging, as protests over the war and civil rights headlined the news. It was the most prolific period of domestic terrorism in our history – over 300 bombings that year.

In April, Martin Luther King Jr. was shot dead at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee, leading to riots in major American cities, which lasted for days. Bobby Kennedy was assassinated in June, at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, shortly after he won the California Democratic Primary.

When 1968 dawned, Paul Ehrlich was a little-known entomologist who was about to (pardon the pun) blow-up. His quickly written, cheaply bound pulp propaganda piece, The Population Bomb, released in May, would sell over three million copies and turn Ehrlich into a celebrity, a MacArthur Fellow, a Crafoord Prize winner, and over 20 times Johnny Carson’s guest on The Tonight Show. The book would become one of the more influential of the 20th century.

The opening lines of the book’s Prologue state the case.

“The battle to feed all of humanity is over. In the 1970s the world will undergo famines – hundreds of millions of people are going to starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now. At this late date, nothing can prevent a substantial increase in the world death rate….”

“Population control, of course, is the only solution to population growth,” he proclaimed (emphasis in original). He promoted luxury taxes on diapers in America and forced sterilizations in India, adding: “Coercion? Perhaps, but coercion in a good cause.”

He discouraged marriage and argued that “[t]he FCC should see to it that large families are always treated in a negative light on television.” If that didn't work, he wanted imposed authoritarianism: The government should “legislate the size of the family” and “throw you in jail if you have too many” kids.

By 1980, “all important animal life in the sea will be extinct. Large areas of coastline will have to be evacuated because of the stench of dead fish” and “[s]ometime in the next 15 years, the end will come.”

Like any popular forecaster or good propagandist, he didn’t mince words or qualify his predictions. He was also wrong. About essentially everything.

Doomsday cults have existed throughout history and have proliferated in the modern world, extending to virtually every aspect of culture. It’s always a warning, but sometimes it’s an opportunity, too. Billionaires are now planning to escape by moving to Mars, for example.

Stories of humans trying to survive on a post-apocalyptic Earth are ubiquitous. Ehrlich’s specific approach, summarized in TPB, came to pervade popular culture, as in the over-populated, food-deprived, dystopian 2022 of the 1973 film, Soylent Green.

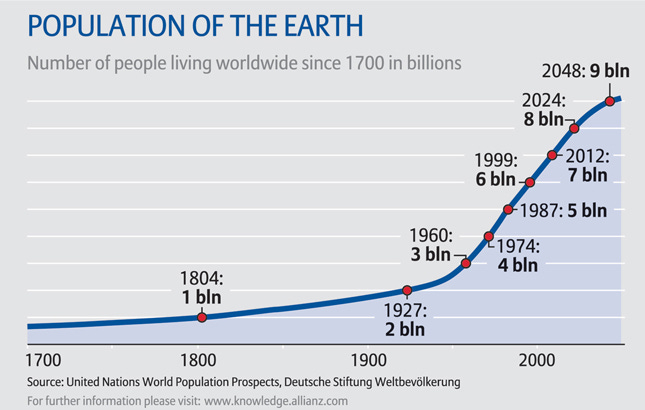

Like Malthus before him1 (in 1798), Ehrlich insisted that we were in a “race to oblivion” because, he thought, populations increase exponentially while food production doesn’t.

Nature seemed to hear Ehrlich’s jeremiad and do the opposite of what he prophesied. He was like Cassandra and her curse – fated to be always right but never heeded – only in reverse.

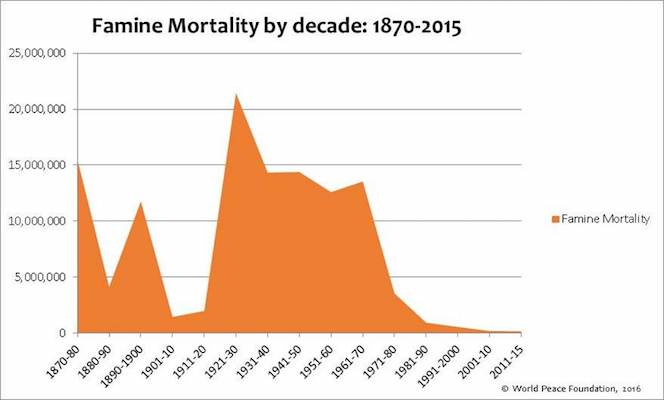

TPB’s publication date is significant because, ironically, 1968 was the peak of the global population growth rate, which has dropped consistently since. Moreover, the world’s death rate was 13.5 per 1,000 people that year; today, it is 7.7. World hunger was already trending downward. Wheat production in India increased by 45 percent over 1967.

In later editions of his book, Ehrlich extended the expected date of annihilation, but these new dead-by dates didn’t prove any more accurate. Instead, the things he harped on kept getting better.

The percentage of the world’s population that qualify as “undernourished” has fallen dramatically, from 33 percent when Ehrlich dropped his Bomb to less than 9 percent. The price of wheat has been cut roughly in half, when adjusted for inflation. The share of the population living in poverty has shrunk from 48 percent in 1970 to single digits.

Green Revolution

Unbeknownst to Ehrlich, the seeds of his errors were already sown (pardon the pun) when he began claiming the end was near. The “Green Revolution” was well underway. With selective breeding work begun in Mexico in the 1940s, biologist Norman Borlaug had created a dwarf variety of wheat that put most of its energy into edible kernels rather than long, inedible stems. The result: much more grain per acre. By 1956, Mexico’s wheat production had doubled, with much more advancement to come.

All told, Borlaug “saved more lives than any other person who ever lived.”

By the time Ehrlich wrote his Bomb in 1968, Borlaug had made further enhancements, creating a high-yielding, short-strawed, disease-resistant wheat, and population growth had begun to trend downward. Based upon Borlaug’s achievements, between 1961 and 2001, India nearly tripled its grain production. Pakistan became self-sufficient in wheat production. Similar work at the International Rice Research Institute in the Philippines dramatically improved the productivity of the grain that feeds nearly half the world.

The Population Bomb claimed, in 1968, it was “a fantasy” that India would “ever” feed itself. By 1974, India was self-sufficient in the production of all cereals.

From the 1960s through the 1990s, rice and wheat yields doubled. Even as the population continued to grow, grain prices fell, the number of people suffering food insecurity dropped, and the poverty rate was cut in half. When he won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970, just two years after Ehrlich’s screed, Borlaug’s citation read, “More than any other person of this age, he helped provide bread for a hungry world.”

Ehrlich claimed, quoting James Lovelock (here): “Prophets have been foretelling Armageddon since time began, he says. ‘But this is the real thing.’”

Narrator: “It wasn’t the real thing.”

Still, Ehrlich kept appearing on The Tonight Show to banter charmingly with Johnny Carson (with appropriate existential dread, of course) about the horrors that he was certain awaited us just around the corner.

When Ehrlich began his prophecies of imminent doom, world population was about three-and-a-half billion. Today, it’s nearly eight billion and, as of this writing, at least, we’re still here. Eating better. Living longer. Worldwide. Moreover, global population will likely plateau this century as country after country becomes wealthier and, with that wealth, birthrates plummet. Indeed, birthrates throughout the developed world are now below long-term replacement levels.

World hunger and poverty are dramatically reduced, too. Even in developing nations, the share of the population in absolute poverty has fallen to single digits.

Doubling Down

Ehrlich was almost entirely in error about everything. Few have done so well being so wrong. Furthermore, his claims encouraged human-rights abuses around the world, from forced sterilizations in India and elsewhere to forced abortions in huge numbers – perhaps 100 million, often in poor conditions contributing to infection, sterility, and even death – under China’s one-child policy.

Undeterred, Ehrlich kept making bold forecasts in the decades that followed.

“One general prediction can be made with confidence: the cost of feeding yourself and your family will continue to increase.”

Nope. When adjusted for inflation, food costs have trended consistently downward for decades.

Source: Chartbook of Real Commodity Prices, 1850-2020.

Never willing to leave well enough alone, Ehrlich has spent the past 55 years doubling down on his errors, seemingly at every opportunity.

“We must realize that unless we are extremely lucky, everybody will disappear in a cloud of blue steam in 20 years,” Ehrlich said in 1969.

In 1970, Ehrlich was specific with his predictions.

“Population will inevitably and completely outstrip whatever small increases in food supplies we make. The death rate will increase until at least 100–200 million people per year will be starving to death during the next ten years.”

For the inaugural Earth Day issue of The Progressive that year, he assured readers that between 1980 and 1989, some 4 billion people, including 65 million Americans, would perish in the “Great Die-Off.”

In Audubon, Ehrlich warned that Americans born since 1946 then had a life expectancy of only 49 years, and he predicted that if then-current patterns continued, this expectancy would reach 42 years by 1980.

Global life expectancy has risen from 55 to 72 years since The Population Bomb was published. U.S. life expectancy was 62 when Ehrlich, now 90, was born; although Covid reduced it a bit, it is now more than 77 years. Instead of famine and death, average food intake in calories has increased by more than 30 percent. We are so well fed globally that obesity is rising in Africa, the world’s poorest continent.

In 2018, Ehrlich called the shattering collapse of civilization a “near certainty.” He remains convinced that “perpetual growth is the creed of the cancer cell.”

As psychology has long understood, when our prophesies fail, we rarely self-correct. We double-down.

“When all else fails, there’s always delusion,” as Conan O’Brien likes to say.

The Bet

In 1970, Ehrlich said that “if I were a gambler, I would take even money that England will not exist in the year 2000.” That assertion eventually got the attention of the late Julian Simon, a University of Maryland economist, who saw such dystopian claims as “false bad news.”

Unlike other animals, Simon argued, humans can innovate their way out of scarcity by increasing the supply of natural resources, by developing substitutes, or through technological improvements. Accordingly, and for example, a tin can that weighed about three ounces in 1959 became an aluminum can that weighs less than half an ounce today. Simon liked to quote the 19th-century economist Henry George: “Both the jayhawk and the man eat chickens, but the more jayhawks, the fewer chickens, while the more men, the more chickens.” Thus, human ingenuity is “the ultimate resource” that can make all other resources more plentiful.

Ehrlich was outraged at and condescending toward Simon, adamant that population growth was outstripping the earth’s supplies of food, fresh water, and minerals. When he referred to “the ultimate resource,” he did it snidely: “the one thing we’ll never run out of is imbeciles.”

“To explain to one of them the inevitability of no growth in the material sector, or ... that commodities must become expensive, would be like attempting to explain odd-day-even-day gas distribution to a cranberry. … Julian Simon is like the guy who jumps off the Empire State Building and says how great things are going so far as he passes the 10th floor.”

He called Simon the leader of a “space-age cargo cult” of economists convinced that new resources would miraculously fall from the heavens, and a “fringe character.”

Karma’s a b*tch.

As he writes in his new memoir, Ehrlich was inspired by the resource scarcity highlighted in William Vogt’s Road to Survival (1948), wherein Vogt described the history of capitalism and its innovations as a “march of destruction.”

By 1975, Ehrlich was opposing economic progress generally: “Giving society cheap, abundant energy at this point would be the moral equivalent of giving an idiot child a machine gun.”

Simon knew better, so he challenged Ehrlich to a wager. The Bomb-thrower accepted, which was surprising because he saw Simon as an inferior, a mere “professor of business administration, specializing in mail-order marketing.” Ehrlich derisively announced that he would “accept Simon’s astonishing offer before other greedy people jump in.”

The 1980 bet was structured as a commodities futures contract. Simon agreed to sell Ehrlich $200 each worth of chromium, copper, nickel, tin, and tungsten – commodities chosen by Ehrlich – in 1990 at 1980 prices. The bet would pay off for Ehrlich if the metals became scarcer and thus costlier. On the settlement date, the prices of each individual commodity had declined over the decade on an inflation-adjusted basis (three dropped nominally) and the total price had declined by nearly 60 percent, from $1,000 to $423.93, despite population growth, meaning Simon won. By a lot. He would have won even without inflation adjustment (and there was a lot of inflation in the 80s).

Ehrlich mailed Simon a check for the balance: $576.07. Signed by his wife. Without a note.

“As soon as one predicted disaster doesn’t occur, the doomsayers skip to another,” Simon lamented.

“There’s nothing wrong with worrying about new problems – we need problems so we can come up with solutions that leave us better off than if they’d never come up in the first place. But why don’t the doomsayers see that, in the aggregate, things are getting better? Why do they always think we’re at a turning point – or at the end of the road?”

Indeed.

Notwithstanding the facts, Ehrlich continues to resist the obvious, insisting that “perhaps the most serious flaw in The Bomb was that it was much too optimistic about the future.” He continues to wait expectantly, almost hopefully, for an inevitable “collapse.” Indeed, “I do not think my language was too apocalyptic…. My language would be even more apocalyptic today.”

Earlier this month, 55 years later, he was still sure that “humanity is very busily sitting on a limb that we’re sawing off.” Scott Pelley of 60 Minutes acknowledged in a three-sentence aside that the Green Revolution disproved Ehrlich’s mass famine prediction in The Population Bomb, but returned directly to insisting the apocalypse is really coming this time. Ehrlich, yet again, offered good copy.

“Humanity is not sustainable. ... To maintain our lifestyle, yours and mine, basically, for the entire planet, you’d need five more Earths.”

Modern science has demystified reality – for good and for ill – fostering excessive certainty in its findings and hypotheses. Indeed, Ehrlich fits the stereotype of “Arrogant Scientist” perfectly. And he’s prickly when his errors are pointed out.

Doubting, questioning, or disagreeing with Ehrlich doesn’t make anyone a “science denier,” despite his many accolades. Indeed, claiming that dissenting points of view to the current orthodoxy – never mind a fringe-but-fashionable point of view – “denies” science is itself a kind of denial of the spirit of science, which, by definition and design, is supposed to be constantly retesting its assumptions.

In his brand new memoir, Life: A Journey through Science and Politics, published this week, Ehrlich emphasizes his fear that humanity has only about a one percent chance to avoid the collapse of civilization. He credits TPB for much-reduced birth rates. He still thinks massive population reduction and mandatory wealth redistribution are required to save the planet, now mostly from climate change and reduced biodiversity. He thinks the next 20 years will be “far worse.” We’re “on the brink” (as always) of major harvest shortfalls.

“Welcome back, my friends, to the show that never ends” (Emerson, Lake & Palmer).

Ehrlich still wants population “shrinkage,” (from eight billion down to about two billion), still proposes authoritarian solutions, still hates capitalism, and still thinks TPB is a great book. He stands behind its “basic pessimism.” The Green Revolution gets a single reference in the memoir – as a “short-term” explanation for why famine hasn’t been a bigger problem. Norman Borlaug and Julian Simon are not mentioned. He conceded no major errors other than being “too optimistic.”

Despite the clarity and specificity of both his predictions and his errors, Ehrlich compounded his mistakes by trying to deny that they were really errors. He sounded like a foolish market analyst insisting he was right but early when he asserted, “[o]ne of the things that people don’t understand is that timing to an ecologist is very, very different from timing to an average person.”

To be sure, I take climate change and other potential environmental calamities most seriously indeed, but the odds are strongly against our ever having everything (and especially future events) all figured out with great specificity, much less soon. Moreover, we should all recall the insidious incentives supporting bold predictions, most notably potential fame, funding, and influence, especially because there seems to be no accountability for being wrong.

We are loss averse because progress comes slowly, if at all, while disaster can happen overnight. Or faster. We notice when something explodes. We ignore that which recedes. The nature of cognition (we deal with threats first) and the nature of news (“if it bleeds, it leads”) intersect such that we are highly likely to think the world is worse than it is.

When predictions – and especially doomsday predictions – fail, it becomes easy to dismiss serious and very real problems.

As Stewart Brand, founding editor of the Whole Earth Catalog, wondered, “How many years do you have to not have the world end” to reach a conclusion that “maybe it didn’t end because that reason was wrong?”

Excellent question.

Totally Worth It

In Everything Is Going to Be Fine, San Francisco-based filmmaker Ryan Malloy goes in search of answers to how he ought to prepare for the worst and, more pressingly, how he should handle his doomsday anxieties in the meantime. Embarking on a journey that includes an interview with Ian Morris, an archaeologist and professor of Classics at Stanford University, sessions with a therapist, and time spent with “preppers,” Malloy’s approach is fretful yet lighthearted, ultimately landing on a note of optimism. Shot in 2011, the ideas the film explores are as relevant as ever, lending credence to the idea that widespread pessimism about humanity’s trajectory is a truly timeless feeling. And they fit beautifully with this week’s TBL.

Feel free to contact me via rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or on Twitter (@rpseawright) and let me know what you like, what you don’t like, what you’d like to see changed, and what you’d add. Praise, condemnation, and feedback are always welcome.

Of course, the easiest way to share TBL is simply to forward it to a few dozen of your closest friends.

You may hit some paywalls below; most can be overcome here.

This is best thing I read this week. The worst. The silliest. The stupidest. The scariest. The saddest. The smartest. The coolest. The loveliest. The most remarkable. The most astonishing. The most absurd. The most ridiculous. The most insane. The most incredible. The most interesting. The most real. The most pitiful. The most evenhanded. The most disconcerting. The most significant. The least surprising. The best question. The best news. The best interview. The best story. Completely obvious. Rule 11. Evil. Nobody should be surprised that dictatorships fudge. Very important. The power of technology. Reversible. Uh-oh. Oh my. Holy cow. Boy, I hope this is true. Unequivocally true. Good grief.

Please send me your nominations for this space to rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or via Twitter (@rpseawright).

The TBL Spotify playlist, made up of the songs featured here, now includes nearly 250 songs and about 17 hours of great music. I urge you to listen in, sing along, and turn up the volume.

Morissette is the best pop singer on the planet. In any language (translation from Tagalog to English here).

Benediction

Now unto Him who is able to keep you from falling, and to present you faultless before the presence of His glory with exceeding joy, to the only wise God our Savior, be glory and majesty, dominion and power, both now and forever.

Amen.

Thanks for reading.

Issue 139 (January 27, 2022)

Economics was first called “the dismal science” because of Malthus’s predictions of mass starvation which, we now know, were spurious.

I can predict with absolute certainty that I won't always share your viewpoint on every subject;) But on this one I do so passionately.