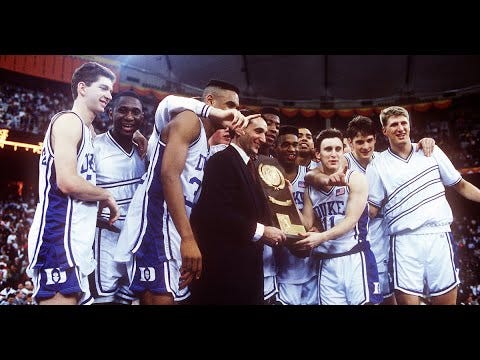

I love March Madness1. All of it. Upsets. Buzzer-beaters (I was in the stands for this one, in 1990).

One Shining Moment.

Controversy (innocent and not-so-innocent). Even the hype. Oh, and brackets, I love me some brackets, the subject of this edition of TBL.

If you like The Better Letter, please subscribe, share it, and forward it widely.

If you’re new here, check out these TBL “greatest hits” below.

NOTE: Some email services may truncate TBL. If so, or if you’d prefer, you can read it all here. If it is clipped, you can also click on “View entire message” and you’ll be able to view the entire post in your email app.

Thanks for reading.

Bracketology (2025 Edition)

As my friend Mark Newfield likes to say, the Forecasters Hall of Fame has zero members. And he’s right, of course. Yet, I do have a prediction I’m pretty confident about. Millions of NCAA Tournament brackets will be filled out this week, but none of them will be perfect. Not that I’m going out on a limb.

I watch more college basketball than I should, but my bracket is usually busted on the first afternoon. Sometimes by the first game.

You shouldn’t expect to do any better.

As many as one hundred million brackets will likely be filled out this year, like every year, but there has never been a verified perfect one. Last year, when eight seed Utah State beat nine seed TCU in game 31 of the opening round, the last perfect-to-that-point bracket was busted. Wild randomness is why March Madness is so great.

The odds of picking all 63 tournament games correctly are the odds of each game multiplied together. Those are insanely long odds. Usually, nobody gets the full first round correct. In other words, usually, nobody’s bracket gets to the opening weekend. Upsets rule.

Did you have (11 seed) North Carolina State in last year’s Final Four? I didn’t, either.

Between 1985 and 2024, there were 8.5 upsets per tournament (4.7 in the first round), on average, about 13 percent of the 63 games, according to the NCAA (which doesn’t count a nine seed beating an eight as an upset). That said, some years are bound to bust brackets. Both 2021 and 2022 each had 14 upsets; there were 10 upsets in 2023 and nine in 2024, if only three in 2007. In nine of the past 13 years, lower seeds have won at least 10 games.

Gregg Nigl, a neuropsychologist from Columbus, Ohio, has come closest so far to a perfect performance. In 2019, submitting a hastily filled in bracket – and under the influence of cold medicine – Nigl predicted the first 49 games of the tournament correctly (into the Sweet Sixteen) before seeing his streak snapped. Nigl’s bracket finally went bust on game 50 (the third game on the second weekend) when three seed Purdue defeated number two Tennessee, 99-94, in overtime. That was about a one-in-five-million level of success.

One bracket in 2017 was right through an incredible 39 games. In 2014, one bracket was alive through 34 games.

The difficulty lies in the upsets, of course. March Madness is a very high variance proposition.

Top seeds have only lost to 16 seeds twice in the seeded era – since 1979 – and both occurrences are recent (that said, 2008 was the only year all four top seeds made the Final Four). And about 60 percent of national champions are one of the four number one seeds. On average, a 13 seed knocks off a 4 seed about once per tournament; 12 seeds beat fives more than one-third of the time. The 11 and 10 seeds win about four times in ten. Six 11 seeds have made it to the Final Four: LSU in 1986, George Mason in 2006, VCU in 2011, Loyola Chicago in 2018, UCLA in 2021, and NC State last year.

Slightly more than half of one-through-four seeds lose before the second week of the tournament. Surprisingly, if a 10, 11 or 12 seed wins their first-round game, they have about a 40 percent chance of moving on to the Sweet 16. Confidence? Hot hand? Dumb luck? I don’t know.

The nine beats the eight more often than not, although Villanova won a national championship as an eight seed in 1985, the lowest ever. UConn won the national championship as a seven in 2014. North Carolina State in 1983 and Kansas in 1988 won it all as six-seeds.

As a general rule, there are many more upsets early than late. However, since 2011, at least one seven seed or lower has made it to the Final Four every year except 2019. Still, a top seed wins the tournament more often than not, including nine of the last 12.

Last season’s UConn Huskies won a second consecutive title as a heavily favored top seed, unlike 2023 when they were a four. They have an even tougher road this year as an eight seed. Since seeding began in 1979, all four two-seeds have reached the Sweet 16 only six times. A double-digit seed has advanced to the Sweet 16 nearly every year. At least one team seeded fifth or lower has advanced to the Elite Eight almost every year. And a “First Four” team usually wins a second game.

That’s a lot of variance.

It is often claimed that the odds of picking a perfect NCAA Tournament bracket are a staggering one in 9,223,372,036,854,775,808 (that’s 9.2 quintillion – a quintillion is a billion billion). To put that into perspective, if every person on the planet (about 7.9 billion people) started filling out a bracket per minute, it would take over 2,000 years to fill out 9.2 quintillion. By way of comparison, there are something like 7.5 quintillion grains of sand on the earth. You’d have a better chance of making four holes-in-one in a single round of golf than of creating a perfect bracket with those odds.

The following are much more likely than a perfect bracket.

Being dealt a royal flush in a game of Texas Hold ‘Em (one in 30,940).

Winning the Powerball jackpot (one in 292,201,338).

A roulette wheel hitting the same number seven times in a row (one in three billion).

Hitting a jackpot on a classic slot machine (meaning one with three wheels, each with 64 “stops”) (one in 262,144).

During the 2010 World Cup, Paul the Octopus picked the correct winner of eight-straight matches, including the final (his odds of doing so were one in 256).

Note, however, that these calculations assume every game is a 50:50 proposition, which of course isn’t the case. Duke math professor Jonathan Mattingly claimed the average college basketball fan has a far better chance of achieving bracket perfection than one in 9.2 quintillion. According to Mattingly, adjusting probability based on seeding, the odds of picking all 63 games correctly is more like one in 2.4 trillion. Using a different formula, DePaul mathematician Jay Bergen calculated the odds at one in 128 billion. The NCAA says it’s one in 120 billion.

Whatever the true odds, if you are really lucky, your perfect bracket will last about halfway through Thursday’s opening day games.

That said, there is a chance.

The highly unlikely happens surprisingly often, of course. In 2009, New Jersey grandmother Patricia Demauro set a craps world record over four hours and 18 minutes by rolling a pair of dice 154 times before crapping out. Her odds of doing that were one in 5.6 billion.

In Monte Carlo, on August 18, 2013, a Roulette ball landed on black 26 times in a row – the longest such streak ever recorded, with odds against of 136,823,184 to one. As the streak lengthened, gamblers lost millions betting on red, believing that the odds changed with the length of the run of blacks – a classic exhibition of the gambler’s fallacy.

In June 2002, electrician Mike McDermott won £194,501 on the UK National Lottery after correctly choosing five numbers and the bonus ball. Fast-forward four months to October and Mike was still playing. He matched the exact same five numbers and bonus ball that he had in June, having continued to play them out of habit. He picked up another £121,157. The odds of Mike winning twice with the same numbers were over five trillion to one.

Despite remarkably long odds, Richard Lustig has won the lottery seven different times, Roy Sullivan survived being struck by lightning seven times, and the roulette wheel at the Rio in Las Vegas landed on 19 seven consecutive times.

Motoyuki Mabuchi went all-in with four aces in the main event hand of the 2008 World Series of Poker but lost to Justin Phillips’ royal flush. Even worse for Mabuchi, the final diamond ace that handed Phillips victory came with the last card drawn. As Ray Romano said, “How many times you gonna see that?!”

The odds of this exact showdown occurring were about one in 165 million. That’s a bad beat.

It seems like it ought to be easier than that to pick winners and better brackets. There is no spread involved and a full season of games has been played, allowing us to evaluate the teams with a significant amount of data. But the short answer is that there are simply too many variables and too much randomness involved to think that we can succeed in picking all those winners.

To track the evolution of the universe for even a millisecond, astrophysicists would have to pinpoint billions of individual stars and then use paired-gravity calculations to compute all the forces at play. It would take years.

Henri Poincaré proved back in 1887 that the motion of three objects within the same system is non-repeating and thus chaotic. In other words, the historical pattern has no predictive power whatsoever with respect to where the objects will be in the future. There is no possible algorithm to solve this problem and no predictable pattern. Accordingly, nobody can solve the three-body problem and predict the future of such a system. That we cannot expect to predict the movements of just three independent variables more than suggests nobody should expect to be able to forecast the future.

There are more ways to arrange a 52-card deck than there are atoms on Earth, which means that every time you shuffle a deck of cards, the same order of cards has probably never been seen in human history and may never be seen again.

NARRATOR: “Next time you are tempted to make a market prediction, you might recall that the global economy has a few more than 52 variables.”

The late Daniel Kahneman described randomness as noise and was convinced that “bias has been overestimated at the expense of noise.” Moreover, “noise and bias are independent sources of error, so that reducing either of them improves overall accuracy... and the procedures by which you would reduce bias and reduce noise are not the same.” Indeed, “as a first rule, there is more noise than people expect, and there’s more noise than they can imagine because it’s very difficult to imagine that people have a very different opinion from yours when your opinion is right, which it is.”

Despite that reality, according to a study undertaken by the CFP Board, 88 percent of consumers and 30 percent of financial advisors think it’s easy to manage money. However, everyone should agree that predicting what will happen in the world and in the markets has many more variables and requires much more complex thinking than predicting the binary outcomes of basketball games.

REMINDER: We aren’t very good at picking basketball games.

Stats guru Ken Pomeroy ran a million tournament simulations this year and got 55 different winners. Even Bryant won once. Duke has the best chance of winning, by his calculations, a 22.9 percent chance2; St. Francis the least, essentially zero.

As the great playwright Tom Stoppard understood: “[T]here is really, really good news if you end up feeling lucky rather than clever.”

As Stoppard postulated in his play, The Hard Problem: “In theory, the market is a stream of rational acts by self-interested people; so risk ought to be computable. But every now and then, the market’s behavior becomes irrational, as though it’s gone mad, or fallen in love. It doesn’t compute. It’s only computers compute.”

It doesn’t compute, of course, because markets are driven by people, who may be self-interested, but who aren’t necessarily rationally self-interested at any given time. They are mere human people, not computer people. They are yearning, hurting, illogical, infuriating – driven by the attraction Newton left out. We want binary questions and simple answers in a world far messier and more complicated than that.

As Nobel laureate Robert Shiller has clearly explained, “The U.S. stock market ups and downs over the past century have made virtually no sense ex post.”

Let’s stipulate that forecasting the future is almost impossibly unlikely and that predicting how humans will perform under stress is incredibly difficult. By most models, even the best team in the NCAA tournament typically has only something like a 15-20 percent chance of winning it all. That’s why your office pool can be won by Janice in Accounting who has never seen a game and picks her winners based upon team colors3 and mascots.

In related news, we shouldn’t be surprised when the market remains “irrational” far longer than seems possible. But we are.

Still, you can improve your odds a bit and maybe win some money in a pool (because nobody is very good at this – in the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king).

The number of players in the pool you’re playing is the most important factor for determining your bracket strategy. If you are in a smaller pool, you’ll want to take fewer risks. Chalk is your friend. If you’re in a larger pool, you’ll want to be risk-on (don’t pick Duke; instead, think like a value investor). Pay attention to any special rules for your specific pool and adjust your picks accordingly.

For upsets generally, you can check public bracket metrics to see which teams on each seed line are the most popular and consider “fading” them for your upset selections. Betting markets are the best available measure of a true win probability projection for a specific game. Accordingly, if (for example) a 4-seed is being picked to move on in 90 percent of brackets but the betting market only gives it a 75 percent chance of winning, that might be a 13-seed worth picking. Especially in big pools, you might want to fade the most picked teams.

BOTTOM LINE: The world is messier, more random, less predictable, more surprising, and less linear than we assume.

That’s great for the NCAA Tournament, of course, and bad for your bracket. It’s also more than a bit problematic elsewhere. But, at least in the context of bracketology, it sure is fun.

Traders Gonna Trade

In 1991, UNLV was the defending national champion in basketball and came into the Final Four unbeaten, unchallenged, and heavily favored. Many thought it was the greatest college basketball team of all-time. In the national semi-final, the Runnin’ Rebels met my Duke Blue Devils, up to that point a perennial bridesmaid and a team UNLV had destroyed the previous year, 103-73, in the most lop-sided championship game in NCAA Tournament history.

It was U-G-L-Y in 1990 and most people expected more of the same in 1991. Happily, that wasn’t what happened.

But my story here isn’t about the game itself or even the tournament, exactly. In those days, Wall Street trading houses had big tournament pools that featured high entry fees (and thus big prizes for winners) with serious bragging rights at stake. Significantly, because there were lots of traders involved, lots of trading went on. You could call most any major shop and get a two-sided market on any team to win the tournament.

That fact is noteworthy because one particular trader was convinced that UNLV was going to repeat as champions. More particularly, he was convinced that Duke would not win the tournament and shorted the Blue Devils big without hedging — expecting to profit handsomely when elimination ultimately came. In other words, he was looking to make big money on the trade and not just on the spread. However, losing (Duke winning) would mean not just lost potential profits — he would have to ante up real cash. As the expression goes, he was picking up nickels in front of a steamroller.

Our poor schlub was pretty nervous on the Monday after the UNLV upset, but Duke still had to beat Kansas that evening (ironically, it was April Fool’s Day) to win the title and for the trader to have to cover his shorts. He feigned confidence, of course, but nobody was fooled. When Duke prevailed over the Jayhawks, 72-65, the fool was six figures (plus) in-the-hole.

The trader made good — sheepishly and painfully — but the brass learned a lesson. Thereafter, the big firms no longer allowed employees to organize tournament pools and trading on the pools that existed was strictly prohibited. It was even enforced. Rumor had it that this was part of a quiet agreement between regulators and internal compliance officials, who were understandably concerned about what had gone on. Wall Street pools still existed after that, of course, but they were now run exclusively on the buy-side; we on the sell-side still played, but it wasn’t the same. There wasn’t any trading that I’m aware of. And that’s a good thing.

Traders are going to trade. And without careful oversight, position limits, and careful hedging, it’s inevitable that people will get themselves in big trouble. That lesson applies to NCAA Tournament pools and to any security you might want to name. It applies to your personal portfolio, too.

Totally Worth It

Warren Buffett has long imparted a probability lesson in the form of a wager, offering $1 million via the Berkshire Hathaway NCAA tournament bracket challenge if any employee got every March Madness pick right. This year, he’s tweaking the odds to make it easier. The prize will be awarded if an entrant picks the winners to at least 30 of the 32 first-round games. The odds remain long, but not nearly so long as they were. Buffett also offers what he calls the “lollapalooza” prize: $1 million a year for life if a single entrant correctly predicts the winners of each of the first 48 games ahead of the tournament’s Sweet 16. Depending upon how likely one estimates the likelihood of upsets, the chances of picking a perfect bracket are about 1 in 128 billion (see above). Nobody ever has.

Feel free to contact me via rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or on Twitter (@rpseawright) and let me know what you like, what you don’t like, what you’d like to see changed, and what you’d add. Praise, condemnation, and feedback are always welcome.

Dylan and Schubert make a powerful brew.

Americans spent $13.7 billion on sports wagering in 2024, +25 percent year-over-year, according to the American Gaming Association, even though it is still illegal in the three largest states. By way of comparison, they spent about $9 billion on going to the movies.

Of course, the easiest way to share TBL is simply to forward it to a few dozen of your closest friends.

You may hit some paywalls below; some can be overcome here.

This is the best thing I’ve read recently. The sweetest. The saddest. The most disconcerting. The most interesting. The most insightful. The best thread. When do television shows get good? 150 years of stock market crashes. How Covid changed us. The 100 best TV performances. Bureaucracy run wild. What Congress is really like. Fifteen big losers; Fifteen big winners. Fan fiction.

Please send me your nominations for this space to rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or via Twitter (@rpseawright).

Benediction

Sometimes Carrie Underwood sings in church. One of those times is today’s benediction.

We live on “a hurtling planet,” the poet Rod Jellema informed us, “swung from a thread of light and saved by nothing but grace.” To those of us prone to wander, to those who are broken, to those who flee and fight in fear – which is every last lost one of us – there is a faith that offers love and hope. And may grace have the last word. Now and forever. Amen.

As always, thanks for reading.

Issue 185 (March 18, 2025)

The term “March Madness” was first used by Henry V. Porter, a high school official in Illinois, in 1939. But the term wasn’t used in reference to college basketball until 1982, when CBS broadcaster Brent Musburger used it during that year’s coverage.

Pomeroy’s model says this year’s Duke squad is the strongest team of the past 25 years. That means, the last time a team was this statistically commanding, Duke coach Jon Scheyer was in middle school and Duke’s players weren’t even born. The Blue Devils are still much more likely to be eliminated than to win it all. Last year, Connecticut broke a streak of 15 consecutive tournaments where the top overall seed failed to win the national championship (absurdly, the NCAA made Auburn this year’s top overall seed).

Over the last 20 years, Louisville in 2013 and Baylor in 2021 are the only teams that have cut down the nets and cried to One Shining Moment, without blue being part of the primary color scheme to their uniforms.

love it. bet the house on Duke. what could possibly go wrong.

GTHc!

Another winning entry! But . . .

. . . after reading many posts of yours confirming how difficult--well-nigh impossible--it is to predict future stock prices, and how spectacularly wrong much investment advice turns out to be, I do have to wonder why you sometimes seem to look down on index investing or other 'safe' investing tools like annuities. Based on some very quick internet research, from 2000 through 2024, the S&P 500 has gone up an average of 7.85% per year, while inflation has averaged around 2.6% per year. So why not just go with an index fund instead of hoping that you or your chosen investment advisor actually is better than the proverbial dart board? Or perhaps even safer, if you don't need access to funds for a substantial time period (say a roll-over when changing jobs well before retirement), why not put those dollars in an annuity that guarantees 5-6% returns compounded annually so long as you don't withdraw them until well down the road?

Apologies if you covered this elsewhere, and I missed it.