2024 Forecasting Follies

TBL's annual look at the "best" in human forecasting.

Humans, unlike any other living thing, can imagine the world as it isn’t – a different future. That doesn’t mean we’re any good at it. Even the most interesting futurists – science fiction writers – miss the boat a lot. By a lot. Nothing looks more dated than old science fiction.

For example.

Blade Runner’s heroine, Rachael (Sean Young), seems to be a beautiful young woman but is an organic robot instead. “She” is real enough to pass a Turing Test, imbued with memories extracted from a human being. Los Angeles police detective Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford) knows she isn’t human but falls for her anyway. Yet, when Rick wants to invite Rachael out for a drink, he doesn’t use a mobile device. He calls her up from a graffiti-marred payphone. At least it’s a videophone.

We can imagine getting to artificial life, downloading and uploading a human mind. But everyday life in a society that sophisticated still looks pretty much the same, save a few monstrous technological leaps, like hovercraft.

The first lesson in making predictions: Don’t make them.

Few follow that advice. Herein is my annual missive looking at the previous year’s bad forecasts and predictions. As always, they are legion. And often funny.

If you like The Better Letter, please subscribe, share it, and forward it widely.

If you’re new here, check out these TBL “greatest hits” below.

NOTE: Some email services may truncate TBL. If so, or if you’d prefer, you can read it all here. If it is clipped, you can also click on “View entire message” and you’ll be able to view the entire post in your email app.

Thanks for reading.

2024 Forecasting Follies

In the Star Trek universe, the Kobayashi Maru is a Starfleet Academy training exercise for future officers in the command track. It takes place on a replica of a starship bridge with the test-taker as captain. In the exercise, the cadet and crew receive a distress signal advising that the freighter Kobayashi Maru has become stranded in the Klingon Neutral Zone and is rapidly losing power, hull integrity, and life support.

The cadet is seemingly faced with a choice (a) to attempt to rescue the freighter’s crew and passengers, which involves violating the Neutral Zone and potentially provoking the Klingons into an all-out war; or (b) to abandon the freighter, potentially preventing war but leaving the crew and passengers to die. As the simulation is played out, both possibilities are set up to end badly. Either both the starship and the freighter are destroyed by the Klingons or the starship is forced to wait and watch as everyone on the Kobayashi Maru dies an agonizing death.

The objective of the test is not for the cadet to outsmart or outfight the Klingons but, rather, to examine the cadet’s reaction to a no-win situation. It is ultimately designed as a test of discipline and character under stress.

However, before his third attempt at the test while a student, James T. Kirk surreptitiously reprograms the simulator so that it became possible to rescue the freighter. When questioned later about his ploy, Kirk asserts that he doesn’t believe in no-win scenarios. And he doesn’t like to lose. So he changed the game. Thus, for Trekkies, the test’s name is used to describe a no-win scenario as well as a solution that requires that one change the game to jerry-rig a solution to the proffered problem.

For would-be market experts, their Kobayashi Maru is a public market target, most often included in an annual market preview publication. It’s an expected part of the gig. Similarly, when a Wall Street strategist, economist, or even a run-of-the-mill investment manager or analyst gets a crack at financial television, he or she is routinely asked, often as almost an afterthought, to give a specific target forecast for the market. Instead of thinking like Captain Kirk and wisely objecting to the premise of the question, the poor schlemiel answers and, once matters play out, is inevitably shown to have been less than prescient.

As I like to say, one forecast that is almost certain to be correct is that market forecasts are almost certain to be wrong.

Annually, I take a look at such predictions from the previous year and they are almost uniformly lousy. Moreover, when somebody does get one right or nearly right, that performance quality is not repeated in subsequent years. That’s because, at best, complex systems – from the weather to the markets – allow only for probabilistic forecasts with very significant margins for error and often seemingly outlandish and hugely divergent potential outcomes. Chaos theory establishes as much. Traditional market analysis has generally failed to grasp the inherent complexity and dynamic nature of the financial markets, which chaotic reality goes a long way towards explaining highly remarkable and volatile outcomes that seem inevitable in retrospect but were predicted by almost nobody.

2024 wasn’t any different. As always, I lead with Wall Street, the markets, and the economy, the objects of my day job.

How will the market perform? The answer to that oft-asked question, based upon data to date, is that it almost always provides between a 33 percent loss and a 50 percent gain, but there is about a 1-in-20 chance it could be outside that range. It was no different in 2024, but the relative normality of the year didn’t improve the forecasts any.

As ever, Wall Street denizens are often wrong but never in doubt.

A few have begun to concede that forecasting might be a problem (here, for example). Still, even when they concede it has never worked, they still think “it might work for us.”

The median year-end Wall Street 2024 forecast for the S&P 500 was 5,068, according to FactSet, implying an annualized gain of roughly 6 percent for the year.

Citigroup, Deustche Bank, and Goldman Sachs were the most bullish, calling for a year-end target of 5,100 (from a starting point of 4,770). Morgan Stanley was negative on 2024, calling for a year-end target of 4,500 and the avoidance of technology. Morgan Stanley’s Chief Strategist, Mike Wilson, finally capitulated in May. Morgan Stanley’s Chief Economic Strategist blew her call, too.

The most bearish was JPMorgan Chase, whose team was led by Marko Kolanovic, dubbed “Gandalf” for his alleged foresight. He was elected to the Institutional Investor Hall of Fame in 2020. His 2024 year-end target was 4,200, down almost 9 percent. The year ahead will be “another challenging year for market participants,” Kolanovic opined. Gandalf was fired in July.

Bloomberg cast a wider net, looking at more than 650 market calls. Amundi and Vanguard were among those predicting “mild” recessions. To BNY Mellon Wealth Management, it was to be “a healthy and welcome slowdown.” Stifel called for a range-bound S&P and growth underperformance. “Tilt to fixed income,” insisted Franklin Templeton. “Bonds have their moment,” BNY Mellon Wealth proclaimed.

There were a few bulls. UBS Asset Management said if its base case soft landing was achieved, “global equities will comfortably ascend to new all-time highs in 2024.” There were 57 all-time highs in 2024.

The most bullish call in Sam Ro’s compilation was 5,500, up nearly 20 percent, by Capital Economics. That’s not bad, still well short of actual returns.1

Nobody believes there are sure things in markets, but many alleged experts thought high-quality U.S. bonds were pretty close as 2024 began. The consensus on Wall Street was that interest rates had peaked for the economic cycle. Traders in futures markets were betting the Federal Reserve would lower rates at its meeting March 20, followed by another four or five quarter-point cuts throughout the year.

Nope.

The S&P closed 2024 at 5,881.63, up 25.02 percent on the year, including dividends. Bonds had another lousy year, how lousy it was depended upon which index you use as a proxy for bonds overall. For example, the S&P U.S. Aggregate Bond Index returned 1.82 percent in 2024.

And still no recession. Indeed, market economists have no better record than strategists.

Rate predictions failed, too.

Even the Fed itself, with more and better information than anyone, can’t predict what interest rates will do.

Bank of America said the S&P peaked at the end of July; as of the end of 2024, it had gained over 7 percent in the second half of the year. Jim Rogers was negative, too. Jim Rickards predicted a 50 percent crash. Gary Marcus called for the AI revolution to collapse in 2024. Even The Motley Fool predicted a crash. So did BCA Research. Strategist David Rosenberg, who had been maximally bearish about 2024, finally capitulated in December and apologized for his incessant bearishness.

Jeff Gundlach kept calling for a recession that wouldn’t come (he wrongly loved value and foreign stocks and called for S&P underperformance, too). He was not alone.

The perma-bears still hate the market, waiting for an inevitable downturn to prove them “right” (Hussman; Dent; Nations; Kiyosaki; Grantham; Burry).

As always (over the most recent 10 years, fewer than 10 percent of money managers have outperformed), stock-pickers had a poor year in 2024.

A year ago, Barron’s asked its roundtable of alleged experts for their best 2024 ideas, “the next Nvidia.” None did very well. Indeed, most picks underperformed the market, many lost money, and only one made one-third as much as NVDA’s +171 percent.

John W. Rogers, Jr., founder, chairman, co-CEO, and chief investment officer of Ariel Investments, did best (annual return in parenthesis). He picked Adtalem Global Education (+54 percent), Stericycle (currently subject to a tender offer at a healthy premium), Sphere Entertainment (+19 percent), Envista Holdings (-20 percent), and Leslies (-68 percent). William Priest, chairman, co-chief investment officer, and a portfolio manager at TD Epoch, picked Meta (+66 percent), which handily beat the S&P 500, but his other four picks did not. RELX earned 16 percent, but the other three did poorly.

Evolution Gaming Group lost 35 percent, ON Semiconductor lost 25 percent, and Keyence lost 7 percent. David Giroux, CIO of T. Rowe Price Investment Management, picked RTX, a winner (+40 percent), Fortive (+2 percent), which underperformed the S&P 500 by about 23 percent, Waste Connections (+16 percent), which underperformed by nearly 10 percent, Canadian Natural Resources (-1 percent), and Biogen, which lost more than 40 percent. Scott Black, founder and president of Delphi Management, picked four stocks, all of which underperformed the index: Everest Group (+5 percent), Diamondback Energy (+11 percent), Oshkosh (-11 percent), and Global Payments (-11 percent).

Barron’s made its own picks, too. It provided a top ten list of stocks to outperform in 2024. Only one did so: Alphabet (+36 percent). Another marginally outperformed the S&P 500: Berkshire Hathaway (+25.49 percent). The other eight underperformed, with four in the red during a year of +25 percent returns: Alibaba Group Holding (+12 percent); MSG Sports (+12 percent); BioNTech (+8 percent): Chevron (+1 percent); Pepsi (-7 percent); U-Haul (-9 percent); Barrick Gold (-12 percent); and Hertz (-65 percent).

Wall Street analysts, in the aggregate, had Tesla stock losing about 3.5 percent in 2024; it was up a whopping 63 percent.

It always seems to be a stock-picker’s market, but few pick the right stocks.

Predictions have a long and ignominious history, especially about the future.

In 1876, the President of Western Union, William Orton, dismissed the telephone as a “toy” when Alexander Graham Bell offered to sell him the patent for $100,000. According to Orton, “The idea is idiotic on the face of it. Furthermore, why would any person want to use this ungainly and impractical device when he can send a messenger to the telegraph office and have a clear written message sent to any large city in the United States?”

Hollywood film producer Darryl Zanuck of 20th Century Fox was sure the appeal of television would be short-lived. In 1946, he said: “Television won't be able to hold on to any market it captures after the first six months. People will soon get tired of staring at a plywood box every night.” The average American spends about five hours per day watching TV.

In 1950, Waldemar Kaempffert, science editor of The New York Times, foresaw a world where all food, “even soup and milk,” would be delivered to people’s homes in frozen bricks, and chemical factories would convert “rayon underwear” into sweets. Today, there’s a market for dehydrated meals, but they are mostly the preserve of astronauts, outdoor adventurers, and doomsday preppers.

In 1956, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev was addressing Western ambassadors at the Polish embassy in Moscow. He told his audience that that communism’s defeat of capitalism was inevitable. “History is on our side,” he said. “We will bury you.” Thirty-three years later, communism collapsed, and two years after that the Soviet Union was dissolved.

In 1966, Time magazine boldly predicted: “Remote shopping, while entirely feasible, will flop – because women like to get out of the house, like to handle merchandise, like to be able to change their minds.” In 2024, e-commerce sales totaled about $6.3 trillion.

When he was a teenager, Frank Sinatra was rejected as a singing waiter at The Rustic Cabin, an Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey tavern, after an audition. His mother went to bat for him and the tavern relented and hired him, but only because his mother had local clout. Bandleader Harry James would eventually discover him there.

In 1995, Robert Metcalfe, founder of digital electronics company 3Com, said: “I predict the internet will soon go spectacularly supernova and in 1996 catastrophically collapse.” According to the latest available data, the average person spends about seven hours per day on screens connected to the internet.

In 2007, Steve Ballmer, then the CEO of Microsoft, said, “There’s no chance that the iPhone is going to get any significant market share. No chance.” There are 46 iterations of iPhone and about 1.4 billion users.

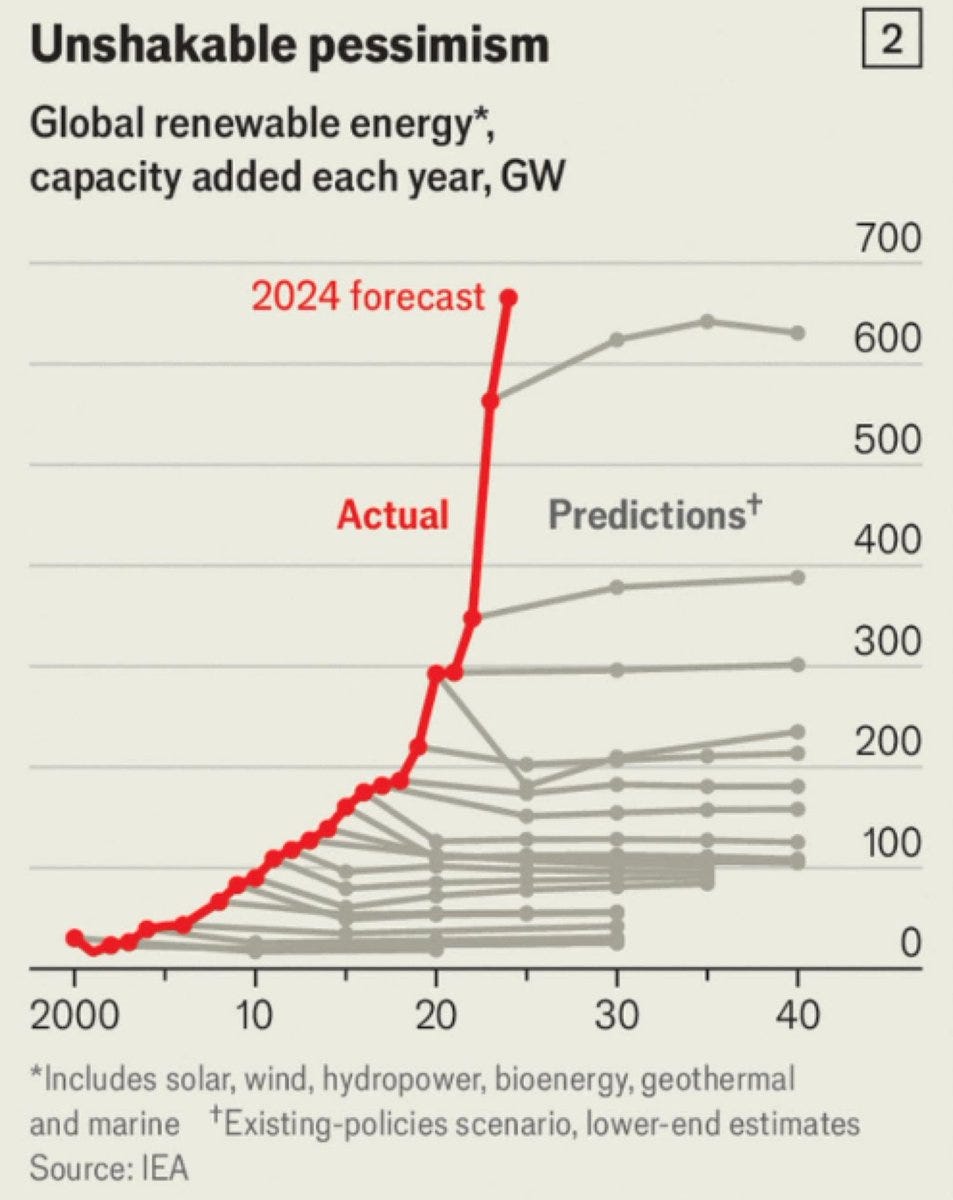

So far, since 2010, solar energy has outperformed every single prediction. The same outperformance also exists for renewables as a whole.

Again, the universe of bad predictions is essentially unlimited.

As ever, 2024 had its share of clunkers in a wide variety of contexts.

Many, including Rob Reiner, were sure that Vice President Kamala Harris would be elected president (after a whole slew of folks predicted President Biden’s reelection, including Chris Matthews; my favorite is here). “A woman gave birth to each and every one of us. Tomorrow a woman will give birth to a renewal of our Democracy,” Reiner said. Some thought she would win big (my favorites are here and here).

Dilbert cartoonist Scott Adams forecast “a landslide of election rigging claims” with “no winner.”

“I think markets crash tomorrow if there’s a conviction [of former President Trump in New York],” Breitbart’s John Carney proclaimed. On May 31, 2024 – the first full day markets were open after Mr. Trump was convicted – the Dow climbed about 575 points, posting what was at the time its best day of 2024.

NYU’s Scott Galloway predicted that Elon Musk would sell Twitter.

Wealthfront recently filed to liquidate its $1.3B Risk Parity Fund. From its January 22, 2018 inception through November 1, 2024, the fund lost 2.8 percent of its value, compared to a 66.6 percent cumulative gain for the U.S. 60/40 mix over that span.

MLB player Tucupita Marcano was permanently banned from baseball in 2024 for betting on hundreds of games, many in which he participated. He lost over 95 percent of those bets.

Here’s my favorite: Greg Amsinger of the MLB Network said, before the start of the game, “Don’t take this the wrong way, but we are already on no-hitter alert. Yoshinobu Yamamoto, before he throws a single pitch tonight against the Marlins.” Miami’s Jazz Chisholm took Yamamoto’s first pitch of the game deep.

The future is always imaginary, by definition. By the time we know, it’s no longer the future.

As should be obvious by now, we are monumentally poor at making predictions. Wharton psychologist Philip Tetlock examined decades of predictions about political and economic events and found that “the average expert was roughly as accurate as a dart-throwing chimpanzee.” And the markets keep making monkeys out of forecasters.

Here’s the bottom line.

We’re dreadful at predictions. As my friend Mark Newfield likes to say, the Forecasters’ Hall of Fame has zero members. See above.

When they’re right, it’s almost always luck, not skill (more here). Lots of reputations have been made being right once in a row. For example, Michael Moore, famous for being one of the few people who predicted Donald Trump’s election win in 2016, confidently declared that Mr. Trump would not win again in 2024 (Do The Math: Trump Is Toast). That’s further proof that even a stopped clock is right twice a day.

Even if we knew the future, we’d probably make the wrong trade (see for yourself, here). When Sam Bankman-Fried was at Jane Street Capital (before he became famous for FTX and convicted of fraud), he built a system to get the 2016 U.S. Presidential election results before any media outlet could broadcast them. It worked, and the Jane Street team knew Donald Trump had shocked the world and defeated Hillary Clinton before anyone else. But they still managed to lose money – a ton of money ($300 million!) – on the trade because they bet against U.S. markets into a big post-election rally. More examples here.

And if we knew the future, and made the right trade, we’d almost surely bail too soon to take real advantage. My friend, Wes Gray, analyzed returns from January 1, 1927 through December 31, 2016 for the 500 largest American firms and created “look-ahead” five-year portfolios of the best performing stocks during that period. These hypothetical portfolios would have compounded at an annualized 29 percent (capacity restraints and, you know, our inability to predict the future wouldn’t allow this to happen in real life, of course). Such a “best possible” approach would still have yielded a 76 percent drawdown (as well as nine other drawdowns in excess of 20 percent) and been more volatile than the market. The “best possible long/short” approach would have yielded a CAGR of 46 percent but a drawdown of 47 percent (as well as six other drawdowns in excess of 20 percent) and been more volatile than the market. Who wouldn’t have bailed or fired the money manager (say, Biff Tannen Investments) if that happened? Best guess: Nobody.

Warren Buffett’s advice on forecasts remains spot-on.

“We have long felt that the only value of stock forecasters is to make fortunetellers look good. Even now, Charlie [Munger] and I continue to believe that short-term market forecasts are poison and should be kept locked up in a safe place, away from children and also from grown-ups who behave in the market like children.”

In early December, the founder and head of a Singapore-based hedge-fund that had survived for over 25 years sent a four-page letter to investors with bad news. The fund was closing. It had lost 7.9 percent in November alone and was down over 35 percent for 2024 (its benchmark of Asian stocks outside of Japan was up 8.6 percent). At least the candor was refreshing. “I have come to the realization that I am not good at what I am doing but I guess some of you may have sensed that already,” he wrote. He didn’t stop there.

“I pretty much missed all the major themes in the last two years. I was hopelessly out of sync with the market, buying when I should be selling and selling when I should be buying. We got whipsawed several times this year even as we got some facts correct.”

The lesson he drew: “sometimes the best investments are precisely the ones you cannot explain and probably made no sense.”

At least one guy seems to have figured things out, even if it was the hard way.

Lifetime Achievement Award

Nobel laureate Paul Krugman ended his nearly 25-year run as an opinion columnist for The New York Times in December. He is a terrific economist but a dreadful forecaster (the former is rare, indeed; the latter, not so much). As such, he has been an annual regular herein and will be missed.

A few of his “greatest hits” follow.

Dr. Krugman predicted that the internet would be no more impactful than a fax machine. He thought the Euro would fail in short order. He expected Donald Trump's election in 2016 to cause permanent market doom.

Fortunately, there is no shortage of poor forecasters vying for his place and this space.

Happy Retirement, Paul!

Totally Worth It

Feel free to contact me via rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or on Twitter (@rpseawright) and let me know what you like, what you don’t like, what you’d like to see changed, and what you’d add. Praise, condemnation, and feedback are always welcome.

Of course, the easiest way to share TBL is simply to forward it to a few dozen of your closest friends.

You may hit some paywalls below; some can be overcome here.

This is the best thing I’ve read recently. The loveliest. The funniest. The creepiest. The most powerful. The most insightful. The most intriguing. The most interesting. Scary?

Please send me your nominations for this space to rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or via Twitter (@rpseawright).

Benediction

We live on “a hurtling planet,” the poet Rod Jellema informed us, “swung from a thread of light and saved by nothing but grace.” To those of us prone to wander, to those who are broken, to those who flee and fight in fear – which is every last lost one of us – there is a faith that offers grace and hope. And may love have the last word. This Christmas and forever. Amen.

As always, thanks for reading.

Issue 180 (January 3, 2025)

I once read a story about an anthropologist who had gone to study an uncontacted tribe in the Amazon. Not sure how he got to it, but he did this thing where he would place an object somewhere in a room and ask a tribe member to look for it. He then noticed that if he placed the object somewhere high, they never found it. The problem? There was no word for 'up' in their language, so they had no concept of looking up. Predictions fail because of priors: you can't imagine what you have no conception of.

PS: I love your writing.

It’s great to have some new Better Letters from ya Bob. I’ve missed ya. And I’m glad you’ve started the year reminding us what Yogi Berra once said - It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future. Happy New Year.