The Better Letter: Wash Your Hands

Plus inspiration, an update, the importance of truth, comfort, joy, and more

The human spirit can be amazing and inspiring. Watch (and listen to) the Toronto Symphony play Aaron Copland’s Pulitzer Prize winning Appalachian Spring (drawn from the Shaker hymn, Simple Gifts) from their homes.

I can’t expect to inspire you this week, or any week, but we do have significant issues to consider, all related to the current global coronavirus pandemic.

If you like The Better Letter, I hope you will subscribe (it’s free to get every edition of TBL delivered to your in-box) and share it widely.

Wash Your Hands

No instruction has been more consistent throughout the coronavirus crisis than the insistence that we wash our hands. Pretty much all the time. A lot more thoroughly and for a lot longer than we’re used to. The reminders are insistent, too, and sometimes annoying.

But they are important. Therefore, it is appropriate that we recall the tragic story of the patron saint of hand-washing. He’s Ignaz Semmelweis, a 19th Century Hungarian obstetrician who found lasting scientific fame, but only posthumously.

Semmelweis discovered that the often-fatal puerperal fever, sometimes called “childbed fever,” common among new mothers in hospitals at the time, could essentially be eliminated if doctors simply washed their hands before assisting with childbirth. Semmelweis observed that a particular obstetrical ward suffered unusually high instances of the disease and that doctors there often worked in the morgue right before aiding in childbirth but had not washed their hands in between. He speculated that “cadaverous material” could be passed from doctors’ hands to patients, causing the disease. He thereupon initiated a strict handwashing regimen at his hospital, using a chlorinated solution, for all who would assist in childbirth. Death rates plummeted.

Semmelweis expected a revolution in hospital hygiene as a consequence of his findings, but it didn’t come.

His hypothesis, that there was only one cause of the disease and that it could be prevented simply through cleanliness, was extreme at the time and ran counter to the prevailing medical ideology, which insisted that diseases had multiple causes. Despite the practical demonstration of its effectiveness, his approach was largely ignored, rejected, or even ridiculed. Things got so bad that Semmelweis was ultimately dismissed from his hospital post and harassed by the medical community in Vienna, forcing him to move to Budapest.

The story gets even stranger from there. In Budapest, Semmelweis grew increasingly outspoken and hostile towards physicians who refused to acknowledge his discovery and implement his protocols. Vitriolic exchanges ensued, in medical literature and in letters, and Semmelweis was eventually lured to an asylum where his opponents had arranged for his incarceration. He was beaten severely and put in a straitjacket. He died within two weeks.

The Semmelweis approach only earned widespread acceptance many years after his death, when Louis Pasteur developed the germ theory of disease (which offered a theoretical explanation for the Semmelweis findings) and Joseph Lister, acting on the French microbiologist’s research, practiced and operated using hygienic methods to great success. As a consequence, Semmelweis is today considered a pioneer of antiseptic procedures and something of a martyr.

Psychiatrist Thomas Szasz (highly controversial himself) summed things up aptly.

“[I]t can be dangerous to be wrong, but, to be right, when society regards the majority’s falsehood as truth, could be fatal. This principle is especially true with respect to false truths that form an important part of an entire society’s belief system. …In the modern world, they are medical and political in nature (emphasis supplied).”

What has come to be known as the “Semmelweis Reflex” is our tendency to reject new evidence or new knowledge when it contradicts our established norms, beliefs, or paradigms.

The Simmelweis Reflex and other decision-making biases compromised the containment of COVID-19. In classic examples of the planning fallacy, governments have consistently underestimated exposure and overestimated their control of the situation. For example, less than a month ago, U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson spoke of shaking hands “with everyone” and business as usual, while Italy was in disaster mode. He has since reversed course, closing schools and imposing a societal lockdown, and contracted the disease himself.

Stopping COVID-19 will require harsh and difficult measures. St. Louis Federal Reserve President James Bullard suggests that we “[f]rame this as a massive investment in U.S. public health.” It is also a massive investment in survival. Yet, in classic displays of confirmation bias and overconfidence, individuals young and old have readily latched onto narratives that suggested the pandemic might be a general threat, but isn’t much of a threat to them.

When we grab a glass of what we think is apple juice, only to take a sip and discover that it’s actually ginger ale, we react with disgust, even when we love the soda. We quite naturally try to jam the facts into our pre-conceived notions and commitments or simply miscomprehend reality such that we accept a view, no matter how implausible, that sees a different (“alternative”) set of alleged facts, “facts” that are (conveniently) used to support what we already believe.

As C.S. Lewis wrote in The Magician’s Nephew, a children’s book that is much more than that, “What you see and what you hear depends a great deal on where you are standing. It also depends on what sort of person you are.” If you want to be the sort of person your children (real or potential) look up to, take this crisis seriously. When treatments for COVID-19 are developed and, ultimately, a vaccine produced, we’re all going to have to take our medicine, literally and figuratively. Until then, stay inside. Practice social distancing. Follow the recommended procedures.

And don’t forget to wash your hands.

Totally Worth It

Here are some recent stories I found interesting, noteworthy, important, fun, or just plain weird.

The best thing I read this week. Don Giuseppe Berardelli, a 72-year old priest in Italy suffering from the coronavirus, gave up his ventilator for a younger patient and has died. Survey says: 12 percent of at-home workers skip video due to lack of clothes. NASA fixes Mars probe by hitting it with shovel. Online toilet paper calculator will tell you just how long your stash will last. NYC shortage: dogs to adopt.

Mixed Media: The best things you’ll see today (image / video). Trust me and have a look here for the pictures alone. The New York Times sent dozens of photographers to capture once-bustling public places around the world – beaches, fairgrounds, restaurants, movie theaters, tourist spots and train stations – that are now empty amid the coronavirus pandemic. Neil Diamond performs a COVID-19 version of “Sweet Caroline” – “Hands, washing hands…” (video). What staying six feet apart looks like. What it looks like from space when everything stops. Cowboy Museum puts head of security in charge of Twitter account, hilarity ensues. Sports broadcasters in Great Britain are generally pretty great and have a style quite different from what we’re used to in the U.S. Listen to one commentating on “two blokes in a park” (video). In Italy, a priest live-streamed mass due to COVID-19. Unfortunately, he activated the video filters by mistake (video).

Update: The Value of a Life

In last week’s TBL, I wrote about the value of a life and that value’s impact on our response to COVID-19: “How do you measure the life of a woman or a man?”

I concluded that, despite the enormous economic costs, the aggressive policies being implemented to combat the virus made sense economically. On Wednesday, Michael Greenstone and Vishan Nigam of the University of Chicago released some more detailed calculations and came to the same conclusion. The Economic Strategy Group, a group of American economics luminaries, made the same assessment, without the math: “We will hasten the return to robust economic activity by taking steps to stem the spread of the virus and save lives.” Moreover, where there are aggressive intervention measures in place during a pandemic, there is a stronger and faster recovery.

I also argued last week that such economic analysis in a crisis, while important, is unsatisfying. We are most profoundly human when we act – even at great risk – to save our fellow humans. There has been much more talk in the last week that the cost of saving lives in this pandemic is too high. President Trump wants America “reopened” by Easter. Under our Constitution, that isn’t his call, and doing so would be wrong if it were. It wouldn’t work, either.

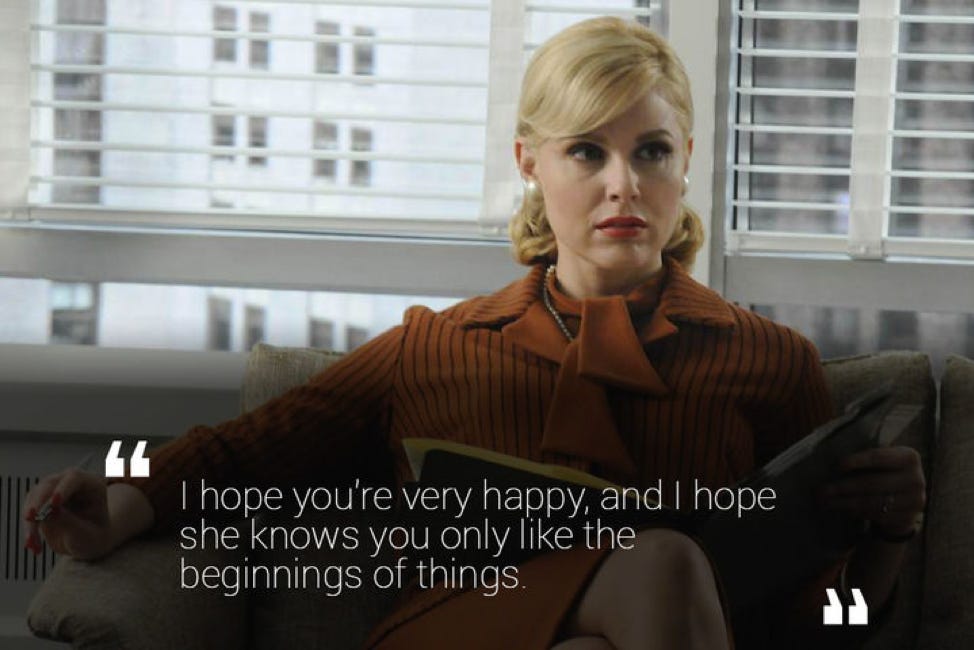

Our decision-making systems default toward immediate, tangible rewards, which means we are prone to responding to the immediate (like the current dire economic data) and to shortchange or ignore investments in intangible, longer-term initiatives. In other words, we’re all Don Drapers. We “only like the beginnings of things” and risk doom by chasing the immediate and releasing the long-term.

Much of the world is now in lockdown. By doing that, we are imposing a recession upon ourselves, by decree, in order to try to keep a terrible pandemic from getting much, much worse. It makes sense to offer hope for when we can get back to some semblance of normalcy, but the president’s goal of Easter is almost surely too soon, at least according to doctors, economists, more than a few business leaders (if not all), and the president’s own task force.

In the finance world I inhabit, we tend to focus on economic impacts dispassionately. It’s important to remember that such numbers count real people with fears, needs, and hopes. The data reflects lost jobs, weddings postponed, missed opportunities, and dreams deferred or destroyed. The cost is extremely high. Extraordinarily high.

And it’s worth every penny.

Remember, the medical data reflects the same sorts of human costs as the economic data — just more permanently. It hurts to be on lockdown. A lot. But we’re doing the right thing.

Truth Matters (especially in a crisis)

Truth is in short supply today, especially in politics. We all acknowledge that fact, albeit inconsistently and hypocritically. We’re outraged when their side lies yet are barely disappointed (and suggest it’s merely “spin”) when our side does.

John Barry's book, The Great Influenza, is generally regarded as the definitive history of the 1918 pandemic that killed 50 million people worldwide (a recent video interview of Barry about that period is available here). Of all the lessons from the 1918 catastrophe, for Barry, the clearest is that truth matters: “those in authority must retain the public’s trust. The way to do that is to distort nothing, to put the best face on nothing, to try to manipulate no one.”

If we’re honest, we expect politicians to lie, even those we agree with (at least a little), but we’re much less tolerant of it in a crisis.

That explains why Dr. Anthony Fauci (the “face of Donuts Delite”) has been such a beacon of light during these dark times. We may not demand truth often enough, but we still know it when we hear it. Dr. Fauci clearly speaks truth and speaks truth clearly. And he is unafraid to speak truth to power, but without rancor or vindictiveness.

I have no clue what his politics are, but I’d surely consider electing Dr. Fauci to the presidency right now.

Benediction

In a time when lots of us gave up more for Lent than we anticipated, listening to and singing the hymns and gospel songs I grew up is soothing. This week’s benediction is a new version of one of those old songs I love: “I Stand Amazed” by Celtic Worship.

Issue 5 (An early — it’s done and I’m bored — pandemic, sheltered in place edition: March 28, 2020)