The Better Letter: The Map is Not the Territory

The narrative fallacy in the Land of Make-Believe.

What is it that sets humans apart from other animals?

It’s a question I have pondered often and in a variety of contexts. Among my (necessarily) tentative answers is that we humans have the unique capacity to imagine the world as it isn’t, but as it might be, allowing us to work to turn such visions into reality.

We use narrative to make sense of those visions.

The visions, which usually take narrative form, are far more numerous than there have been humans in the history of this terrestrial ball, but many of them focus on our innate desire to matter. We are inveterate meaning-makers through-and-through. We all want to be heroes within our own stories. We want to save the day, our loved ones, and ourselves.

This week’s TBL will have a look at that process. If you like The Better Letter, please subscribe, share it, and forward it widely.

Thanks for reading.

Land of Make-Believe

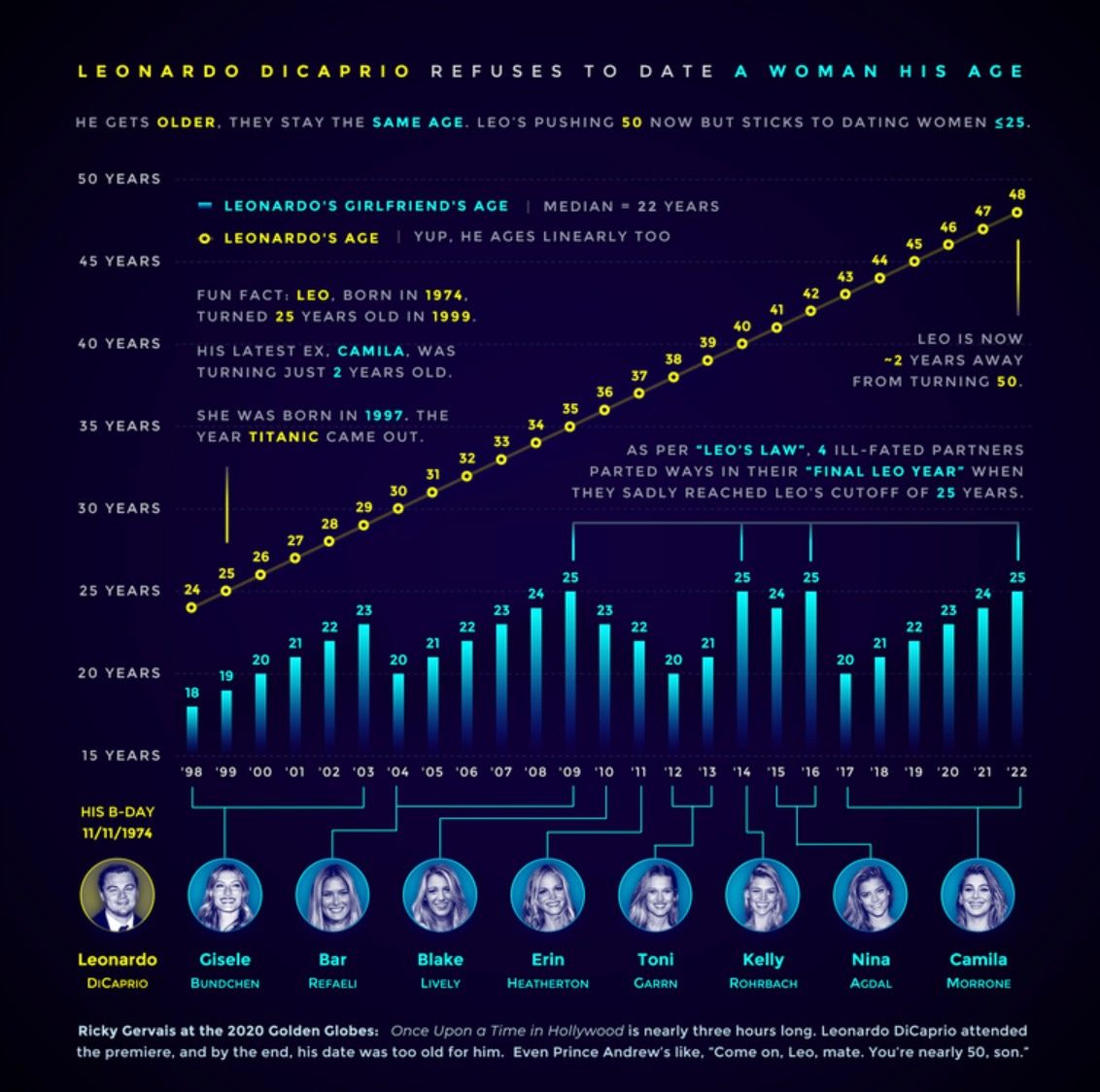

Following Leonardo DiCaprio’s recent breakup with longtime girlfriend Camila Morrone, who turned 25 in June (the same age as Leo’s breakout hit movie, Titanic), the widely circulated hypothesis that the 47-year-old, never-been-married actor refuses to date women over the age of 25 seems to have been established, the correlation/causation question notwithstanding.

Leo is hardly the first middle-aged man to date much younger women, nor is he the first to do so in a continuous pattern. He’s simply the only one that’s been graphed. Rich and famous people from Harrison Ford to Jerry Seinfeld to Donald Trump to Mick Jaggar to Johnny Depp have carried out flings, dated, and even married women decades their junior.

My less-than-scientific survey of middle-aged men suggests that more would try it if they were rich enough to get away with it.

Why do men generally find younger women more desirable than older women?

Evolutionary psychologists tell us that younger women are more likely to be fertile and healthy, and their progeny are thus more likely to arrive and survive. Accordingly, per this thinking, male preferences are driven by genetics, through the mechanism of evolution by natural selection during the Pleistocene era, to optimize the chances of their genes being preserved.

This claim has a certain plausible elegance to it. It may even be true, despite its consistency with common stereotypes. It's a story that seems too good not to be true.

However, despite the scientific imprimatur with which it is offered, it is — nonetheless — a just-so story, without empirical evidence to support it. The interior lives of our progenitors left no fossil record. As Stephen Jay Gould recognized, linking the behavior of humans to their evolutionary past is fraught with peril, “not least because of the difficulty of disentangling culture and biology.”

Because of the narrative fallacy, we insist on plunging ahead anyway. Even scientists. Especially scientists, at least sometimes.

The narrative fallacy is our general inability to look at sequences of facts or events without weaving an explanation into and around them. Explanations bind facts together in our minds and memories. The fallacy part, as the semanticist Alfred Korzybski reminded us, is that “[t]he map is not the territory.” Korzybski emphasized that symbols (“maps”) are not the things symbolized (the “territory”). “Those who rule the symbols, rule us.”

The opening line of Ursula K. Le Guin’s science fiction classic, The Left Hand of Darkness, brilliantly makes the point: “I’ll make my report as if I told a story, for I was taught as a child on my homeworld that Truth is a matter of the imagination.” Obviously, her “homeworld” is more like ours than we care to admit.

Using better words – telling a better story – can change everything.

Truth is beside the point. With good stories, we’re “easy to convince.”

We are susceptible to good stories; we want to be entertained.

As his handler Fuches reminds contract killer Barry in the HBO series of the same name, the real-life William Wallace didn’t give that iconic speech we watched and remember in Braveheart.

People, he said, “don’t want honest. They want entertainment.” As Fuches repeatedly insists, “I guess everyone’s a hero of their own story, right?” Series star Bill Hader notes, “They want to see the thing that they’re not.”

Even Erasmus recognized that most will learn nothing from a sermon but remember a good story told by the preacher.

The artistic impulse, (in a bit of delicious irony, this idea is often falsely attributed to Mark Twain), is never to let the facts get in the way of a good story. Significantly, Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton is consistently wise to this problem in that the characters (and George Washington especially) are aware that who tells the story is crucial to how one is perceived and remembered.

We love stories, true or not, from cradle to grave. We all trade them and try to control our narratives. Stories are crucial (as “maps”) to how we make sense of reality (the “territory”). They help us to explain, understand, and interpret the world around us. Stories take us to a land of make-believe, both figuratively and literally.

Stories give us a frame of reference to remember the concepts we take them to represent. Whether measured by my grandchildren begging for one (or “just one more”), television commercials, the book industry, data visualization, series television, journalism (which reports “stories”), the movies, the parables of Jesus, video games, cable news opinion shows, or even country music, story is perhaps the overarching human experience. It is how we think and respond.

Narratives need heroes, villains, character arcs, redemption, vindication, and meaning, all of which can overshadow or obscure what is unequivocally real, like facts and data.

Whether we like it or not, stories are powerful. An oft-cited Ohio State study found that a message in story form is up to 22 times more memorable than disconnected facts alone. The Significant Objects Project allowed researchers to sell worthless baubles on eBay for surprising amounts when they linked each one with a compelling story.

We are hardwired to respond to story such that a good story doesn’t feel like a story – it feels exactly like real life, but is most decidedly not real life. It is heightened, simplified, and edited. We prefer rhetorical grace and an emotional charge to precise linearity and the work of hard thought. Because we are constant simplifiers, we prefer a clean and clear narrative to a complex reality.

Released nearly 25 years ago, Peter Weir’s brilliant film, The Truman Show, may be the work of art that best anticipated the essence of the 21st century. It stars Jim Carrey as Truman Burbank, adopted and raised by a corporation inside and enclosed by a reality television show of his life, until he discovers the charade and decides to escape. A taut, dark, yet funny masterpiece whose prescience only deepens with time, Truman’s entire existence from the womb has been televised, and all the people in his life have been paid actors.

The show’s creator and director, Christof (played by Ed Harris), was a prophet when he proclaimed that, “We’re tired of actors giving us phony emotions … [“The Truman Show”] is not always Shakespeare, but it is real.” Or as real as most Instagram accounts, anyway.

As he discovers the truth about his existence, Truman fights to find an escape – through a door that looks like the sky – from those who have always controlled him and his simplified and utterly phony reality. He wants to leave the map and live in the territory.

When the film began showing in theatres, people doubted that anyone would watch Truman’s banal life. Today, few doubt that many would choose to be Truman. In any event, real live people today believe they are living in a reality show. They suffer from The Truman Show Delusion.

Like Truman, we all struggle with the narratives we seem to have been given. We are all, as Devorah Goldman argued, balancing our roles as “creator and created, limited by circumstances and nature but bent on inventing ourselves and managing how we are perceived.” As Christof explained, “We accept the reality of the world with which we are presented. It’s as simple as that.”

As I often say, we like to think that we are like judges, that we carefully gather and evaluate facts and data before coming to an objective and well-founded conclusion. Instead, we are much more like lawyers, grasping for any scrap of purported evidence we can exploit to support our preconceived notions and allegiances. Doing so is a common cognitive shortcut such that “truthiness” – “truth that comes from the gut” per Stephen Colbert (the video can’t be embedded; watch it here) – seems more useful than actual, verifiable fact. What really matters is that which “seems like truth – the truth we want to exist.” That’s because, as Colbert explained, “the facts can change, but my opinion will never change, no matter what the facts are.”

As ever, we see the truthiness in others and are blind to it in ourselves.

We think of our brains as linear processors of information. They aren’t. We are always wondering how the information we’re receiving fits together. Our stories provide coherence and overarching meaning, the basis for creating the desired connections. Accuracy is only an occasional by-product.

Reality is messy. Stories? Not so much.

Stories need to stand out or they wouldn’t resonate. There needs to be narrative arc or we won’t stick around. Our lives are ordinary and we want to experience the extraordinary, to imagine being extraordinary. Our conversations don’t sound like movie dialogue very often. If characters in a story are too real, too true, it wouldn’t be a very good story.

And we all love a good story.

Totally Worth It

C.S. Lewis, J.K. Rowling, and J.R.R. Tolkien have created worlds where good conquers evil within an ordered universe. Taken together, they have sold something like 600 million copies of their books, far more than any other literature. Movie adaptations of their works constitute 14 of the top 100 grossing films of all-time. Hollywood and New York City may be as blue as the Pacific Ocean, but the movie and the publishing industries recognize what’s true and what sells (if not necessarily in that order). We need and desperately desire heroes. Like soldiers liberating oppressed peoples or cops pursuing justice. And we believe (or should believe) that dedicated groups of “just folks” – of the sort featured in those stories, albeit in the form of talking beasts, wizards, dwarves, and hobbits – are the best way to change the world. For good.

Feel free to contact me via rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or on Twitter (@rpseawright) and let me know what you like, what you don’t like, what you’d like to see changed, and what you’d add. Praise, condemnation, and feedback are always welcome.

This is the best thing I read this week; the best thing I saw. The most stirring. The most powerful. The most interesting. The most impressive. The most fascinating. 700. A lower volatility life. Largely sensible. Also sensible. Legislative overreach. More authoritarianism. We need to laugh. A particular sort of stupidity, explained. Terrifying, especially this time of year. The Ig Nobels. Inside Baseball. Elementary school artist. Art thievery. There is an amazing story to be written about this.

Don’t forget to subscribe and share TBL. Please.

Of course, the easiest way to share TBL is simply to forward it to a few dozen of your closest friends.

Please send me your nominees for this space to rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or via Twitter (@rpseawright).

“Never before in history have new [music] tracks attained hit status while generating so little cultural impact.”

The TBL Spotify playlist now includes more than 225 songs and about 16 hours of great music. I urge you to listen in, sing along, and turn up the volume.

Benediction

Rich Mullins, who died 25 years ago last week, provides this week’s benediction.

Amen.

Thanks for reading.

Issue 123 (September 30, 2022)