On the walls of the city hall of Gouda in the Netherlands is written the Latin motto: Audite et alteram partem (Listen even to the other side). It’s an admonition honored mainly in the breach.

To begin with, we don’t listen all that well very often. We’re too busy thinking about what we’re going to say next.

And when it’s one of them who’s speaking? Ugh.

In today’s polarized climate, we can go from zero to outrage in a heartbeat. It’s well-known and established by this point that you (we) are social media’s product. Our time, attention, and engagement are how we make Alphabet, Meta (ridiculous name, I know), and their ilk far richer still.

A Yale study found that moral outrage is the best way to get “likes” and “shares” on social media. Moral outrage makes Mark Zuckerberg richer. As the former CEO of Google, Eric Schmidt, conceded, “Corporations, at least in social media land, are optimizing, maximizing revenue. You maximize revenue, you maximize engagement. To maximize engagement, you maximize outrage.”

The Bible states it well.

“It only takes a spark, remember, to set off a forest fire. A careless or wrongly placed word out of your mouth can do that. By our speech we can ruin the world, turn harmony to chaos, throw mud on a reputation, send the whole world up in smoke and go up in smoke with it, smoke right from the pit of hell.”

Sounds like Twitter – especially the “pit of hell” part – right?

This week’s TBL suggests a different approach.

When somebody says something that sets you off, or is simply wrong (by your lights), before you dismiss the strawman, pile on the ad hominems, high-fiving yourself for the witty comeback along the way, take a second to consider the idea fairly on its own terms. Consider how your biases and heuristics may impact your perception. Read enough psychology and cognitive science to figure out why your claim might kind of inspire hysterical laughter from people even a little familiar with the field. Don’t rearrange your priors and prejudices and call it thinking.

We might be the result and the construct of eons of evolution. But so is your dog. And he eats dirt. And his vomit.

It’s almost unbelievably easy to find examples of poor decision-making, just plain stupid, or even evil. Especially on Twitter.

But if your examples are overwhelmingly from “them” and not from “us,” you’re in trouble. And you’ve established, for the umpteenth time, that bias blindness is a thing. A ginormous thing, in fact.

As per the scientific method (see last week’s TBL), we should always hold our views of the truth lightly and tentatively, subject to more and better information and arguments. Changing our minds for those reasons (as opposed to mere expediency) is a good, useful, and desirable thing. As Jeff Bezos of Amazon insightfully expressed it, people who are right a lot of the time are people who change their minds a lot.

That’s a lot easier said than done, of course. The ability to change one’s mind calls for a particular mindset to start. Let’s have a look.

This is the fourth TBL in my series on making behavior finance practical. The first three are linked below.

Part Two: The Misinformation Milieu

If you like The Better Letter, please subscribe, share it, and forward it widely.

Thanks for reading.

The Mindset

How often do you think somebody has changed his or her mind due to a Tweet?

I don’t think I’ve seen it, either.

“For desired conclusions,” Thomas Gilovich explained, “it is as if we ask ourselves ‘Can I believe this?’, but for unpalatable conclusions we ask, ‘Must I believe this?’” With the former, we’re seeking permission to believe, and accept any remotely plausible scrap of support, sometimes less. With the latter, we’re looking for an escape route. Which we can’t wait to use.

That reality provides a very good explanation for why people change their minds so seldom that the claim it never happens — especially about things we care about — is only modest hyperbole. Or, as Daniel Kahneman says, “to a first approximation.”

Some think (perhaps ironically, but I think tellingly) that mindsets conducive to changing one’s mind are pretty much the mindsets needed to be a good person.

We can choose how we want to look at things. We can choose our attitudes. We can choose to question our priors. Not perfectly, of course. But what a wonderful (and wonderfully subversive) opportunity.

Most of us want to change the world. That’s generally a good thing. Dreaming big starts with acting small. If you want to change the world, you must start at home.

But when Thomas Jefferson claimed that “we are not afraid to follow truth wherever it may lead, nor to tolerate any error so long as reason is left free to combat it,” he was speaking aspirationally more than descriptively. Tolstoy got it right: “Everyone thinks of changing the world, but no one thinks of changing himself.”

The most important person you’ll ever coach is yourself. Here are mindsets that matter. Foster these.

1. Integrity. Every elementary school teacher hears from parents astounded that their child lies. They usually ask something like, “Where did he learn to lie?” However, we all lie naturally. We need to learn to tell the truth. Integrity goes even further and is even harder. It demands we do the right thing all the time. Every time. Doing so requires careful and consistent consideration of what is right and true.

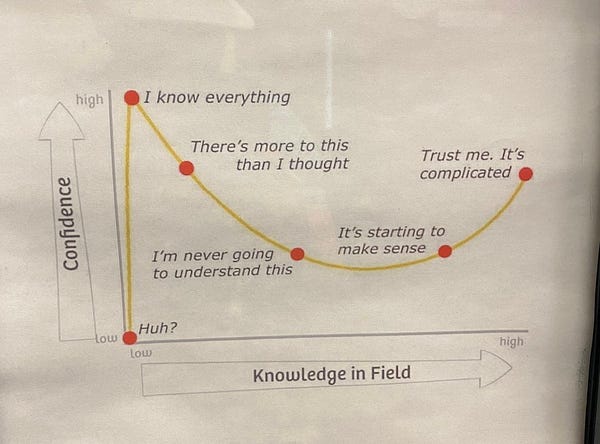

2. Curiosity.

3. Empathy. If we are empathetic towards others – putting ourselves in their place – we’ll be much more open to the idea that they were right all along. Or partly right. Or not altogether wrong. Or not crazy. It will also inspire us to listen to them. And maybe even befriend them. Then, we may not agree with them, but we aren’t likely to hate them. That’s a start.

4. Humility. Humility – intellectual and otherwise – is a superpower. It protects us from ourselves and our (all too human) insistence that we’re always right. As Shakespeare would have it, “The fool doth think he is wise, but the wise man knows himself to be a fool.”

5. Skepticism. Skepticism is the scientific mindset. It requires always being open to new or additional evidence and arguments. It requires checking things out. Checking the math. Checking the results. Checking ourselves. Again. And again.

6. Kindness. We usually think of kindness as how we treat others. But it is an epistemic virtue, too. Sadly, most of us care more about being right than being kind, even (especially!) when we’re wrong. Epistemic kindness is related to humility. We should be kinder to ideas we disagree with. This sort of kindness attacks our inherent arrogance. Truth is more important than self-glorification, especially when there’s a lot at stake. As my favorite preacher likes to say, “when in doubt, give them grace.”

Totally Worth It

Feel free to contact me via rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or on Twitter (@rpseawright) and let me know what you like, what you don’t like, what you’d like to see changed, and what you’d add. Praise, condemnation, and feedback are always welcome.

“Consumers particular[ly] vulnerable to financial bulls*** are more likely to be young, male, have a higher income, and be overconfident with regards to their own financial knowledge.”

Don’t forget to subscribe and share TBL. Please.

Of course, the easiest way to share TBL is simply to forward it to a few dozen of your closest friends.

This is the best thing I read this week. The craziest (I know it isn’t fresh). The prettiest. The smartest. The sweetest. The loveliest. The dirtiest. The funniest, unless it’s this. The best thread. An excellent thread. The best mitzvah. The best advice. The best presentation. The most disappointing, unless it was this. The most dangerous. The most insane. The most important. The most infuriating. The most insightful. The most powerful. The most sickening. The most heart-warming. The least surprising, unless it was this. There are seven types of stupid, examples here and here. Shot; chaser. Bureaucracy. Chow time. Truly awful. Sharks. Snarky but true.

Please send me your nominees for this space to rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or via Twitter (@rpseawright).

The TBL Spotify playlist now includes more than 200 songs and about 15 hours of great music. I urge you to listen in, sing along, and turn the volume up.

Benediction

We could all use some Holy Ghost Fire.

This week’s benediction is a poem.

Within Christianity, the feast of the Visitation usually falls on the 31st of May (this past Tuesday). It celebrates the lovely moment in Luke’s Gospel (1:41-56) when Mary goes to visit her cousin Elizabeth, who was also, against all expectations, bearing a child, the child who would be John the Baptist. Luke tells us that the Holy Spirit came upon them, and that the babe in Elizabeth’s womb “leaped for joy” when he heard Mary speak. Mary gives voice to her Magnificat, the most beautiful and revolutionary hymn in the world.

The Visitation (listen to the poet, Malcolm Guite, read it aloud, here).

Here is a meeting made of hidden joys | Of lightenings cloistered in a narrow place | From quiet hearts the sudden flame of praise | And in the womb the quickening kick of grace.

Two women on the very edge of things | Unnoticed and unknown to men of power | But in their flesh the hidden Spirit sings | And in their lives the buds of blessing flower.

And Mary stands with all we call ‘too young’, | Elizabeth with all called ‘past their prime’ | They sing today for all the great unsung | Women who turned eternity to time | Favored of heaven, outcast on the earth | Prophets who bring the best in us to birth.

For me, the beginning of June points toward a summer’s visitations – visitations of a different sort – filled with the joys of a wonderful wife, children, grandchildren, a lake, and time. May such joys abound to all of you, too.

Amen.

Thanks for reading.

Issue 116 (June 3, 2022)