When I was a student at Duke, Waffle House restaurants (I use the term “restaurants” loosely) were ubiquitous along the interstates of North Carolina and elsewhere in the South. Their yellow-and-black signs haven’t changed in the 40+ years since, and their laminated menus with color photos are an intentional throwback to the heyday of the highway diner. Comedian Jim Gaffigan jokes that the Waffle House “makes the IHOP seem international.”

The Waffle House Index is an informal metric used by the Federal Emergency Management Agency to understand the impact of a severe storm and the likely scale of assistance required for disaster recovery. The standard is based upon the reputation of the restaurant chain for staying open during extreme weather and for reopening quickly, even if with only a limited menu, after very severe weather events.

The company fully embraced its post-disaster business strategy after Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Seven of its restaurants were destroyed and 100 more shut down, but those that reopened quickly were swamped with customers and generated a lot of goodwill.

The index was created by FEMA Administrator Craig Fugate in May 2011, following a major tornado in Joplin, Missouri. At that time, the two Waffle House restaurants in Joplin remained open despite the EF5 multiple-vortex tornado. According to Fugate, “If you get there and the Waffle House is closed? That’s really bad. That’s where you go to work.”

The Index has three levels, based on the extent of operations and service at the restaurant following a storm.

Green: the restaurant is serving a full menu, indicating the restaurant has power and damage is limited.

Yellow: the restaurant is serving a limited menu, indicating there may be no power or only power from a generator or food supplies may be low.

Red: the restaurant is closed, indicating severe damage.

The VIX — which is the trademarked ticker symbol for the Chicago Board Options Exchange Market Volatility Index — is a popular measure of the implied volatility of S&P 500 index options and, for many, operates something like the Waffle House Index for the markets. It is often referred to as the “fear index” and it represents a key measure of Mr. Market’s expectation of stock market volatility over the next 30 days. Something like the VIX was first envisioned by academics in 1989.

Another such indictor is the relative flatness or steepness of the yield curve, which is often used to forecast future economic growth.

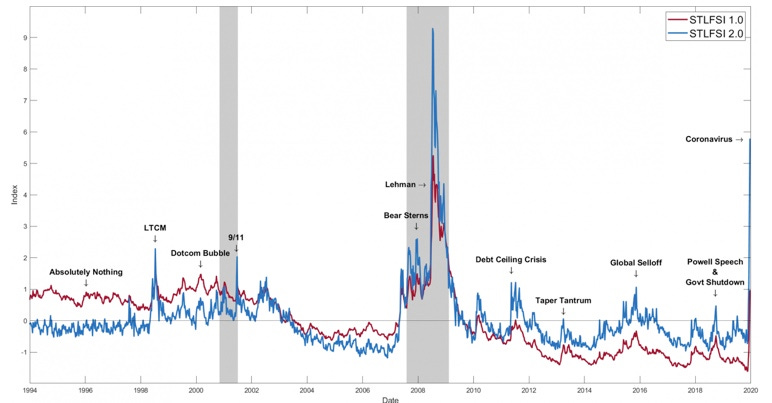

In 2010, the St. Louis Fed created the financial market stress index to attempts to measure financial market stress by combining many indicators into a single index number. It used 18 distinct measures of financial stress – 7 interest rates, 6 yield spreads, and 5 other indicators – to try to measure overall stress. A value above 0 indicated higher-than-average levels of financial market stress, while values below 0 indicated lower-than-average levels of stress. This index was reconstituted last year to try to improve its effectiveness (the old one wasn't sufficiently stressed out – see below).

Only time will tell how effective this measure is. The public would surely benefit from simple red, yellow, and green indicators to estimate market (or life) risk, no matter how likely it is.

Risk is the theme of this week’s TBL.

If you like The Better Letter, please subscribe, share it, and forward it widely. It’s free, there are no ads, and I never sell or give away email addresses.

Thank you for reading.

Risk-Aware

My family likes to play cornhole. Two of my grandsons were playing recently with some minor adjustments. They changed the rules and the scoring system to award extra points for scores while throwing overhand or via a hook shot. One of Aiden’s overhand offerings smacked Ben, who wasn’t paying appropriate attention, in the face. When Ben got nailed again, albeit not in the face this time, Aiden was warned that if it happened again, he wouldn’t get to play cornhole for a week.

It happened again and Aiden got the promised punishment.

Ultimately, Aiden wasn’t sufficiently risk-aware. He underestimated the likelihood that he wasn’t as good with a beanbag as he thought, especially in relation to the stiffness of the penalty.

Far, far more tragically, the Surfside catastrophe seems to fall into this category.

Risk is an elusive concept. It is anything but tame, benign, entirely predictable, or fully controllable. It takes on different guises in different situations or contexts and is not susceptible to precise definition.

We all need to reckon with risk. We need to study it, try to quantify it, and analyze it.

A logical starting point for reckoning with risk is Frank Knight’s classic distinction between risk and uncertainty. Risk has an unknown outcome, but we know what the underlying outcome distribution looks like. Think poker. Uncertainty also implies an unknown outcome, but we can’t know what the underlying distribution looks like. War is uncertain. Knight argued that objective probability is the basis for risk (we can know the exact likelihood of drawing an inside straight), while subjective probability underlies uncertainty (we can’t know how war will turn out, or how older Florida high-rise condominium values will shake out).

In the probabilistic sphere, where risk isn’t necessarily bad or good, we have a number of issues to work through. Because of my day job, I tend to think of risk in the context of investing, but it obviously applies much more broadly. Here are some of those issues.

1. As with Katniss in The Hunger Games, may the odds be ever in your favor. If you are likely to lose, you shouldn’t play. Of course, “losing” and “winning” have broader meanings in this context than people typically assume. For example, if I lose $10 and the bet 60 percent of the time but win $20 40 percent of the time, that’s a winning bet overall (which leads directly to #2).

2. Size matters. As in poker, the size of your bets should relate to both the likelihood of winning and the stakes. Pocket aces are worth a significant investment; a two and a three are not (unless you’re bluffing, which is outside the scope of a discussion of investing – trading is another matter). In On the Waterfront, Marlon Brando as the boxer Terry Malloy offers his famous lament.

Had he not taken the sure-thing “short-end” money – a relative pittance – to throw the fight, his upside potential was enormous, he “coulda been another Billy Conn.”

3. The markets can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent (a saying often falsely attributed to Keynes). Because of general randomness, even when the odds are in your favor, you need a lot of bets to have reasonable confidence that things will pan out as expected. Phrases like “small sample size” explain why a bet can make great sense but still not work out.

4. Avoid “déjà vu all over again.” When your goal is many different kinds of bets for diversification purposes, you need to make sure you’re not essentially making the same bet over and over. That’s the 2008 problem writ large. What were presumed to be different bets then weren’t so different after all. That’s a recipe for getting rolled when the market turns against you.

5. Be extra careful “where the wild things are.” Most economic models assume a “mild randomness” of market fluctuations. However, and especially at the extremes, what visionary mathematician Benoît Mandelbrot called “wild randomness” prevails. Risk tends to be concentrated in a few rare, hard-to-predict, but extreme, events.

6. The world seems more regular and predictable than it is. As G.K. Chesterton wrote: “The real trouble with this world of ours is not that it is an unreasonable world, nor even that it is a reasonable one. The commonest kind of trouble is that it is nearly reasonable, but not quite. Life is not an illogicality; yet it is a trap for logicians. It looks just a little more mathematical and regular than it is; its exactitude is obvious, but its inexactitude is hidden; its wildness lies in wait.”

7. Once you have won, stop playing. When you have already won the game, why risk damage and perhaps screwing up everything you’ve accomplished? When you have met your goal(s), it’s time not just to take risk off the table but to get out of the game entirely.

Risk analysis essentially boils down to a set of fairly straightforward considerations overall, even if and as it remains maddeningly difficult to deal with and impossible to control. When reckoning with risk, begin by being risk-aware and considering the following.

· What can go wrong and why.

· How much being wrong (or right) matters.

· What (if anything) can be done about it.

· The relative risks and uncertainties of playing, winning, and losing.

· How much being wrong (or right) costs.

Despite what many salespeople in my industry would have people believe, every investment entails risk. Everything in life has risks attached. Risk and reward are inherently connected.

Risk is always risky.

A Little Off

Something seems a little off in the markets. Perhaps it is several somethings, where bad is good somehow.

All year, amateur investors, propelled by a social media frenzy and more than a bit of boredom, have poured money into highly speculative “investments” like so-called meme stocks and cryptocurrencies. The cryptos have taken a beating of late but meme stocks have largely continued to perform. For example (as of yesterday), AMC Entertainment remains not too far from its record high and is +2,161 percent in 2021 while GameStop's stock price remains close to $200 (+916% YTD) a full five months after it peaked at nearly $400 amid an epic short-squeeze.

Indeed, you would have done far, far better owning Dogecoin this year (+4,114%, as of yesterday, YTD; it may be wildly different today) than Pfizer (+8.75%), Moderna (+123%), or JNJ (+8.75%). The former is (literally) a joke; all the latter three did was create effective vaccines in record time during a pandemic to save millions of lives and allow global economies to re-open.

Bloomberg notes that since March, almost 100 money-losing companies have raised money via secondary offerings, twice the number of profitable companies. According to Sundial Research, over the past 12 months, 750 unprofitable companies have turned to the secondary market. That’s the widest margin between money-making and money-losing firms in nearly 40 years.

Junk bonds are now yielding just over 4 percent. That’s an all-time low. In fact, the spread between junk and investment-grade debt is the narrowest it’s been in over a decade.

MicroStrategy Inc. is a profitable but not particularly large enterprise analytics software company. As Matt Levine and others have reported, The firm seems to have decided that enterprise analytics software, while profitable, is boring and that it would be more fun to speculate in cryptocurrency markets (really). MicroStrategy went to its shareholders — and convertible bond investors, and even high yield bond investors — and said (paraphrasing): “If we wanted to speculate wildly on cryptocurrency, would you fund that?” I don’t know whether I should be surprised about it or not, but the investors were like, “Absolutely.”

The consensus view seems to be that the economy is in good shape, the disruptions caused by the pandemic are working themselves out, and the inflation we’re seeing is explicable via non-worrisome (“transitory”) mechanisms. Today’s financial stress level is very low (see below), supporting the consensus view.

However, with the obvious caution that anecdotes aren’t data, stories like these force me to be a bit nervous about the consensus. One way to look at risk is that more things can happen than do happen, and what the consensus thinks will happen is not always what happens. We humans are dreadful at forecasting.

Back in the day, when I worked on a huge trading floor and pondered these sorts of things every day, I was always careful to consider what trade(s) hurt the most people. Maybe the consensus is a trap.

Color me concerned.

Totally Worth It

We each have 525,600 minutes per year to use wisely, well, or foolishly.

This is the best thing I saw or read this week. This (more here) is the most powerful. The worst. The least surprising. The most interesting. The most insightful. The funniest (unless it was this). The most sensible. The saddest. The sweetest. The smartest. The best apologetic. The most bi-partisan.

Be sure to read this essay from Arthur Brooks on patriotism, nationalism, and happiness.

An interesting piece in The New York Times noted that “analysis by Gallup found that the share of white Democrats who identify as liberal had risen by 20 percentage points since the early 2000s. Over the same period, the polling firm found a nine-point rise in liberal identification among Latino Democrats and an eight-point increase among Black Democrats.” Accordingly, white progressives are increasingly out-of-step with voters of color on the exact issues they think they are speaking most directly for those voters: those concerning race. As reporter Lisa Lerer wrote, “as liberal activists orient their policies to combat white supremacy and call for racial justice, progressives are finding that many voters of color seem to think about the issues quite a bit differently.”

Please contact me via rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or on Twitter (@rpseawright) and let me know what you like, what you don’t like, what you’d like to see changed, and what you’d add. Don’t forget to subscribe and share.

Of course, the easiest way to share TBL is simply to forward it to a few dozen of your closest friends.

Benediction

I have written before about Jane Marczewski, known professionally as Nightbirde, an American singer and songwriter who recently won a “golden buzzer” from Simon Cowell on America’s Got Talent while battling cancer. Her powerful writing about dealing with her cancer included the following.

“I have had cancer three times now, and I have barely passed thirty. There are times when I wonder what I must have done to deserve such a story. I fear sometimes that when I die and meet with God, that He will say I disappointed Him, or offended Him, or failed Him. Maybe He’ll say I just never learned the lesson, or that I wasn’t grateful enough.”

Some read those lines and blame religion for allowing someone like this remarkable young woman to believe that her body being ruined by cancer is somehow her fault.

Followers of religion in general and Christianity, in particular, have done a grave disservice to many hurting and broken people by giving them reason to think their particular sins – and we all have many – cause disease or other misfortune. Our decisions have consequences, of course, but that is hardly reason to think that God causes evil.

Note how Sam Allberry, a pastor, gets to the issue.

“We don't live in a moralistic age where we need to prove people to be sinners. We live in an anxious age where we need to prove to people they're worth something.”

As this week’s benediction proclaims, “Our sins they are many. His mercy is more.”

Thanks for reading.

Issue 70 (July 9, 2021)

Thanks especially for those words from Sam Allberry - much needed!