The best gifts of Christmas offer more than what we can hold in our hands.

If you like The Better Letter, please subscribe, share it, and forward it widely. It’s free!

Thank you for reading.

Insufficient Imagination

In Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Sign of the Four, Holmes and Watson are confronted with what appears to be an impossible burglary. Somehow, a criminal entered a room high above the ground without using any doors or windows. Watson is preoccupied with the seeming impossibility of the feat but Holmes questions Watson’s conception of what’s possible and utters one of the most famous lines of the Sherlock Holmes canon.

“You will not apply my precept,” he said, shaking his head. “How often have I said to you that when you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth? We know that he did not come through the door, the window, or the chimney. We also know that he could not have been concealed in the room, as there is no concealment possible. Whence, then, did he come?”

The phrase is sufficiently famous that it now extends well beyond Sherlock.

The idea is an elegant summation of Holmes’ approach and of science in general. The scientific method is the procedure that has characterized scientific inquiry since the 17th century, consisting of systematic observation, measurement and experiment, and the formulation, testing, and modification of hypotheses. It is about making observations and then asking pertinent questions about those observations. What it means is that we observe and investigate the world and build our knowledge base on account of what we learn and discover, but we check our work at every point and keep checking our work, even after we’ve reached a (necessarily tentative) conclusion.

Aristotle posited that heavy objects fall faster than lighter objects and that males and females have different numbers of teeth, based upon some careful – though flawed – reasoning. Yet it never seems to have occurred to him that he ought to check before presuming he was right. Science, via Galileo, corrected that error with respect to gravity. Looking in mouths and counting corrected the mathematical error.

In its broadest context, science is the careful, systematic, and logical search for knowledge, obtained by examination of the best available evidence, and always subject to correction and improvement upon the discovery of better or additional evidence. This construction can and should be applied not only to traditional scientific endeavors but, also, to the fullest extent possible, to any sort of inquiry about the nature of reality.

Sherlock Holmes demonstrates this point constantly. He follows the evidence wherever it leads – even when it leads to a seemingly improbable place.

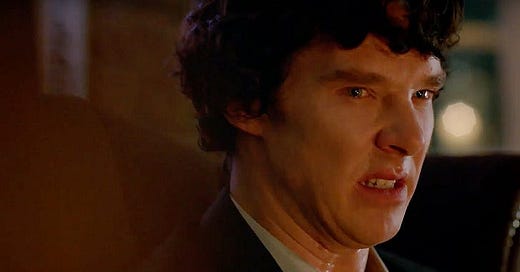

In the BBC’s typically brilliant cinematic reimagining of the Holmes lexicon, an altered version of this concept appears in a disappointing episode based upon The Hound of the Baskervilles, the most venerable of the Doyle mysteries featuring the inimitable detective. It is set on a bleak moor in England’s West Country and tells the story of a murder inspired by the legend of a fearsome, diabolical hound of alleged supernatural origin, an origin story Holmes cannot easily countenance.

“Once you have ruled out the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be true,” says this Sherlock.

Here, Holmes utters the line as he raves, in a drug-induced delirium, about the enormous, red-eyed hound he is certain he saw. In this context, the elegance of the original idea is stripped away. All Sherlock seems to mean by it is, “I know what I saw!”

Significantly, Holmes fails to “exhaust the hypothesis space.” Holmes is far too certain of his ability to marshal all the possibilities. The number of possible hypotheses will almost surely exceed the imagination of one inherently limited thinker, even one as gifted as Sherlock Holmes. Even Aristotle. The “highly improbable” is indeed possible, but less likely than an unconsidered hypothesis. Each of us is limited by a lack of knowledge, a lack of imagination, and bias.

The “sherlocking” example in the clip immediately above (following the money quote), whereby the detective creates an entire explanatory narrative from a few careful observations – offered by Holmes to show that “There is nothing wrong with me, do you understand?!” – demonstrates the point.

Holmes posits a plausible narrative, to be sure, but there are others. Perhaps the woman is a mark and the man, an out-of-work fisherman who has turned to larceny, wears the Christmas “jumper” to inspire trust because she loves the season. Perhaps the man is trying to seduce the older woman to marry her for her money. Perhaps the man has lost a bet to the woman and is forced to pay for a dinner he cannot really afford while wearing an ugly Christmas sweater to make good on it. Perhaps the man is trying to lose some weight. I’m sure you can come up with others.

Holmes’ plausible scenario isn’t ordained. The implausible happens all the time.

Most notably, it never seems to have occurred to Holmes that he ought to check before presuming he was right. That’s hardly good scientific practice.

The problem is exacerbated by Sherlock’s obvious conviction, making it that much harder for him to see that and where he might be wrong. Classic research from 1956 makes the point clearly.

“A man with a conviction is a hard man to change. Tell him you disagree and he turns away. Show him facts or figures and he questions your sources. Appeal to logic and he fails to see your point.”

In related news, what we are looking for is highly determinative of what we see. If we don’t know what to look for – Donald Rumsfeld’s famous “unknown unknowns” – we’ll miss a lot without even realizing it. As Jesus said, “It’s easy to see a smudge on your neighbor’s face and be oblivious to the ugly sneer on your own.”

We inhabit a world in which people share cognitive bubbles of the like-minded. They come in two basic flavors. An epistemic bubble is when you don’t hear the other side while an echo chamber is what happens when you don’t trust the other side. In each, the other side is always wrong and perhaps stupid, evil, or mentally ill. Moreover, we suffer a physiological reaction to negative arguments and to negative facts. We feel threats to our worldview.

It reminds me (again) of C.S. Lewis – especially The Great Divorce – and his idea that the damned could leave Hell for Heaven at any time, but mostly don’t, because it would require an admission of error.

It’s hardly a coincidence that seeking ways to see things from the other side’s point of view or working to remain humble and open to correction are crucial both to overcoming bias *and* to becoming a better person. In fact, becoming a better person may well be a precondition for beginning to overcome bias.

SPOILER ALERT: We’re all depraved sinners.

That said, no matter how many times they tell you the dress is blue and black, you will still see gold and white. We quite literally (used correctly for once) can’t agree on what we’re looking at when we’re looking at the exact same thing. It isn’t just the other side. We read the world wrong and say that it deceives us.

That’s why science is so important.

Like Sherlock, we are all prone to thinking we’ve got things all figured out. That tendency (which exists among scientists, too, of course) is a monumental error.

When Jane Curtin was asked if the person she was mimicking for a screen role knew that she was the source material, she replied, “I used to do my aunt when I was doing improv, and she always thought I was doing my other aunt.” Cluelessness is a human staple.

We prick holes in the dark thinking we’re finding, rather than forming, patterns of light. We don’t wait for the evidence to catch-up to (or disconfirm) our priors.

On our best days, when wearing the right sort of spectacles, squinting and tilting our heads just so, we can be observant, efficient, loyal, focused, assertive truth-tellers. However, on many days, all too much of the time, we’re delusional, lazy, short-sighted, partisan, arrogant, easily distracted confabulators. It’s an unfortunate reality, but reality nonetheless.

Note that Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes and the author of many great paeans to rationality, believed in fairies and thought his wife could talk to spirits.

In The Island of Knowledge: The Limits of Science and the Search for Meaning, physicist Marcelo Gleiser recounts the enormous progress of modern science in the pursuit of our most fundamental questions. “What we see of the world,” Gleiser begins (contra Holmes), “is only a sliver of what’s out there.” The universe is more bizarre than we know, more bizarre than we can know.

The Fox said to the Petit Prince in Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s fable, “What is essential is invisible to the eye.” He might be speaking of oxygen. He might be speaking of our shortcomings. He might be speaking of love.

As UCLA paleobiologist William Schopf asked within a commentary on the origins of life, “What do we know? What are the unsolved problems? What have we failed to consider?”

What we know of the world is limited not just by what we can see and describe, but also by what we can imagine, what we have failed to consider. Gleiser offers an apt metaphor for the journey of discovery.

“As the Island of Knowledge grows, so do the shores of our ignorance — the boundary between the known and unknown. Learning more about the world doesn’t lead to a point closer to a final destination — whose existence is nothing but a hopeful assumption anyways — but to more questions and mysteries. The more we know, the more exposed we are to our ignorance, and the more we know to ask.”

If we were to tie a rope tight around the Earth’s equator – about 24,901 miles of rope – and then added just a single yard of slack (additional knowledge), would the extra footage make any noticeable difference to someone standing on the ground nearby?

The astonishing answer, contrary to our intuition, is “Yes.”

The additional three feet of rope across nearly 25,000 miles raises it almost six inches off the ground all around the earth. The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein believed that this gap between our intuition and physical reality reveals something important about our thinking. After all, if something that seems obvious to almost everyone can be totally false, what else might we be wrong about? What else might Aristotle be wrong about? Or Sherlock Holmes?

As it turns out, ever and always, the correct answer to that important question is, “A lot.”

Totally Worth It

Terry Gross interviewed Sir Paul McCartney for NPR recently. Paul describes how, driving through a blizzard, the Beatles’ van slid off the road, down a slope, and turned on its side.

“It was like, well, how are we going to get to Liverpool? And out of that, though, came … one of our greatest sort of mottos. …We’re standing around … and somebody said, ‘Well, what are we going to do now?’ And then one of us — I can’t remember which — said, ‘Something’ll happen.’ … That is, like, the greatest quote ever because in life, when you’re faced with these crazy things, something will happen. And it always seemed to console us. … I’ve told quite a few people since then … that when you’re in your darkest moments, just remember that incredibly intelligent Beatle quote: ‘Something’ll happen.’”

As Russell Moore pointed out in his newsletter yesterday, “‘Something’ll happen’ is not the fullest expression of a biblical view of divine providence, but it’s not really wrong either. So I’ll let it be.”

Feel free to contact me via rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or on Twitter (@rpseawright) and let me know what you like, what you don’t like, what you’d like to see changed, and what you’d add. Don’t forget to subscribe and share.

Of course, the easiest way to share TBL is simply to forward it to a few dozen of your closest friends.

Please send me your nominees for this space to rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or via Twitter (@rpseawright).

This is the flyest thing I saw this week (and it’s amazing).

This is the best thing I saw or read this week. This is also outstanding, but I think the described condition is far more prevalent than the author does. The most sensible. The most interesting. The most misinformed (probably intentionally). The most thought-provoking. The most arresting. The funniest. The silliest. The coolest. The nicest. The best cartoon. Nerd humor. Quebec producers dip into strategic maple syrup reserve after year’s harvest falls short. Common sense. Why workers are quitting their jobs. Uh-oh (one). Uh-oh (two).

The Spotify playlist of TBL music now includes more than 200 songs and 14 and a half hours of great music. I urge you to listen … and turn the volume up. Way up.

Benediction

As Luke’s gospel says, “People will faint from fear and foreboding of what is coming upon the world.” It is true now as then. Advent calls us to look ahead to when that fear and foreboding are finished forever.

To those of us prone to wander, to those who are broken, to those who flee and fight in fear – which is every last lost one of us – there is a faith that offers hope. And may love have the last word. Now and forever. Amen.

Thanks for reading.

Issue 91 (December 3, 2021)

Brilliant, and undeniable on many levels. Thanks for offering a supremely rational ray of hope for the beginning of advent, and a time-worn, tested method of facing the challenges we will all face together in the new year. Personent hodie!