How do you measure a year?

History isn’t likely to measure 2021 and offer a positive report. The enduring lessons seem to be some goulash combining our sense (which may well be true) that everything is broken and our (probably correct) recognition that we’re never quite out of the woods and in the clear. Here’s hoping – praying – that 2022 is better. Much better.

In science, every year, success is measured by predictive power. A valid scientific theory can be applied to predict real phenomena. I will apply that test to a variety of market and other predictions this week in my annual “forecasting follies” report.

Spoiler Alert: They aren’t very scientific (example below).

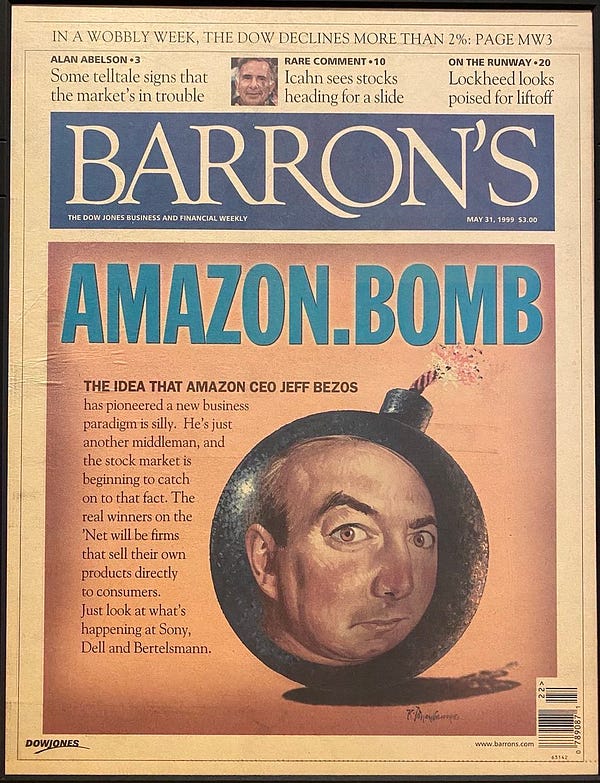

Aside: As Barry Ritholtz pointed out yesterday, perhaps the most overlooked business story of 2021 was Amazon’s poor stock market performance. For the year, Amazon gained just 2.4 percent, far less than its mega-cap competitors: Apple (+34.7%); Tesla (+49.8%); Microsoft (+52.5%); and Google (+65.2%). Gaining only 2.4 percent feels like losing money, especially compared to its peers. And, on an inflation-adjusted basis, Amazon did lose money. As Barry also shows, there are some pretty clear reasons why.

Now, back to our regularly scheduled programming.

If you like The Better Letter, please subscribe, share it, and forward it widely. It’s free, there are no ads, and I never sell or give away email addresses.

Thanks for visiting.

Forecasting Follies 2022

Twenty years ago, in January of 2001, charismatic scientist Dean Kamen, who had made his name (and a lot of money) by inventing the drug infusion pump and the first portable dialysis machine, was secretly developing a new invention in his lab in New Hampshire.

“This is the most exciting thing I’ve ever worked on,” Kamen said.

The invention was being financed in part by a substantial investment from famed venture capitalist John Doerr and his firm, Kleiner Perkins. It was then the largest investment in the firm’s history. Doerr was convinced the invention would become more important than the internet and that Kamen’s company would be the fastest ever to reach $1 billion in revenue. Another investor, Credit Suisse First Boston, called for Kamen’s invention to make more money in its first year than any start-up in history, predicting Kamen will be worth more in five years than Bill Gates.

Steve Jobs wanted to invest $60 million in the project. Kamen turned him down because he didn’t want to lose control.

News of the invention was broken via a leaked, secret book proposal that was sold to the Harvard Business School Press. The proposal quoted Jobs saying the invention would be “as significant as the personal computer. …If enough people see the machine you won’t have to convince them to architect cities around it. It’ll just happen.” Jeff Bezos said the “product [is] so revolutionary, you’ll have no problem selling it.”

Within a few hours, the story was everywhere, even though the invention itself remained under wraps. It was perhaps the first true media frenzy of the internet age and “the birth of virality as we now know it.” Harvard bought the book for big money without knowing what the invention was. Even South Park got in on the act, with an episode that aired November 21.

In December, almost a year after the initial leak, the invention was finally revealed to great fanfare on Good Morning America.

“The Segway,” Kamen intoned proudly.

“That’s it?” Diane Sawyer asked. “That can’t be it.”

That was it.

Kamen thought the Segway could solve the problem of city transportation, especially the “last mile” problem. He thought it could reduce our dependence on fossil fuels and free our cities from the scourge of the automobile. He thought the Segway could change the world.

The business was DOA, but the hype lingered a bit. Time magazine put the Segway on the cover that first week and gave seven pages to the invention. In that story, Kamen predicted the Segway “will be to the car what the car was to the horse and buggy.”

Spoiler Alert: It wasn’t.

Jay Leno rode out on a Segway to do his Tonight Show monologue. Niles rode one on Frasier. G.O.B. Bluth rode one on Arrested Development. And the scooter appeared on the cover of The New Yorker: Osama bin Laden, riding a Segway along a mountain pass in Afghanistan, fleeing coalition forces in style.

As seems obvious now – unless, perhaps, you’re a mall cop – the Segway was a total flop.

Kamen expected to be selling 10,000 units a week by the end of 2002. That's half a million per year. Over the first six years of operation, and then some, Segway moved just 30,000 units. Total.

The company was sold – twice – and production was finally halted in 2020. The second owner of the company rode his Segway off a cliff and died, providing a pretty good (if tragic) metaphor for the entire enterprise. Segway is little more than a punch line today.

“I wouldn't have predicted the mountain would be so big,” Kamen said later. Indeed.

As ever, we humans – even really smart and savvy humans within their areas of expertise – are truly lousy at predicting the future. Still, we keep expecting to be able to. “The idea that the future is unpredictable is undermined every day by the ease with which the past is explained,” Daniel Kahneman wrote in Thinking, Fast and Slow.

As I show every year at about this time, the examples of poor forecasts and predictions are legion.

“If he [Biden] gets in, you will have a depression the likes of which you’ve never seen. Your 401(k)s will go to hell and it’ll be a very, very sad day for this country,” then President Trump said in the October 22 candidate debate. On November 7, 2020, former Trump Chief of Staff Mick Mulvaney published an op-ed in The Wall Street Journal headlined: “If he loses, Trump will concede gracefully.” More recently, “The likelihood there’s going to be the Taliban overrunning everything and owning the whole country is highly unlikely,” said President Joe Biden about Afghanistan. No, no, and no.

Covid-19, which is essentially all uncharted territory, was bound to inspire a host of bad predictions and, of course, it did. Dr. Anthony Fauci, the United States’ leading infectious disease expert, forecast the end of handshakes: “I don’t think we should ever shake hands ever again, to be honest with you.” As the pandemic wore on, experts predicted the end of hugs, offices, cities, office wear, in-store cosmetic samples, co-working, ball pits, and blowing out the candles on a birthday cake. All wrong.

As always, the economy and the markets provide unlimited fodder for bad forecasts.

In late 2020, Barron’s surveyed market strategists and chief investment officers at large banks and money-management firms on their stock market outlooks for 2021. Averaging their year-end S&P 500 forecasts, which ranged from 3800 to 4400, the group expected the index to rise some nine percent last year, to about 4040 (Bloomberg did something similar; its average of 22 estimates was 4,074). JP Morgan was the most optimistic, calling for a 4400 closing level. Goldman Sachs predicted 4300. The S&P 500 closed 2021 at 4766, up nearly 27 percent, before dividends. With dividends, it earned 28.7 percent. Thus, none of these alleged experts was anywhere near right. They missed it by “that much.”

None of this is news. Generally, analysts thought stocks would plunge throughout 2020 after the Covid-19 pandemic hit the U.S. (the S&P 500 gained 18 percent) before badly underestimating the strength of the market’s 2021 rally. Overall, the data is clear: Skeptics sound smart while optimists make money.

Last fall, John Hussman called for a huge market crash. Yet again. He was far from alone as there were many, many more purveyors of doom and gloom. If you had invested in an S&P 500 index fund ten years ago, you would have nearly five-times your initial investment today. If, instead, you had invested in the Hussman Strategic Growth Fund, you would have lost almost half of it and underperformed by more than 20 percentage points per year.

Don’t forget “rich dad, poor dad,” wrong dad, either.

Analysts, economists, and other forecasters are no better at predicting inflation than at predicting anything else: They stink at it. As then-chairman of the Federal Reserve Alan Greenspan understated badly in 1999, estimates of future inflation — including those by the Fed itself — “have been generally off,” and even changes in inflation that were “doggedly forecast” never occurred.

Last year proved the point. Again.

This past April, economists generally thought inflation would be around 2.5 percent right now. Instead, it’s nearly 7 percent. Even by the forgiving standards of economic forecasting, that’s a miss of epic proportions.

In December of 1994, Orange County, California, filed for bankruptcy protection after Robert Citron, its chief investment officer, lost billions of dollars speculating on derivatives and betting that interest rates would not rise. When asked (a year earlier) why his strategy wasn’t risky, Mr. Citron said, “I am one of the largest investors in America. I know these things.”

He didn’t.

Goldman Sachs called Enron “the best of the best” on October 9, 2001. The company (Enron, not Goldman — only very rarely are there consequences for making poor forecasts, even monumentally bad ones) declared bankruptcy less than two months later.

The New York Fed’s monthly Survey of Consumer Expectations reports the public’s expectation as to whether the stock market will be higher in 12 months’ time. Since the survey began in June 2013, the S&P 500 has returned roughly 15.5 percent per year. Over the same period, there has been only one instance where survey found consumers expecting the stock market to be higher in 12 months. That means consumers are wrong – wildly wrong – about where stocks were headed essentially all the time.

As my friend Morgan Housel has explained, “Every forecast takes a number from today and multiplies it by a story about tomorrow.” We might have good current data, but “the story we multiply it by is driven by what you want to believe will happen” and what you’ve decided makes the most sense. Usually, the best story wins, correlation to reality not required.

Kahneman highlighted the “illusion of understanding” – our predisposition to concoct stories from the information we have on hand. “The core of the illusion is that we believe we understand the past, which implies that the future should also be knowable.”

It isn’t.

We miss the shocking “black swan” events, but that’s necessary, even appropriate, because they are, by definition, unforeseeable. But we also miss “dragon-king” events – which, by understanding and monitoring their dynamics, some predictability may be obtained despite their outlier status. We even miss “gray rhino” events, “dangerous, obvious, and highly probable” occurrences that we should see lumbering toward us but usually don’t. Our failures in this regard should encourage us to prepare rather than predict and, perhaps, to try to limit our exposure to extreme fluctuations.

If only.

“No matter how much we may be capable of learning from the past,” Hannah Arendt wrote, “it will not enable us to know the future.”

In April 1980, market guru Joe Granville signaled his 1,500 premium subscribers to buy stocks. The next day, the Dow Jones Industrial Average surged 4 percent to close at 789.85. “I don’t think that I will ever make a serious mistake on the stock market for the rest of my life,” crowed Mr. Granville — who freely admitted he didn’t even invest his own money in stocks. However, Mark Hulbert later calculated that Mr. Granville’s followers lost 98 percent of their money following his advice between 1980 and 1987.

A November 1999 WIRED cover story touted a company called DigiScent, which hoped to launch the next web revolution by sending smells through the internet. The goal: “Reekers, instead of speakers.”

In 1998, the then-future Nobel laureate Paul Krugman made a remarkable and erroneous claim: “By 2005 or so, it will become clear that the Internet’s impact on the economy has been no greater than the fax machine’s.”

Blessed are those who have things all figured out, for boy, will they explain it.

From time immemorial, people have sought to play God, even to be God. We’re terrible at it. As the great polymath Freeman Dyson explained, history is replete with those “who make confident predictions about the future and end up believing their predictions.”

You may be troubled by the vertiginous heights the market reached in 2021 after three straight years of double-digit growth despite a global pandemic, burgeoning inflation, and slowing corporate profits. I am.

You may not be comfortable with current market valuations that remain at nose-bleed heights. Me, too.

You might worry that markets are too dependent upon the Fed’s largesse, huge governmental spending, and at risk going forward. That’s fair.

However, and given the forecasting records of every Wall Street “expert,” those concerns shouldn’t be pointed to as reasons to try to time the market or “go to cash.” One thing I can forecast with virtual certainty: There will be bad times and ugly losses ahead. I just don’t know when.

And neither does anybody else.

If you really could foresee the future, wouldn’t you be working at a hedge fund and making a fortune that way instead of making forecasts and doing media hits?

Because I believe in America and in the American economy – and the global economy, too – I remain invested in stocks and will stay invested in stocks. I could be wrong, of course, but the bias favors growth.

That’s not much of a forecast, but it’s the best I can do. Nobody has a crystal ball.

In scientific terms, it’s the three-body problem applied across a global economy with an infinite number of moving parts.

In mathematical terms, there are far, far too many uncertain, unknown, and unknowable variables to create a decent model (even though, per Ronald Coase, “If you torture the data long enough nature will confess”).

In practical terms, per Kahneman, “The world is incomprehensible. It's not the fault of the pundits. It's the fault of the world. It's just too complicated to predict. It's too complicated, and luck plays an enormously important role.”

In human terms, it’s hopeless. Lots of us will keep trying anyway. So, I’ll have plenty to write about next January.

Happy New Year!

Totally Worth It

When measured by the popular vote, the 1960 presidential election was the closest of the 20th Century. Richard Nixon and the Republican Party were convinced that Illinois’ electoral votes were stolen for John F. Kennedy by the Chicago political machine. They were probably right. Had Illinois officially been in the GOP column, Mr. Nixon would have been elected president. He declined to contest the election, believing it was not good for the country to do so.

In that context, Vice President Richard Nixon stood in the Capitol 61 years ago as the presiding officer to guide the Senate as it formally counted the electoral votes for JFK’s victory. After his duty was done, Mr. Nixon asked to address the Senate. This is what he said. (h/t JVL).

In the current context, and given Mr. Nixon’s subsequent and well-earned reputation for “dirty tricks,” it is both astonishing and impressive.

One year on from insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, we’re still living on a thin line.

Feel free to contact me via rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or on Twitter (@rpseawright) and let me know what you like, what you don’t like, what you’d like to see changed, and what you’d add. Don’t forget to subscribe and share.

Of course, the easiest way to share TBL is simply to forward it to a few dozen of your closest friends.

This is the best thing I saw or read this week. This is pretty great, too. The sweetest. The smartest. The funniest. The coolest. The weirdest. The cringiest. The best thread. 2021’s best headline.

Please send me your nominees for this space to rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or via Twitter (@rpseawright).

The Spotify playlist of TBL music now includes more than 225 songs and about 16 hours of great music. I urge you to listen in, sing along, and turn the volume up.

John Chrysostom: “As long as we remain sheep, we overcome. Even though we may be surrounded by a thousand wolves, we overcome and are victorious. But as soon as we are wolves, we are beaten.”

Benediction

As a New Year begins, this week’s benediction is a virtual choir singing a 19th Century hymn that asks an appropriate question, no matter how bad we think things might be. Please watch the faces of the musicians while you listen.

My life flows on in endless song; Above earth's lamentation, I hear the sweet, though far-off hymn That hails a new creation | Through all the tumult and the strife, I hear that music ringing | It finds an echo in my soul How can I keep from singing?

To those of us prone to wander, to those who are broken, to those who flee and fight in fear – which is every last lost one of us – there is a faith that offers hope. And may love have the last word. Now and forever. Amen.

Thanks for reading.

Issue 96 (January 7, 2022)