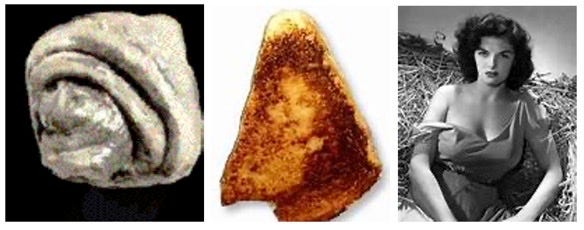

There is no getting around it. We are pattern-seeking generalists. The focus of the image (below left) is a standard issue cinnamon roll, but we easily (eagerly!) see something more, perhaps Mother Teresa.

Really, if God were looking to reveal Himself in this sort of flamboyant, artistic way, don’t you think He would have shown a bit of talent? None of these sorts of examples begin to hold up to da Vinci, Vermeer, or Monet, much less the Grand Canyon or the Northern Lights.

We like to think that we perceive things “as they really are” but, in reality, we often see things as we really are. Our perception is highly ambiguous. We often see what we expect to see, want to see, are primed to see, or are conditioned to see. This general problem is also a function of our tendency to seek excessive detail within complex systems.

My favorite example in this regard is perhaps the famous Virgin Mary grilled cheese sandwich (see above center). Its story is improved dramatically for me in that it was sold for $28,000 back in 2004 to a Las Vegas casino in order to be put on display. That alone is a remarkable commentary on modern American culture. If you aren’t predisposed to see the Virgin, you might think it’s the late actress, Jane Russell (above right).

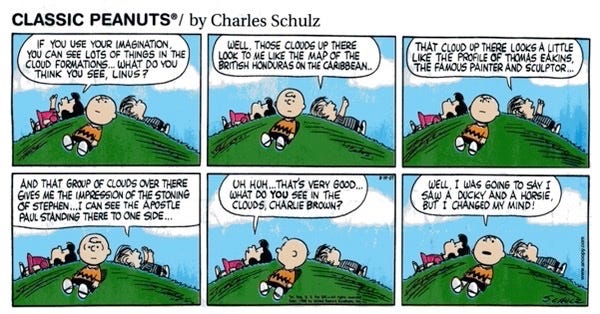

It is a deeply human characteristic to perceive order in chaos. We see faces in household appliances and farm animals in the clouds.

We seem particularly susceptible during health crises, which spawn their own pandemic of misinformation.

The AIDS crisis was replete with dangerous falsehoods – including the belief that the HIV virus was created by a government laboratory, the assertion that HIV tests were unreliable, and even the spectacularly unfounded claim that it could be treated with goat’s milk (thanks, Bill Maher). These lies increased risky behavior and exacerbated the crisis.

On our best days, when wearing the right sort of spectacles, squinting and tilting our heads just so, we can be observant, efficient, loyal, focused, assertive truth-tellers. However, on many days, all too much of the time, we’re delusional, lazy, short-sighted, partisan, arrogant, easily distracted confabulators. It’s an unfortunate reality, but reality nonetheless.

We want to think it’s somebody else or just the “other side,” but it’s all of us.

As I explained in my special mid-week “Mail Call” edition of TBL, our allegiances influence how we see the world and what we deem true to a remarkable extent and with numbing regularity. Opposing “teams” view such things as controversial calls by officials, candidate debate performances, and even science through their own partisan lenses. What we want to be true becomes what we think is true shockingly often.

To make a difficult situation worse, the smarter one is, the more susceptible – smart people are better at coming up with clever ways to view the “problem” as not a problem, rationalizing their views, and finding information that seems to support what they thought all along. And, to put a nice bow on it, the ever-increasing universe of data available to us provides more and more opportunity for “seeing things differently.”

Oh, and an astonishing number of us are downright crazy.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes and the author of many great paeans to rationality, believed in fairies and thought his wife could talk to spirits.

George Bernard Shaw was a flat-earther. Mark Ruffalo and Spike Lee are 9.11 truthers. Albert Einstein was so committed to socialism he refused to recognize the failures of the Soviet Union. Alice Walker supports the idea that Jews funded the Holocaust and maybe it didn’t even happen.

Surprising numbers of Americans today believe crazy things: that vaccines cause autism, that the earth is flat, that the moon landing was faked, that President Donald J. Trump was in the thrall of Russian oligarchs or even a Russian agent, that millions of illegal votes were cast in the 2020 election, that Covid or the vaccines to counter it are a hoax, and more.

During the 2004 presidential election cycle, 30 men – half who saw themselves as “strong” Republicans and half as “strong” Democrats – were tasked as part of a research study with assessing statements by each candidate in which the candidates clearly contradicted themselves. Not surprisingly, Republican subjects were as critical of Kerry as Democratic subjects were of Bush, yet both found ways to justify their favored candidate’s statements.

Stephen Stills got the concept by 1966, well before Tversky and Kahneman, when he and Buffalo Springfield first performed his song, “For What It’s Worth.” The words echo still.

What a field day for the heat (Ooh ooh ooh) | A thousand people in the street (Ooh ooh ooh) | Singing songs and they carrying signs (Ooh ooh ooh) | Mostly say, “Hooray for our side” (Ooh ooh ooh)

Ooh ooh ooh.

This week’s TBL is going to consider three heuristics to help us combat our tendency toward conspiracy. If you like The Better Letter, please subscribe, share it, and forward it widely. It’s free, there are no ads, and I never sell or give away email addresses.

Thank you for reading.

For What It’s Worth

I watched the first-ever broadcast of “Saturday Night Live” on October 11, 1975. George Carlin hosted with Janice Ian and Billy Preston as musical guests. Late in the broadcast, a mock commercial was shown featuring future senator Al Franken, presciently, as a caveman, for the “Triple Track,” a three-bladed razor, with “not just two blades in one system [which had debuted in 1971], but three stainless, platinum teflex-coated blades melded together to form on incredible shaving cartridge.” The ad promises to leave men’s faces “as smooth as a billiard ball.”

“Because you’ll believe anything.”

While the statement is widely and wildly true, at least some of the time, it turns out that, in this instance, the SNL folks don’t forecast the future any better than the rest of us. Despite the claim of unbelievability, it wasn’t so very long before three-bladed razors became a real thing./1/ More importantly, our thinking would be greatly improved by employing a “Triple Track” of razors of a different sort.

William of Ockham is best known for the famous slogan known as “Ockham’s Razor,” often expressed as “Don’t multiply entities beyond necessity.” In practical terms, it is a rule of parsimony meaning that other things being equal, simpler theories are better.

As Einstein said, “more complicated systems and their combinations should be considered only if there exist physical-empirical reasons to do so.” Newton’s iteration was, “We are to admit no more causes of natural things than such as are both true and sufficient to explain their appearances.” As Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes expressed it (remember the irony – Doyle believed in fairies), in reverse (and often copied), “If you eliminate the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.”

Hanlon’s Razor is another related and useful heuristic which can be best summarized as, “Never attribute to malice that which can be adequately explained by neglect, incompetence, or stupidity.” And don’t forget randomness. As Hume noted, we are much too eager to ascribe malice (and goodwill) to natural objects and phenomena.

Our third razor is a much newer one. As the great Charlie Munger said, “more damage to the world comes from the cognitive glitches than does from malevolence.” In other words, “it’s not you, it’s me.” As I’ve dubbed this “Munger’s Razor,” we now have three helpful, good, and related “razors” to aid our thinking. They aren’t ironclad rules, but they are effective rules of thumb – heuristics to guide our thinking.

Looking at conspiracy theorists illustrates the power of such heuristics nicely. A conspiracy theory is a purported explanation for an event that invokes a conspiracy by powerful actors when other explanations are much more probable, held onto tenaciously, irrespective of evidence.

Whether it’s the conviction that the Apollo moon landing was faked, 9/11 was an inside job, vaccinations cause autism, climate change is a Chinese-invented hoax, President Trump was in the thrall of Russian oligarchs or even a Russian agent, millions of illegal votes were cast in the 2020 election, Covid or the vaccines to counter it are a hoax, or something else (“They’re turning the freaking frogs gay!” Alex Jones famously screamed), conspiracy theories all invoke highly complex explanations for events better and more simply explained in other ways./2/

There are good, practical reasons for refusing to fall for every alleged conspiracy. Watergate has been the biggest conspiracy in my lifetime. It was undertaken by a small group of the most powerful men in the world with enormous incentives to keep their actions secret. That they failed, quickly and comprehensively, provides strong evidence that conspiracies are exceedingly hard to maintain.

One prominent “cognitive glitch” that empowers conspiracy theories is our inherent overconfidence, even as our conspiracy theories are often totally bizarre and getting more far-fetched all the time.

“Nothing is so common-place as to wish to be remarkable,” as Oliver Wendell Holmes (Senior) put it.

Conspiracy theorists see themselves as having privileged access to special knowledge or a special way of thinking that separates them from the unfortunate masses. Conspiracists — pretty much every last lost one of us about something or other — love to see themselves as having a “very particular set of skills” allowing them to see things and understand things others cannot.

We tend to think that our own refuse smells delightful and that those who disagree with us aren’t merely wrong, but are rather some combination of delusional, stupid, or evil. Thus, discussions turn into nasty arguments, disagreements turn into ideological scrums, and serious disputes become white-hot with rage, invective and ad hominem (basically Twitter’s raison d’être).

Nobody should doubt that social media prioritizes engagement – clicks, likes, replies, and shares – over truth.

My sense is that the key element here is that most partisans see “their side” as not just true, but obviously true. It’s a by-product of our inherent self-aggrandizement and bias blindness. Therefore, our strongly held positions aren’t truly debatable — they’re seen as objectively and obviously true. After all, if we didn’t think our positions were true, we wouldn’t hold them. And (our thinking goes), since they are objectively true, anyone who makes the effort to try should be able to ascertain that truth.

Our opponents are thus without excuse – they’re stupid, delusional, or evil. If they disagree with me, they are denying reality. Our highly polarized society, fueled by digital and social media (which serve as “crack for moralists,” in Alan Jacobs’s telling phrase/3/), is ever more committed to seeing our opponents in this unflattering and dangerous light. The “triple track” of razors outlined herein offer a means of doing and being better.

For what it’s worth, a 2014 study suggests that being primed to think analytically rather than intuitively could reduce belief in conspiracy theories. So here is your primer – may it be so – and three questions for practice.

Emily introduces you to her two sisters, April and May. What do you think the name of the other sister is?

You’re running in a race, and you pass the runner in second place. What place are you in?

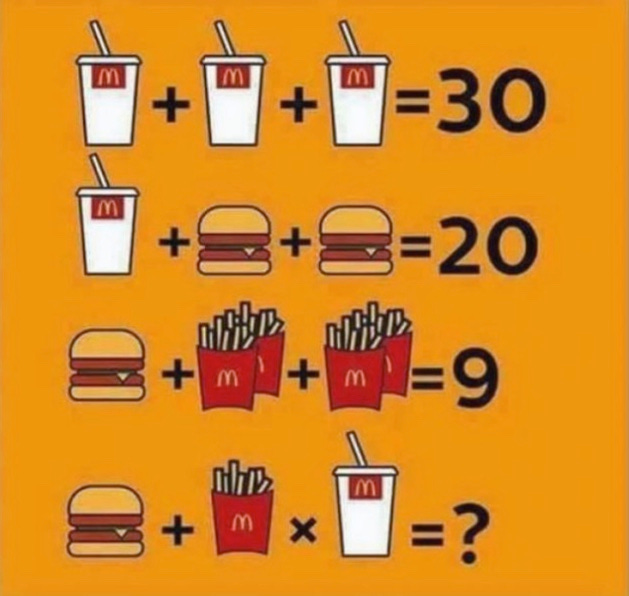

What is the answer to the problem below?

The first two questions have intuitive – wrong – answers (June and first place) and analytical – correct – answers (Emily and second place). The third question is sneaky. We tend to think we’ve “gotten it” if we do the algebra correctly, note that there are *four* sleeves of fries in the third row, and see the multiplication sign in the fourth row. It’s easy to miss the embedded order of operations issue (the correct answer is 15, right?).

Going with your gut is not a recipe for success. On the other hand, those who take the time to consider the available information and to analyze it critically and carefully will have a much better chance of avoiding falling for some conspiracy.

Sadly, it’s far from a guaranty. Every last lost one of us has a brain that takes shortcuts, makes unwarranted assumptions, and sometimes works in irrational ways.

That’s because we’re all human, for what it’s worth.

______________________

1/ Gillette announced the Mach3 three-bladed razor in 1998. The Schick Quattro four-bladed razor debuted in 2003 and Gillette brought out a five-bladed razor in 2005. Dorco’s “Pace 7” razor launched in 2015, and boasts three-and-a-half times the shaving ability of your two-bladed Bic disposable. The jokes today are about 18-bladed razors.

2/ To be clear, conspiracies exist. “Just because you’re paranoid,” Joseph Heller wrote in Catch-22, “doesn’t mean they aren’t after you.” But it should go without saying that we ought not accept conspiracies as fact without very good reasons. Sadly, it can’t go without saying because surprisingly huge numbers of us believe them far too readily.

3/ “When a society rejects the Christian account of who we are, it doesn’t become less moralistic but far more so, because it retains an inchoate sense of justice but has no means of offering and receiving forgiveness. The great moral crisis of our time is … vindictiveness. Social media serve as crack for moralists: there’s no high like the high you get from punishing malefactors. But like every addiction, this one suffers from the inexorable law of diminishing returns. The mania for punishment will therefore get worse before it gets better.”

Totally Worth It

Please send me your nominees for this space to rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or via Twitter (@rpseawright).

Monday’s special mid-week “Mail Call” edition of TBL included a 9.11 Memorial Edition of Totally Worth It. If you haven’t already, I encourage you to have a look.

This is the best thing I saw or read this week. The most important. The most fascinating. The most despicable. The most troubling. The sanest. The most hypocritical. The most real. The funniest. The cutest. Burying the lede. Ben Hogan teaches behavioral finance.

RIP, Norm MacDonald.

Feel free to contact me via rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or on Twitter (@rpseawright) and let me know what you like, what you don’t like, what you’d like to see changed, and what you’d add. Don’t forget to subscribe and share.

Of course, the easiest way to share TBL is simply to forward it to a few dozen of your closest friends.

Benediction

This week’s benediction is from Michael Ebenezer Kwadjo Omari Owuo, Jr., the Grime rapper known in the music world as Stormzy. He is supported here by Ed Sheeran and Aion Clarke. The song begins at about the 1:45 mark.

Thanks for reading.

Issue 80 (September 17, 2021)