The Better Letter: Believing is Seeing

The lessons we’re most likely to learn are those we already know.

Let’s get right to it.

Believing is Seeing

My daughter’s husband is in the military and he has been away on assignment for several weeks this spring. She and their three delightful children spent a good bit of that time with us.

Their oldest, Will, is seven and a full-on baseball fanatic. He loves to play it, to watch it, to talk about it, to read about it, and to collect the cards. I heard, “Let’s play catch, Grandbob,” a lot. Naturally, he wanted to go to a Padres game while he was here and, just as naturally, we obliged.

It’s all about indoctrinating the next generation.

Because of bedtimes, we needed an afternoon game and there was only one at Petco Park while they were with us. It was against the Cardinals and was the ESPN Sunday Night Baseball game of the week (a 4:00 p.m. start here).

The problem was that Will’s (terrific) dad is from Missouri and loves the Cardinals. So, Will was torn. He wore Padres gear to the game and said he was cheering for both teams. But he’s loyal to his dad and the Cardinals.

That’s as it should be. And his tribal rooting interest was never far from the surface.

In the top of the first inning, with two out, runners on second and third, and St. Louis already up 2-0, Harrison Bader hit a rocket to center field. The rally was snuffed out by Padres center fielder Trent Grisham.

Will was adamant that Grisham trapped the ball. Together, we watched the slow-motion replay – the same replay shown in the video above – on the big screen in the ballpark. He was still seeing with his heart. “He trapped it,” Will shrieked.

For Will, as with humans generally, believing was seeing rather than the other way around.

As I like to say, we tend to think we are like judges, carefully weighing the available evidence to adduce the best possible approximation of reality. Truth is, we’re much more like lawyers, scrounging for any plausible basis for confirming our priors.

Confirmation is common – routine. We generally see what we want to see, accept these desires as truth, and act accordingly. Confirmation bias is as natural to us as thinking about starting that diet right after this piece of cake.

Will wasn’t alone, of course.

In the fourth inning, Manny Machado reached base on a throwing error by Cardinals third baseman Nolan Arenado. The next pitch resulted in a ground ball to second baseman Tommy Edman.

Edman gloved the ball, moved into Machado’s path, and ostensibly tagged him for the out. He was unable, however, to throw to first for a double play because Manny dropped into a feet-first slide, upending Edman. Instead of two outs and nobody on, there was only one with a runner on first.

The Padres went on to score twice, tying the game, before Cardinals pitcher Kwang Hyun Kim recorded another out. The Pads scored twice more before the inning was over and took the lead for good.

After Manny’s slide, Twitter went nuts. Twitter denizens – mostly Dodgers fans, apparently – thought the play was dirty and that Machado should have been called out for interference.

As so often happens, the Twitter “experts” were clearly and obviously wrong. Machado had a right to the basepath and he did not interfere with Edman’s right-of-way to field the batted ball. Manny’s exact response is routinely taught throughout the Major Leagues. As former manager and current MLB analyst Buck Showalter said, “It’s a great, thinking man’s baseball play.”

When we grab a glass of what we think is apple juice, only to take a sip and discover that it’s actually ginger ale, we react with disgust, even when we love the soda. We quite naturally try to jam the facts into our preconceived notions and commitments or simply miscomprehend reality such that we accept a view, no matter how implausible, that sees a different set of alleged facts, “facts” that are used to support what we already believe – such as “Manny Machado is a dirty player” or “I want the Padres to lose.”

It isn’t just “somebody else” with the problem, either.

Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman spent 500 pages demonstrating that “it is easier to recognize other people’s mistakes than our own.” For example, in 1951, Bertrand Russell offered a paean to liberalism and the idea that the calm search for truth remains the hope of humanity. It is excellent overall, yet unironically offered “Ten Commandments that, as a teacher, I should wish to promulgate,” including this one: “Have no respect for the authority of others, for there are always contrary authorities to be found.”

It may be easy to see that Republicans are crazy to pretend that November’s election was somehow stolen, the January 6 insurrection was like a normal tourist visit to the Capitol, or former President Trump had no dangerous or inappropriate role in it. It may not be so easy to see the crazy in deciding that huge, in-person BLM protests are actually okay during a pandemic, a three-time Jeopardy winner holding up three fingers for three wins should be canceled as a white supremacist, or lockdowns, school closures, and outdoor mask-wearing are necessary after vaccination.

Maybe it’s the other way around for you, depending on your politics. Or something else entirely.

Instead of finding and exposing the truth, too much modern media consists of trying to mediate the truth in an effort to control or, at least, manage an American public deemed unruly, backward, and insufficiently discerning.

The list of things – really important and seemingly well-established and researched things – that the collective “we” have been wrong about is a long one. For example, we thought that ulcers were caused by stress until Barry Marshall and Robin Warren showed that the bacteria H. pylori is the actual cause (and won a Nobel Prize for doing so). We were also sure of the existence of ether, the medium through which light was thought to travel, throughout the universe. The celebrated Michelson-Morley experiment provided hard evidence that ether did not exist.

As Oxford’s Teppo Felin presciently pointed out, “what people are looking for – rather than what people are merely looking at – determines what is obvious.”

On Saturday, “rad-trad” Sohrab Ahmari, also op-ed editor of The New York Post, claimed that Amazon was “shadow-banning” his new book because it wasn’t showing up in Amazon search results. That wasn’t an entirely crazy notion in that Amazon has done exactly that to certain books with a conservative spin. Even after Amazon confirmed that it was a technological glitch and then fixed the problem, the rad-trads weren’t satisfied. As Notre Dame’s Patrick Deneen claimed, if Amazon “weren’t canceling author’s books, everyone would have assumed it was a technical glitch. Who can trust any such claim now?”

Fortunately, nobody in this imbroglio needed to trust anybody else. Instead of leaning into their innate confirmation bias and looking for examples to confirm the alleged banning narrative, the aggrieved needed only to look for disconfirming evidence – to find what they weren’t looking for.

There was plenty.

Most significantly, lots of books were similarly “canceled” that didn’t fit the Ahmari narrative, including books on the video game industry and by such conservative firebrands as Barack Obama, Jake Tapper, and Ta-Nehisi Coates. Meanwhile, the progressive news site Mondoweiss recognized the same glitch but applied their favored narrative to conclude Amazon was silencing Palestinian voices. Readers were ominously asked to provide examples and, sure enough, that narrative was seemingly confirmed, too.

This is a classic example of the usefulness of Hanlon’s Razor, a rule of thumb that one should never attribute to conspiracy or malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity. Amazon’s technological failure was seen as a politically motivated cancellation because of course it was. That said, an Amazon banning is probably good for sales and cable news hits. So there’s that.

Hanlon’s Razor works because of the problem of induction. Science never fully proves anything. It analyzes the available data and, when the force of the data is strong enough, it makes only tentative conclusions. These conclusions are always subject to modification or even outright rejection based upon further evidence gathering. The great value of data is not so much that it points toward the correct conclusion (even though it often does), but that it provides opportunities to show that some things are conclusively wrong. Never seeing a black swan among a million swans seen does not prove that all swans are white. However, seeing a single black swan conclusively demonstrates that not all swans are white (see here for a particularly interesting example).

As in the Amazon example above, when looking at a proposed hypothesis, such as “Amazon is shadow-banning my book,” we should be spending much more of our time focused upon a search for disconfirming evidence. The great Charlie Munger famously said, “If you can get good at destroying your own wrong ideas, that is a great gift.” But we don’t do that very often or well, as illustrated by a variation of the Wason selection task, shown below. Note that the test subjects were told that each of the cards has a letter on one side and a number on the other.

Most people give answer “A” — E and 4 — but that’s wrong. For the posited statement to be true, the E-card must have an even number on the other side of it and the 7-card must have a consonant on the other side. It doesn’t matter what’s on the other side of the 4-card. But, we turn the 4-card over because of our confirmation bias. We intuitively want confirming evidence. We don’t think to turn over the 7-card because we tend not to look for disconfirming evidence. In a wide variety of test environments, fewer than 10 percent of people get the right answer to this type of question.

We like to think that we see the world as it truly is. The difficult and dangerous reality is that we tend to see the world as we truly are. As C.S. Lewis wrote in The Magician’s Nephew, a children’s book that is so much more than that, “What you see and what you hear depends a great deal on where you are standing. It also depends on what sort of person you are.”

When we are confronted with evidence that disconfirms our beliefs, we do not become more open-minded as Bayesianism predicts, but rather become more dogmatic. We see confirming evidence and ask if it can be true. With disconfirming evidence, we ask if it must be true. Because of confirmation bias, the lessons we’re most likely to learn are those we already know.

We all recognize – at least theoretically – that we’re wrong a lot. We just can’t come up with current examples. For all of us, far too often, believing is seeing.

Dear Harv

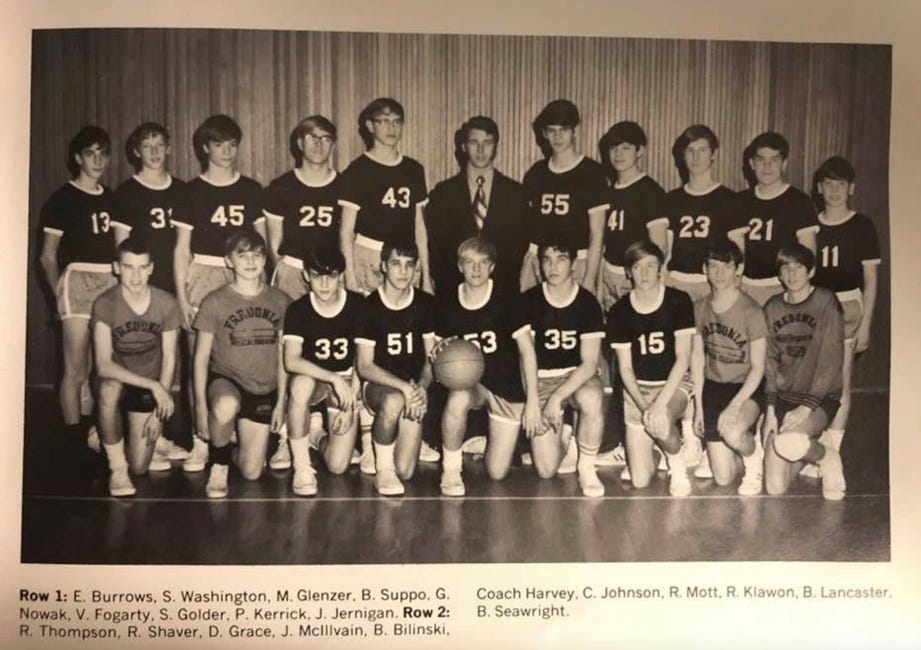

While I was walking on the beach last weekend with my lovely bride, our daughter, and her children, I got a text from a high school friend that our ninth-grade basketball coach has stage four esophageal cancer and is about to start radiation and chemo. He was the cool math teacher in our high school (he had us call him “Harv”), but I was never cool enough to be in any of his classes. His daughter asked for remembrances from former students. Here’s mine.

Dear Harv –

Ninth grade isn’t often great for anybody and it was especially iffy for me. I was (and am) an introvert. I was in classes with very few kids I had gone to school with up to that point. I had a high voice and not even a hint of facial hair. I was more than fourteen inches shorter than I eventually became.

I didn’t have a lot to work with.

After basketball season started, the friends I did have and I used to go watch you light it up in adult league hoops. We were convinced we were analytically ahead of our time and decided you could perhaps have played in the ABA – constrained by your lack of height but buttressed by some amazing outside shooting, because the ABA was the only professional league at the time with a three-point shot. To us, you may not have been tall, but you were bigger than life.

In a year I have largely and willingly forgotten, you provided my single finest moment. I doubt you remember it. In fact, I’m certain you don’t. Since my much better half is a teacher, I’m well aware that students remember far more about their teachers than vice versa. The numbers demand as much.

I’m also aware that, for good practitioners, teaching isn’t just a job, a vocation, or a profession. It’s a calling, if not necessarily a religious one. Nobody does it for money or prestige.

Frederick Buechner, novelist and preacher, described it like this: “The place God calls you to is the place where your deep gladness and the world’s deep hunger meet.”

Ninth grade me was hungry for affirmation in a world where I didn’t feel like I counted. You provided it. It wasn’t big or splashy. But it mattered. It still matters.

One day after practice, you put your hand on my shoulder, looked me in the eye, and told me that I’d be starting for you in the upcoming season opener. I was, of course, delighted.

When I went to Duke, I was friends with basketball players and ran with them a fair amount. Later, as an adult, I played with and against several former NBA players. As an adult, I coached some excellent basketball teams, youth through high school, and players who went on to some remarkable things in the sport, including a Final Four. I don’t mean to suggest that I was ever anything like a great player or coach, or even a good one (I wasn’t), but I mention these things to provide some context for my telling you that nothing I ever did on the basketball court meant nearly as much as what you said to me that December afternoon.

Disease has a way of focusing our attention on what matters and how we want to be remembered. I’d like to be remembered for how well I lived my life in moments big and small. Who we really are is often best revealed in small moments without an audience.

Like that cold winter day in western New York.

Elsewhere, Buechner suggests that we should “listen” to our lives. That means we should “[s]ee it for the fathomless mystery it is. In the boredom and pain of it, no less than in the excitement and gladness: touch, taste, smell your way to the holy and hidden heart of it, because in the last analysis all moments are key moments, and life itself is grace.”

That day in the gym, you saw me for what I could do more than for what I couldn’t, what I might become more than who I was.

It was a throw-away conversation in the overall scheme of things. But, to me, it was a key moment of affirming grace. I am most grateful for it.

Thank you, Harv.

Totally Worth It

I love musical mash-ups. The best of them combine individually great songs that, when combined, sound MFEO.

Here’s one. It includes songs from Hamilton and Dear Evan Hansen and features the original Broadway stars of each. It’s about longing to matter and be remembered.

This is the week’s best thing I saw or read. The most significant. The most spot-on. The oddest. The most provocative. The most out there. The most amazing. The most sensible. The most devastating. The meanest (but with a better ending). The most mysterious. The coolest.

Please contact me via rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or on Twitter (@rpseawright) and let me know what you like, what you don’t like, what you’d like to see changed, and what you’d add. Don’t forget to subscribe and share.

Of course, the easiest way to share TBL is simply to forward this email to a few dozen of your closest friends.

Here’s a terrific new love song from NEEDTOBREATHE, featuring Carrie Underwood, about remembering.

Benediction

Christopher Foley, the bassist of the indie punk rock band of devoted Christians, Luxury (the subject of a fascinating new documentary), and an Orthodox priest, described how his vocation as a priest helped him understand what the band does. It’s this week’s benediction.

“What does a priest do? A priest is one who … offers something up that then gets returned to us as something life-giving. We don’t take wheat and grapes; we take bread and wine, the work of man’s hands. And that’s what’s lifted up unto Christ, and that’s what gets returned to us as Christ himself, as something life-giving.

“The question isn’t ‘Are you a Christian band or not?’ It’s just, ‘Are you, by nature of your life vocation, a priest of creation who offers up … everything that is your matter, you know, your stuff of life — are you taking it and offering it up? And then if you’re offering it up, are you receiving it as something life-giving?’”

May the answer, for all of us, be “Yes and amen.”

Thanks for reading.

Issue 64 (May 21, 2021)