My San Diego Padres, over the past two weeks, have dropped from first place overall in a variety of power rankings to third place in their division, dramatically lowering their chances of winning the National League West. Despite last night’s dramatic walk-off win, FanGraphs now gives them just an 18.2 percent chance of winning their division. The Padres have lost 13 of their past 18 games and have failed to win any of their past five series. Manny Machado, Eric Hosmer, and Wil Myers, the Pads’ three highest-salaried position players, mashed last season but have slogged so far this year. “I do know that right now we’ve got to weather the storm we’re in,” manager Jayce Tingler said this week. “You have to embrace, in this game, the struggles and challenges.”

Baseball is insanely frustrating, in large part because it is so hard (“struggles and challenges”).

Source: The New Yorker

Of course, “[i]t’s supposed to be hard. If it wasn’t hard, everyone would do it. The hard is what makes it great.”

The hard is also why it offers so many important lessons.

A few of those lessons are the subject of this week’s TBL. If you like The Better Letter, please subscribe, share it, and forward it widely. It’s free, there are no ads, and I never share email addresses.

Thanks for reading.

Get a Good Pitch to Hit

Ted Williams was almost surely the greatest hitter of all time. He was a two-time MVP, led the league in hitting six times, in home runs four times, and won the Triple Crown twice. A 19-time All-Star, he had a career batting average of .344 with 521 home runs and was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1966.

Williams was also the last player in Major League Baseball to hit over .400 in a single season: .406 in 1941. Ted’s career was twice interrupted by service as a U.S. Marine Corps fighter-bomber pilot. He served in World War II (1942-1946) and the Korean War (1952-53). Had his career not been limited by his military service, especially since it was in his prime, Williams’ achievements would surely have been even more incredible. He likely would have hit over 700 career home runs and challenged Babe Ruth’s record.

During spring training of his first professional season, Williams met Rogers Hornsby, who had hit over .400 three times and who was a coach for his AA team for the spring. Hornsby emphasized that Ted should always “get a good pitch to hit.” That concept became Williams’ “first rule of hitting” and the key to his famous and innovative hitting chart (shown below).

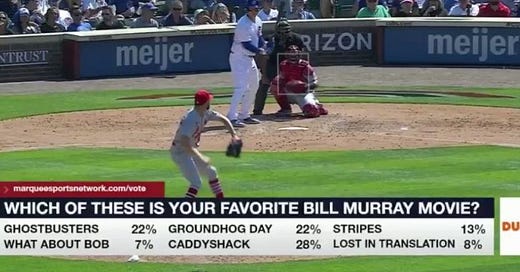

The concept is a straightforward one — it’s easier to hit a pitch that’s belt high and right down the middle than one at the knees and “on the black.” Watch this magnificent 14-pitch at-bat by Anthony Rizzo of the Cubs from earlier this week (and the answer to the quiz is “Groundhog Day”).

Rizzo keeps fouling off tough, borderline pitches before finally getting a good pitch to hit – a fastball right down Broadway, in the sweet spot of the Williams chart – and hits a bomb into the right-field bleachers.

In part, getting a good pitch to hit means being analytically aware and thus seeking out approaches and strategies that offer a good likelihood of success. It means being selective about our choices and our opportunities.

Value – in baseball, in life, and in my day job, investing – surely exists, but it can be vanishingly hard to find. I generally recommend starting by being very selective — getting a good pitch to hit. Every opportunity isn’t a good opportunity. When you don’t have a good pitch to hit, don’t swing or, if it’s a tough strike, try to fight it off. When you do get a good pitch to hit, hack away.

Get Ahead in the Count

For both pitcher and hitter, getting ahead in the count pays big dividends. For example, batters on 1-0 counts produce lines roughly 13 percent better than their overall numbers in those plate appearances. On 0-1 counts, batters do roughly 16 percent worse. The whole grid looks like the following.

Source: FanGraphs

The lessons are obvious. Pitchers should throw more strikes and hitters should swing at strikes. More broadly, don’t make things harder for yourself, don’t waste opportunities, and when you have a good opportunity, jump on it.

Find Value

Moneyball focused on the 2002 season of the Oakland Athletics, a team with one of the smallest budgets in baseball. At the time, the A’s had lost three of their star players to free agency because they couldn’t afford to keep them. A’s General Manager Billy Beane, armed with reams of performance and other statistical data, his interpretation of which was rejected by “traditional baseball men” (and, not coincidentally, also armed with three terrific young starting pitchers as well as the fine shortstop, Miguel Tejada), assembled a team of seemingly undesirable players on the cheap that proceeded to win 103 games and the division title.

Unfortunately, much of the analysis of Moneyball from a business perspective has been focused upon the idea of looking for cheap assets and outwitting the opposition in acquiring those assets. The real lesson of Moneyball relates to finding value via underappreciated assets (some assets are cheap for good reason) by way of a disciplined, data-driven process. Instead of looking for players based upon subjective factors (a “five-tool guy,” for example) and who perform well according to traditional statistical measures (like RBIs and batting average, as opposed to on-base percentage and OPS, for example), Beane sought out players that he could obtain cheaply because their actual (statistically verifiable) value was greater than their generally perceived value.

In some cases, the value difference is relatively small. But compounded over a longer-term time horizon, small enhancements make a huge difference. In a financial context, for example, over 25 years, $100,000 at 5 percent, compounded daily, returns $349,004.42, while it returns nearly $100,000 more ($448,113.66) at 6 percent.

We live in a world that doesn’t appreciate value. In the investment community, indexers are convinced that value doesn’t exist or can’t be reliably measured. Most other would-be investors don’t have a good process for analyzing data and are too focused on trading to recognize value when they see it. While proper diversification across investments can mitigate risk and smooth returns within a portfolio, too much portfolio diversification(“protection against ignorance,” in Warren Buffett’s words) requires that value cannot be extracted.

Similarly, behavioral finance shows how difficult it can be for us to be able to ascertain value. Our various foibles and biases make us susceptible to craving the next shiny object that comes into view and our emotions make it hard for us to trade successfully and extremely difficult to invest successfully over the longer term. Recency bias and confirmation bias – to name just two – conspire to inhibit our analysis and subdue investment performance. Investing successfully is really hard.

To expand the idea (perhaps to the point of breaking), we must always resist the urge to trade – even a good trade – when investing makes more sense. While I don’t mean to suggest that a one-off trip to Vegas for a weekend of fun can never be a good idea, too many trips like that can come between you and your goals and can thus be antithetical to a rewarding future.

My ongoing analysis of human nature suggests that we are not just subject to the whims of our emotions. We are also meaning-makers, for whom long-term value (when achieved) can be fulfilling and empowering. It simply (simple, but not easy) requires the process and the discipline to get there. What we really need is not always what we expect or want at the time.

This point is driven home in a different sort of way by a terrific movie: 50/50, written by Will Reiser about his ordeal with cancer. As Sean Burns noted in Philadelphia Weekly, Reiser’s best friend was the kind of slovenly loudmouth that you’d expect to find played in the movies by Seth Rogen, except that his best friend really was Seth Rogen. Rogen’s fundamental, unexpected decency and supportive love grow more quietly moving as the film progresses.

Rogen was undervalued generally and his love and support provided incalculable value to Reiser.

As the cliché goes, nobody lies on his deathbed wishing he’d spent more time at the office. We appreciate meaning and value more in the sometimes harsh reality of the rear-view mirror than in our mystical (and usually erroneous) projections into an unknown future. When you see good value, grab it. When you have it, hold onto it.

Humility is Required

Everything about baseball demands humility. Great teams lose 40 percent of the time. Excellent hitters fail seven of ten times. Reggie Jackson struck out 2,597 times. Bob Gibson was the losing pitcher 174 times. Aaron Judge struck out in 37 consecutive games and struck out all five at-bats in the same game, twice. My Padres won 14 games in a row in 1999 and finished 14 games under .500.

Baseball is indomitable.

Humility is valuable in life, too. We need personal humility, epistemic humility, and scientific humility. We ought to be humble before God and others.

Hume was suspicious of humility as a “monkish virtue.” However, Augustine insisted that “almost the whole of Christian teaching is humility” and Aquinas taught that humility is the beginning of Christian virtue because without humility we cannot be in a position of openness to truth. Even Kant recognized that humility matters because it reminds us that we are equal with everyone else insofar as we all fall drastically short of the ideal.

Watching attentively to human beings interact (or spending just 10 minutes on Twitter) demonstrates our overarching overconfidence, conceit, and self-centeredness. Nearly all of us overrate our own capacities and exaggerate our ability to shape the future [insert discussion of Friedrich Hayek’s warnings about the folly of planning here].

If we want to have a decent chance of overcoming those obstacles, we need to start with some humility. Just like baseball.

Totally Worth It

Last week, I included a remarkable “golden buzzer” performance of an original song by Jane Marczweski, who goes by the stage name “Nightbirde,” from America’s Got Talent. She’s a young Christian woman facing a horrible cancer diagnosis that promises to extinguish her life far, far too soon. Please consider the searing, honest, and powerful words she offered while struggling in her pain.

“I see mercy in the dusty sunlight that outlines the trees, in my mother’s crooked hands, in the blanket my friend left for me, in the harmony of the wind chimes. It’s not the mercy that I asked for, but it is mercy nonetheless. And I learn a new prayer: thank you. It’s a prayer I don’t mean yet, but will repeat until I do.

“Call me cursed, call me lost, call me scorned. But that’s not all. Call me chosen, blessed, sought-after. Call me the one who God whispers his secrets to. I am the one whose belly is filled with loaves of mercy that were hidden for me.

“Even on days when I’m not so sick, sometimes I go lay on the mat in the afternoon light to listen for Him. I know it sounds crazy, and I can’t really explain it, but God is in there — even now. I have heard it said that some people can’t see God because they won’t look low enough, and it’s true. Look lower. God is on the bathroom floor.”

Please contact me via rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or on Twitter (@rpseawright) and let me know what you like, what you don’t like, what you’d like to see changed, and what you’d add. Don’t forget to subscribe and share.

Of course, the easiest way to share TBL is simply to forward this email to a few dozen of your closest friends.

This profile of Marilynne Robinson, my nominee for best living writer, is excellent: “It seems to me much of what is said today is shallow and empty and false. I believe in the origins of things, reading primary texts themselves — reading the things many people pretend to have read, or don’t even think need to be read because we all supposedly know what they say.”

Despite contenders from the likes of Springsteen, Simon, Sister Wynona Carr, and the Strokes, here is the best baseball song ever.

Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, known for novels like Americanah and for mentoring of young African writers, set the internet ablaze Tuesday when she published an essay in which she described watching a former student spend months slandering her online. Adichie spins what might be a literary gossip story into a treatise on the evils of an internet culture that encourages the signaling of virtue above virtue itself, rewards notoriety at any cost, and allows some to believe that there is no vice in service of the right ideology. “In a deluded way, you will convince yourself that your hypocritical, self-regarding, compassion-free behavior is in fact principled feminism. It isn’t. You will wrap your mediocre malice in the false gauziness of ideological purity. But it’s still malice.”

This is the best thing I saw or read this week; I hope it is an immense success. The most insane. The most disappointing. The most terrifying. The most delightful. The most impressive. The most incredible. Both the most bizarre and the most predictable. The most disgusting. The most inspiring. The most insightful. The most remarkable. The most touching. The funniest. The most worrisome. The best advice. RIP, Beverly Cleary. Wow. TV needs more of this. He should have gone to Nineveh.

My darling bride and I celebrated our 42nd wedding anniversary this week. Depending on your outlook, I am immensely blessed or insanely lucky. Probably both.

Benediction

A reader from Mississippi shared the following from a new artist to me. He’s Paul Thorn, a remarkable singer-songwriter from Tupelo, whose father is a Pentecostal preacher and whose uncle is a pimp. For reals. As I have learned, much spirituality comes through his songs, and this one is entitled, “You Might Be Wrong.” It’s a good anthem for our troubled times.

“Why do we argue? Why do we fight? | Everybody thinks God's on their side. | Just count to ten before you throw a stone. | Whatever you believe, you might be wrong.”

It also makes a fine benediction.

Thanks for reading.

Issue 67 (June 18, 2021)