“Beliefs are like possessions,” Robert Abelson wrote. And how right he was.

This week’s TBL considers the nature of beliefs generally before providing at a “working draft” of my investment beliefs.

If you like The Better Letter, please subscribe, share it, and forward it widely. Please.

NOTE: Some email services may truncate TBL. If so, or if you’d prefer, you can read it all here. If it is clipped, you can also click on “View entire message” and you’ll be able to view the entire post in your email app.

Thanks for visiting.

Investment Beliefs

Facts without interpretation are useless.

We readily recognize that facts are not the same things as truth. Facts are true by definition (or they wouldn’t be facts), but they require analysis, understanding and interpretation to become useful and actionable, to become truth. Logically, we should decide what the facts are as objectively as we can and then interpret those facts to come to a consistent set of beliefs about them.

But that’s not how it usually works.

Usually, we try to jam the facts into our pre-conceived notions and commitments or simply miscomprehend reality such that we accept a view, no matter how implausible, that sees a different set of alleged facts, “facts” that are used (again) to support what we already believe. Since we quite readily see poor thinking in others but fail to see it in ourselves (on account of bias blindness) and live in a highly polarized society wherein commonly accepted facts are increasingly rare, beliefs (at least the beliefs of people who don’t already agree with us) are not generally held in high regard.

I see at least two primary although not necessarily contradictory narratives concerning the nature and utility of belief in the modern world. On the one hand, we see people (always other people) who are hell-bent on claiming that belief (usually manifested ideologically) can and does trump all, that it can deny facts and evidence or simply create its own “alternative facts.” This narrative plays out in religion, politics (right and left), sports, and even investing — everywhere that ideology exists (which is essentially everywhere) — for we are ideological through-and-through. It is also well represented within popular culture.

David Russell’s 2013 film, American Hustle, began as a script by writer and producer Eric Singer entitled, “American Bulls–t.” Who is conning whom? is a constant underlying question, with the major theme expressed by a stripper from the American southwest turned would-be English aristocrat and played by Amy Adams: “The key to people is what they believe and what they want to believe. So I want to believe that we were real.”

Still, truth is irrelevant to “get[ting] over on all these guys” because “people believe what they want to believe.”

The movie is consistent with an ongoing trend in American thought suggesting that beliefs are generally powerful concoctions designed to fool others and ourselves, the province of knaves and charlatans. For example, the great American musical, The Music Man, is a paean to the power of belief.

Personally (but usually only ascertained by others), we tend to test-drive purported beliefs as solutions until we find a set (based on facts or not) that works for us, or until we find one that works better, or reach the limits of our wallets, the law, or common sense.

That last limit is not often reached.

Jesus had a good handle on the problem two millennia ago. “Why do you look at the speck of sawdust in your brother’s eye and pay no attention to the plank in your own eye?”

In a famous 1726 sermon (not an oxymoron), Bishop Joseph Butler asked a penetrating question that we like to think is rhetorical: “Things and actions are what they are, and the consequences of them will be what they will be: why, then, should we desire to be deceived?” The good Bishop, referencing the prophet Balaam, recognized “that strong passions, some kind of brute force within, prevails over the principle of rationality” and that we are all prone to “self-deceit,” to “a peculiar inward dishonesty.” Thus the problem isn’t new and there isn’t any evidence that it’s going away anytime soon, either.

Sadly, evidence suggests that being smarter, more aware, or more educated doesn’t seem to help us to make these sorts of decisions more effectively. Indeed, they may actually make things worse. For example, one study finds that, in many instances, smarter people are more vulnerable to thinking errors, even basic ones. Clever people are able to concoct an approach that makes the desired conclusion seem plausible. Moreover, even “people who were aware of their own biases were not better able to overcome them.”

Expecting people (including ourselves) to be convinced by the facts is contrary to, well, the facts. W. Edwards Deming, perhaps the original data scientist, famously emphasized: “In God we trust; all others must bring data.” But even good data doesn’t necessarily overcome entrenched beliefs. It’s easy for us to see that other people believe all sorts of stupid things but almost impossibly difficult even to consider the possibility what we believe all sorts of stupid things.

Some of us believe in more egregiously stupid stuff than others, of course. As Isaac Asimov (among so many others) has pointed out, there is a cult of ignorance in the United States, and there always has been. The strain of anti-intellectualism has been a constant thread winding its way through our political and cultural life, nurtured by the false notion that democracy means that “my ignorance is just as good as your knowledge.” The idea that beliefs are bulls—t has strong evidential support (if only acknowledged in others).

Where the idea that truth need simply be proclaimed doesn’t work, another narrative suggests that truth may readily and easily be uncovered. Indeed, we eagerly embrace the idea that there is hope for a better process and better outcomes via science and its rigorous method, specifically designed to root out error. This narrative suggests that science is the be-all and end-all of human knowledge and advance. Instead of belief dictating action, it’s science (although it’s deemed no less plug-and-play).

This essay by Steven Pinker provides a helpful example of this narrative in full flower: “the worldview that guides the moral and spiritual values of an educated person today is the worldview given to us by science.” Predictably (thanks to confirmation bias), the worldview Pinker believes that science has uncovered looks quite remarkably like his own.

However, science offers no worldview and no easy answers. It is but a mechanism – a spectacularly successful mechanism to be sure, but a mechanism nonetheless. Pinker disagrees. As he would have it, humanism (the belief in “principles that maximize the flourishing of humans and other sentient beings”) “is inextricable from a scientific understanding of the world.”

How quickly we forget.

Quite obviously, is and ought are quite different things and there is no rational way to derive one from the other. Moreover, the facts simply do not support Pinker’s contention. For example, it was what Engels described as Marx’s “scientific socialism” that gave the world gulags, repression, the Cultural Revolution, Killing Fields, immense poverty, corruption, and scores of millions of horrible and avoidable deaths. To be clear, science was not responsible for these atrocities (evil humans were), but it did not stand in the way either. No mere mechanism, no process can. People committed to science can be just as evil and just as good as anyone else. Science and talented scientists are responsible for both the eradication of small pox and the proliferation of nuclear weaponry.

Progress is not always forward.

Moreover, it should be immediately obvious to even the most casual observer that science — a relatively recent invention — is hardly the only mode of human thought that can be made to work for us. Science, even explaining science, is really hard precisely because the scientific mindset isn’t remotely close to the “natural” mode of human thought.

There is much more to the human experience than measurement and the acquisition of knowledge about physical processes. Moreover, knowing them offers no certain, sure-fire answers. Other ways of thinking have also offered valuable insights into the human condition. Indeed, the American Experiment was founded upon beliefs that cannot be proven or even evidenced very well (if at all), ideals like “all men are created equal,” that “taxation without representation is tyranny,” and that we possess “certain unalienable Rights.”

None of this is to downplay science or the importance of science. It is the best (and perhaps only) means we have to ascertain objective fact. Even so, most of us think of scientific advance as essentially a linear progression. The idea is that science develops by the careful gathering, accumulation, and analysis of evidence such that new truths are built upon old truths (or the increasing approximation of theories to truth), and in only the rare and unusual case, the correction of past errors. This progress might accelerate in the hands of a particularly great scientist, but the ongoing progress itself is thought to be all but guaranteed by the scientific method.

It’s like those multi-initialed television procedurals in which science always saves the day by clearly and unambiguously identifying the killer in the final 15 minutes of the show. Ironically, the real-life evidence doesn’t support this sort of heroic advance. As the great physicist Max Planck wryly noted, science progresses one funeral at a time (much more here).

Scientists routinely acknowledge that they get things wrong, at least in theory, but they also hold fast to the idea that these errors get corrected over time as other scientists try to build upon earlier work. And to a large extent, that’s what happens. However, John Ioannidis of Stanford has shown that, as a matter of statistical logic, “most published research findings are probably false,” and the ongoing replication crisis supports that claim. For example, a study by economists at the Federal Reserve found that less than half of the published papers they examined could be replicated, even when given help from the original authors. A subsequent “meta-meta-analysis” concluded that nearly 80 percent of the reported effects in the empirical economics literature is exaggerated, typically by a factor of two, with one-third inflated by a factor of four or more.

Despite rigorous protocols and a culture designed to promote the aggressive rooting out of error, scientists get things wrong – really important things – a lot more often than we’d like to think.

NARRATOR: “That’s because scientists are as human as the rest of us.”

Side note: The desired incentives (publication; tenure; promotion; prestige; grant money; prizes; etc.) get awarded for findings, the more novel and interesting, the better. They do not get awarded for disconfirmation. Accordingly, and for example, a prominent behavioral scientist has recently been accused of fabricating results in multiple studies, including at least one purporting to show how to elicit honest behavior. As Benjamin Franklin observed in Poor Richard’s Almanack, if you would persuade, appeal to interest rather than reason. We tend to change our minds when our incentives demand it, and not before.

For Pinker, the advocates of evil movements offering at least a veneer of scientific basis are simply not truly Scotsmen scientific. That’s a handy escape route, allowing him to take credit for all the good while avoiding blame for what’s bad, but it’s not remotely credible. While Pinker is right that science is not our enemy, it isn’t necessarily our friend either. Science is an extremely useful and powerful but dangerous tool that must be used carefully and monitored closely.

Facts are inherently stubborn, messy things and often get in the way of our favored preconceived notions, as John Adams famously recognized.

Even scientists fall prey to this tendency. In his famous 1974 Cal Tech commencement address, the great physicist Richard Feynman talked about the scientific method as the best means to achieve progress. Even so, notice his emphasis: “The first principle is that you must not fool yourself – and you are the easiest person to fool.”

Thus, the narrative of constant scientific advance toward readily accessible true beliefs isn’t ultimately compelling either. Happily, however, there is a whole-lot more to the overall story. And an interesting and compelling story it is. Beliefs are dangerous and contentious, but also inherently necessary and potentially of great value.

For example, heroism of any sort involves somebody taking a big risk for a belief. Hitler would not have been defeated without contrary beliefs powerful enough to overcome fear and death. More fundamentally, no matter how committed to data-based reasoning and analysis we are, facts can only take us part-way home. Facts demand analysis to become useful and actionable. The conclusions we reach and the positions we take are ultimately beliefs – beliefs that should be as well-supported by the evidence as possible, of course, but still beliefs.

As noted, we are ideological creatures through-and-through. We consistently prefer stories to data, no matter how fanciful the story or how rigorous the data. It can be maddeningly difficult for us to separate fact from belief. Therefore, it is very dangerous business indeed to lose sight of what works in order to massage our egos, feel comforted, or score ideological points.

Investing is hard enough without trying to foist an ideological overlay to it. As my friend Tom Brakke put it, “[A]s an industry we waste a lot of time borrowing and reinforcing conceptual structures that are already formed rather than trying to shoot holes in them. And most strive too hard to find analogies when anomalies are staring them in the face and going unrecognized or unexamined.” Both markets and ideologies can be unforgiving. We can readily lose at both, but we shouldn’t expect to win at both over the long-term. We should believe in and only focus upon what works.

Even so, like most of us, I think, I desperately want the Truth with a capital-T. I want to follow the instructions and get the desired result. Every. Single. Time. I want to put my money into the machine and get my soda in return. I want to take the puzzle pieces out and have them all fit together perfectly to create a beautiful picture with none left over. I want to take the red pill. I want the Truth.

We so badly want to know “What. It. Is.”

The idea of making decisions in the midst of uncertainty with uncertain outcomes, despite our best efforts, is a terrifying but very real one. As Neo learns in The Matrix, the Truth is a costly and difficult master. Even worse, we don’t have a red pill option. In our world, at least most of the time, truth is small-t truth even when we think we’ve found some. We want deduction but are stuck with induction. We want certainties but are left with no more than probabilities.

Investing, like much of life, combines elements of science and art and is infinitely infuriating and interesting as a result. ESPN’s Zach Lowe, then of the dearly departed Grantland, made this general point in a basketball context.

The interplay between math and team personnel is part of what makes basketball interesting. Math can give you answers that are correct in absolute terms, but the construction of a team plays a role in dictating whether a specific roster can execute those mathematically optimal plans.

We pesky humans readily upset the best-made, logically flawless schemes … if they exist.

In the real world, truth tends to be tentative, provisional, necessarily subject to revision, and thus requiring art to interpret. That’s partly because, again, facts are inherently stubborn and messy things.

We argue about what the facts are and then argue about the interpretation of those facts. Yet the leading modern narratives about the nature and utility of belief (beliefs are a priori and trump all or the right beliefs are readily ascertainable via science) both seem to reject this reality, at least in practice.

I don’t.

Out of this messiness we must cobble together our beliefs (including our investment beliefs) in order to try to create a coherent, meaningful life. I’d love to be able to act upon facts alone, of course, assuming I can come to a fair approximation of them. But facts without interpretation are still useless. Herein I offer my tentative collection of investment beliefs. I’ll no doubt offer other sorts of beliefs in later editions of TBL.

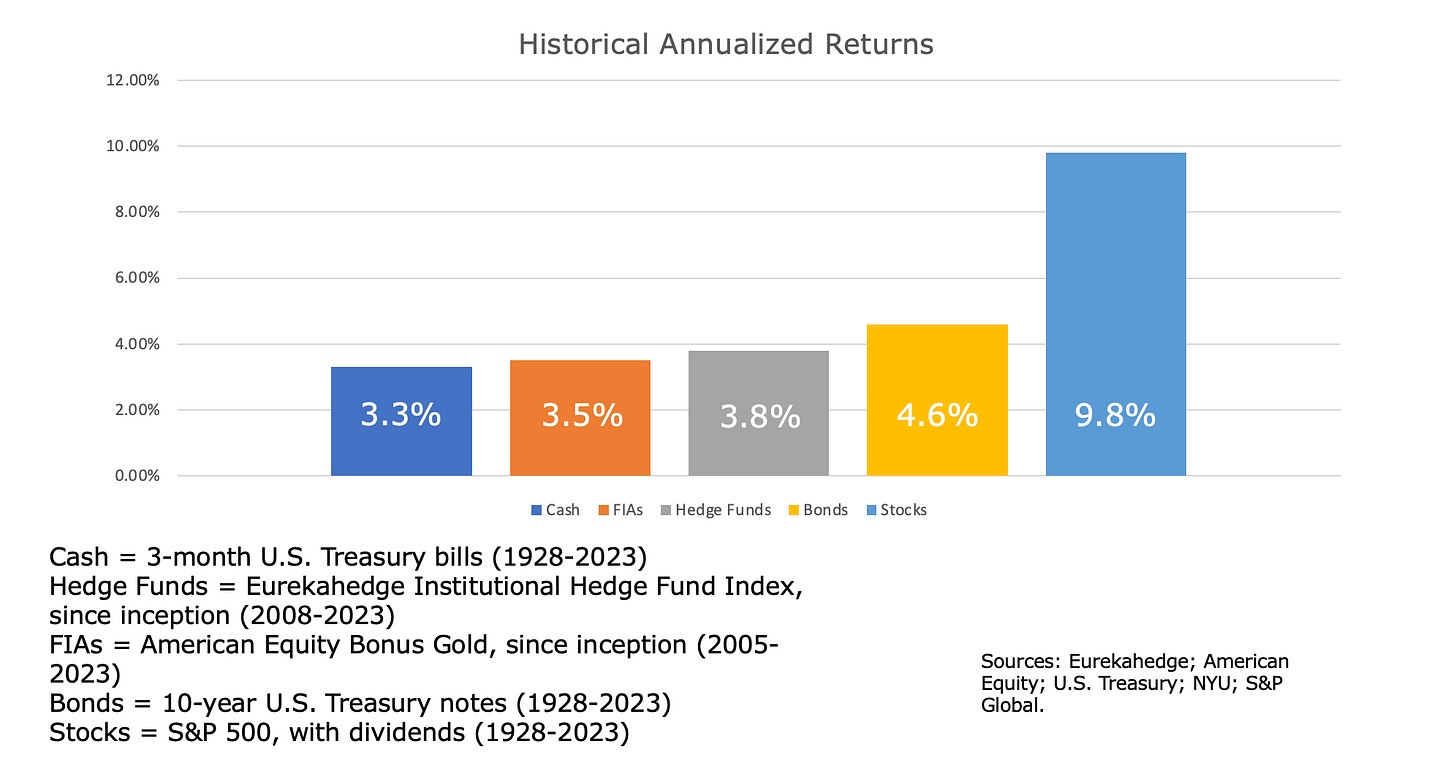

I believe in markets and the power of investing.

I believe in what’s tried and true. What works. Theories and innovations are fine, necessary even. But before one risks his life or her life savings on one or more of them, one would be wise to insist that they be shown — by good evidence and reasons — to work. Evidence-based investing, the sort of investing we should all be doing, is the relentless pursuit of what works, what doesn’t, and why. It’s the way to go.

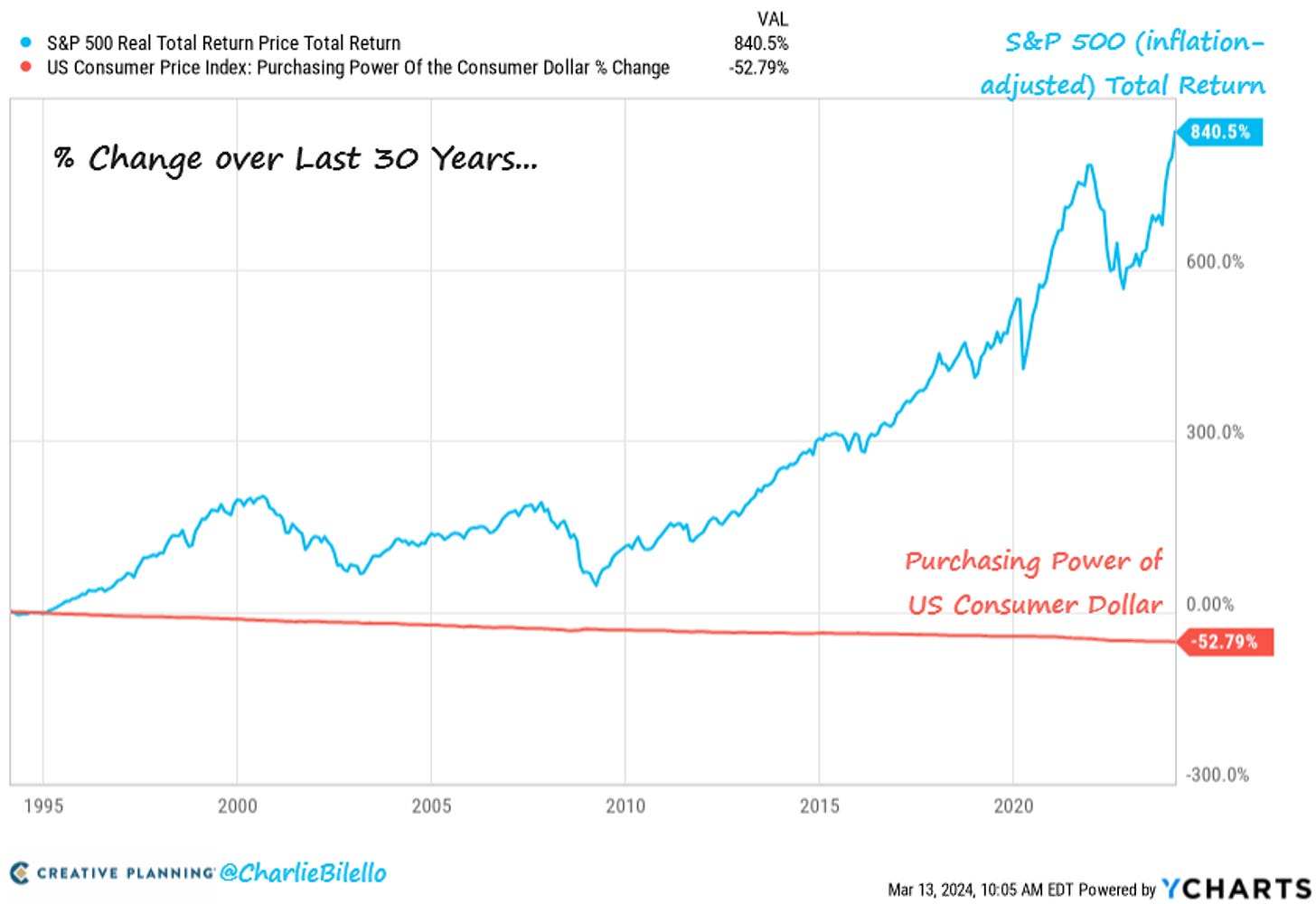

I believe in the importance of investing in stocks.

I believe successful investing without stocks is unlikely.

I believe in the power of compounding (therefore, we should limit friction, such as taxes, costs, and fees).

Although I believe in the power of markets, I also believe that markets are volatile, and need not provide returns on one’s desired schedule.

Even though investing successfully is simple...

...I believe it isn’t easy. That’s because we tend to be our own worst enemy.

I believe managing one’s behavior is more important than managing one’s investments.

I believe good financial health begins with saving. One’s savings rate is much more important that his or her rate of investment returns.

I believe in staying flexible (because the future is not certain, and we are dreadful at predicting it). What works today is not guaranteed to work tomorrow.

I believe in a margin of safety.

I believe the world is more probabilistic than determined. Therefore, I apply probabilistic defaults unless there are good reasons not to in particular instances. Examples include passive investment choices...

...low fees...

...and simplicity.

I believe time is the big edge individual investors have. Therefore, one should focus on the longer-term to the extent possible.

I believe in diversification (because it’s powerful)...

...even though it’s frustrating…

… because diversification works. Concentration, while risky, can create wealth. Diversification protects it.

I believe volatility is the price we pay for longer-term success.

I believe the best time to start investing is as early as possible. Failing that, do it today.

So. What’d I miss?

This is a tentative work in progress. Please let me know what you’d add, subtract, modify, or change.

Totally Worth It

Feel free to contact me via rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or on Twitter (@rpseawright) and let me know what you like, what you don’t like, what you’d like to see changed, and what you’d add. Praise, condemnation, and feedback are always welcome.

Of course, the easiest way to share TBL is simply to forward it to a few dozen of your closest friends.

People pay about $273 a month for subscriptions, which is almost $200 more than they think they pay.

You may hit some paywalls below; most can be overcome here.

This is the best thing I saw or read in the last week. The stupidest. The strongest. The most powerful. The most overdue. The most delightful. Total eclipse. Refuge. Remembering Daniel Kahneman. “One Shining Moment.”

This song has been played a ton this week.

Please send me your nominations for this space to rpseawright [at] gmail [dot] com or via Twitter (@rpseawright).

The TBL Spotify playlist, made up of songs featured here, now includes over 270 songs and about 19 hours of great music. I urge you to listen in, sing along, and turn up the volume.

My ongoing thread/music and meaning project: #SongsThatMove

Benediction

We live on “a hurtling planet,” the poet Rod Jellema informed us, “swung from a thread of light and saved by nothing but grace.” To those of us prone to wander, to those who are broken, to those who flee and fight in fear – which is every last lost one of us – there is a faith that offers grace and hope. And may love have the last word. Now and forever. Amen.

As always, thanks for reading.

Issue 170 (April 12, 2024)

![[Figure 5 – Minimum Necessary Savings Rates Under Isolated and Integrated Approaches] [Figure 5 – Minimum Necessary Savings Rates Under Isolated and Integrated Approaches]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!0J17!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F2d26bf4c-70c9-4c77-aa0b-1c998668fadb_975x559.png)

“Facts without interpretation are useless.”. So very true. Replace “facts” with “data”, the same logic holds true.

I was just reading Jonathan Haidt’s “The righteous mind”, while he did not touch anything about investments, Haidt talked extensively about the human bias and our believe system.